Well, someone on this project didn't carry the one in estimating his free time...

*But it was a way to get the month flying past me.

--Désastre Hurlant: An April Fancy--

I wrote:

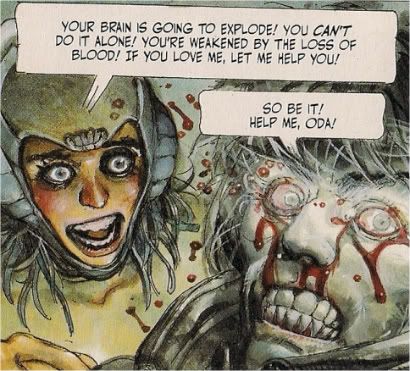

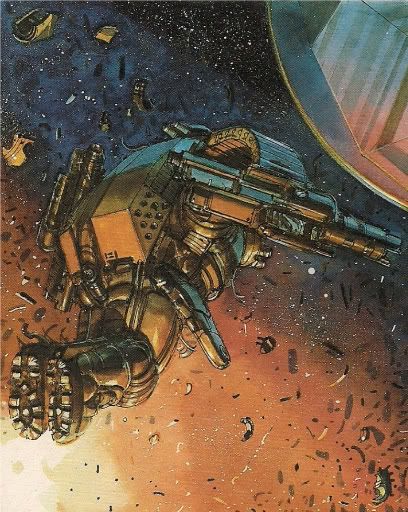

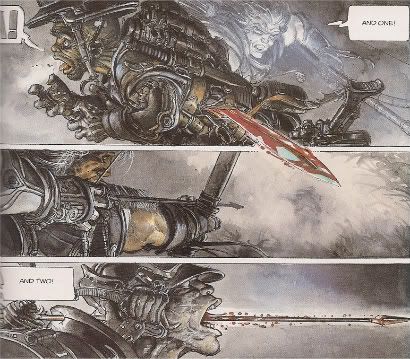

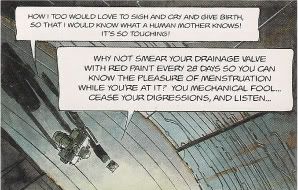

Part 14 (Enki Bilal's Townscapes and The Beast Trilogy: Chapters 1 & 2 - The Dormant Beast/December 32nd)

Tucker wrote:

Part 13 (Bilal's The Nikopol Trilogy)

Part 15 (Mark Malès' Different Ugliness, Different Madness)

Part 17 (Geoff Johns', Kris Grimminger's & Butch Guice's Olympus; funny names for a bunch of French guys)

Naturally, you're wondering "where's Part 16?" Or possibly "when's this fucking thing going to end?" Very simple on both counts: (1) I'm not done writing it, sorry; and (2) when I am done writing it, which will be soon, it'll be the last segment published on this site, leaving only the grand finale of Part 18, a climactic Savage Critics extravaganza in which Tucker and I join forces to lead humankind down the gemstone path into a new age of peace. Coming... with the May!!

*One last batch of new things too -

THIS WEEK IN COMICS!

Angst: The Best of Norwegian Comics Vol. 2: Jesus, Diamond's just getting this through? I bought it at MoCCA 2008. Hmm. Anyhow, this is a $15.00 sampler of works from the nation in the title, a joint publishing effort by Jippi Comics, No Comprendo Press and Dongery Forlag, hell-bent on smacking you around with 128 glossy color and b&w pages of stuff. Lots of variety in style and subject matter - personal favorites include an excerpt from Pushwagner's teeming mark-making metropolis Soft City and a lovely little coming of age thing by Tor Ærlig. Tucker Stone also had some thoughts. Back in June, 2008. Search this out, though!

Second Thoughts: Also in this week's Nordic comics (yeah, that felt like something to type) is an 80-page book from Swedish artist Niklas Asker, a meditation on storytelling wherein fiction and fiction-within-fiction blends around a writer and a photographer and their chance meeting. Lots of shadow and ink; sharp forms. From Top Shelf, a $9.95 softcover perfect for today's troubled world economy. Preview here; way more preview here.

The Collected Doug Wright: Canada's Master Cartoonist Vol. 1 (of 2): The New York Times loves the manga? Bah! Drawn and Quarterly will never rest, and this week it's all-Canada, all-heroes. How about a $39.95 hardcover monster -- 240 pages, 9" x 14" -- devoted wholly to the development of the beloved creator of Nipper? Features art, strips, pictures, letters, journals, a biographical essay by Brad Mackay, an introduction by Lynn Johnston (of For Better or For Worse) and design by Seth. The latter years will follow. Samples.

Path of the Assassin Vol. 15 (of 15): One Who Rules the Dark: And speaking of endings! I think this may be where English-language readers bid their fond farewell to artist Goseki Kojima, at least as far as weathered samurai action goes, beaten as cliffs under waves and sharp like tall grass; Dark Horse has more, newer samurai books from writer Kazuo Koike coming up, but it won't be the same without the late master, no no. Still $9.95 for 304 pages. One last look?

Little Lulu Vol. 19: The Alamo and Other Stories: The Golden Age of Reprints always shines brightest on the 19th volume, or so said Paul to the Romans. Wait... the Alamo? Wasn't that the last volume of Preacher? Ah ha, your ur-text is discovered, Garth Ennis! Collecting another 200 color pages of John Stanley & Irving Tripp delights for $14.95; preview.

Thorgal Vol. 5: Land of Qâ: New from Cinebook (well, new to North America from Cinebook via Diamond), it's another $19.95 collection of two albums from the Jean Van Hamme/Grzegorz Rosiński Eurocomics fantasy mainstay, 1986's The Land of Qâ and The Eyes of Tanatloc (T10, 11), which I think start a big storyline for the titular viking-raised adventure guy. Sample pages here. Note that this week also brings a new edition of vol. 1 in Little, Brown's The Adventures of Tintin series of three-in-one wee hardcovers, but I'm pretty sure it's just a fresh ($18.99) printing of the same Tintin in America, Cigars of the Pharaoh & The Blue Lotus arrangement. TINTIN NEVER WENT TO THE CONGO, FUCK YOU.

Was Superman a Spy?: And Other Comic Book Legends Revealed: Being a 256-page softcover collection/expansion of Comics Should Be Good power master Brian Cronin's popular column, on the case since 2005. Featuring much new material, plus expanded versions of all your favorite excavations of industry lore; congrats to Brian! From Plume, priced at $14.00.

Sherlock Holmes #1: Dynamite may have a lot of comics based on the popular literature of yesteryear, but do they have... mystery? So here are writers Leah Moore & John Reppion and artist Aaron Campbell, and now there's Sherlock Holmes comics out there, which seems right, huh? Look look; $3.50.

Garth Ennis' Battlefields: The Tankies #1 (of 3): Also from Dynamite, a new Ennis-scripted war story, this time following a lost British tank in the struggles following D-Day, and reuniting the writer with his frequent collaborator, Carlos Ezquerra. Gaze. And if your tastes run toward the 2000 A.D. side of the Ezquerra oeuvre, Rebellion should have a new $17.99, 160-page edition of ABC Warriors: The Shadow Warriors, teaming the artist with writer Pat Mills and co-artist Henry Flint.

Phonogram 2: The Singles Club #2 (of 7): Getting back to this full-color, Image-published music-as-magic follow-up from writer Kieron Gillen & artist Jamie McKelvie - each issue is set in the same club, remember. Also remember: two guest artists on back-up stories, Emma Viecelli and Daniel Heard. It's $3.50 for 32 color pages; 'lil look here.

Dark Reign: The Cabal #1: Marvel's got a lot of mini-anthologies or whatnot out this week -- I think the $9.95 Marvel Comics 70th Anniversary Celebration is a 100-or-so-page compendium of beloved plot points and famous pages with a dash of 'full' reprints too, and consider yourself on notice that Marvel Assistant-Sized Spectacular #2 (of 2) features a piece by Adam Warren -- but I think this look at supervillain plans is most worth a peek, if only for the writing crew of Jonathan Hickman, Matt Fraction, Rick Remender, Kieron Gillen and Peter Milligan. Full details and preview here; $3.99 as you like it, etc.

The Muppet Show #2 (of 4): Lots of diverse pamphlets this week; I like a colorful mix. This is the Fozzie issue. From Roger Langridge and Boom! Studios; $2.99. Preview.

Madman Atomic Comics #15: Allred, yes.

RASL #4: Jeff Smith, yes yes, although I've gotta say - that damn pretty oversized collection of the first three issues is gonna be on my mind while flipping through this pamphlet, because that really is the ideal format for this kinda airy action stuff. Still: new Jeff Smith, $3.50. Peep.

Absolute Superman: For Tomorrow: I think I read something about Brian Azzarello recently; there was some stuff on this, the writer's much-maligned 2004-05 take on the Man of Steel with penciller Jim Lee. It did a little for casting the thing as less a calamity of ill-advised assignment than a strange, gloomy, flawed look at the potential for alien detatchment in the Super part of the formula. And if that caught your attention, well... you're still not likely to drop $75.00 on this oversized fancy-pants edition (with a new two-page origin sequence!!!!), but seeing its blocky presence around might prompt you to page through the trades, maybe.

MAD Magazine #500: Yeah, that's something. At the very least, Sergio Aragonés is slated to present his 500 favorite margin drawings as a special feature, so there's a flip right there. I was a little kid in the '80s, the fucking 1980s, and my mom still thought MAD would rot my head if I read it. That's a magazine, man, that's something.

--Désastre Hurlant: An April Fancy--

I wrote:

Part 14 (Enki Bilal's Townscapes and The Beast Trilogy: Chapters 1 & 2 - The Dormant Beast/December 32nd)

Tucker wrote:

Part 13 (Bilal's The Nikopol Trilogy)

Part 15 (Mark Malès' Different Ugliness, Different Madness)

Part 17 (Geoff Johns', Kris Grimminger's & Butch Guice's Olympus; funny names for a bunch of French guys)

Naturally, you're wondering "where's Part 16?" Or possibly "when's this fucking thing going to end?" Very simple on both counts: (1) I'm not done writing it, sorry; and (2) when I am done writing it, which will be soon, it'll be the last segment published on this site, leaving only the grand finale of Part 18, a climactic Savage Critics extravaganza in which Tucker and I join forces to lead humankind down the gemstone path into a new age of peace. Coming... with the May!!

*One last batch of new things too -

THIS WEEK IN COMICS!

Angst: The Best of Norwegian Comics Vol. 2: Jesus, Diamond's just getting this through? I bought it at MoCCA 2008. Hmm. Anyhow, this is a $15.00 sampler of works from the nation in the title, a joint publishing effort by Jippi Comics, No Comprendo Press and Dongery Forlag, hell-bent on smacking you around with 128 glossy color and b&w pages of stuff. Lots of variety in style and subject matter - personal favorites include an excerpt from Pushwagner's teeming mark-making metropolis Soft City and a lovely little coming of age thing by Tor Ærlig. Tucker Stone also had some thoughts. Back in June, 2008. Search this out, though!

Second Thoughts: Also in this week's Nordic comics (yeah, that felt like something to type) is an 80-page book from Swedish artist Niklas Asker, a meditation on storytelling wherein fiction and fiction-within-fiction blends around a writer and a photographer and their chance meeting. Lots of shadow and ink; sharp forms. From Top Shelf, a $9.95 softcover perfect for today's troubled world economy. Preview here; way more preview here.

The Collected Doug Wright: Canada's Master Cartoonist Vol. 1 (of 2): The New York Times loves the manga? Bah! Drawn and Quarterly will never rest, and this week it's all-Canada, all-heroes. How about a $39.95 hardcover monster -- 240 pages, 9" x 14" -- devoted wholly to the development of the beloved creator of Nipper? Features art, strips, pictures, letters, journals, a biographical essay by Brad Mackay, an introduction by Lynn Johnston (of For Better or For Worse) and design by Seth. The latter years will follow. Samples.

Path of the Assassin Vol. 15 (of 15): One Who Rules the Dark: And speaking of endings! I think this may be where English-language readers bid their fond farewell to artist Goseki Kojima, at least as far as weathered samurai action goes, beaten as cliffs under waves and sharp like tall grass; Dark Horse has more, newer samurai books from writer Kazuo Koike coming up, but it won't be the same without the late master, no no. Still $9.95 for 304 pages. One last look?

Little Lulu Vol. 19: The Alamo and Other Stories: The Golden Age of Reprints always shines brightest on the 19th volume, or so said Paul to the Romans. Wait... the Alamo? Wasn't that the last volume of Preacher? Ah ha, your ur-text is discovered, Garth Ennis! Collecting another 200 color pages of John Stanley & Irving Tripp delights for $14.95; preview.

Thorgal Vol. 5: Land of Qâ: New from Cinebook (well, new to North America from Cinebook via Diamond), it's another $19.95 collection of two albums from the Jean Van Hamme/Grzegorz Rosiński Eurocomics fantasy mainstay, 1986's The Land of Qâ and The Eyes of Tanatloc (T10, 11), which I think start a big storyline for the titular viking-raised adventure guy. Sample pages here. Note that this week also brings a new edition of vol. 1 in Little, Brown's The Adventures of Tintin series of three-in-one wee hardcovers, but I'm pretty sure it's just a fresh ($18.99) printing of the same Tintin in America, Cigars of the Pharaoh & The Blue Lotus arrangement. TINTIN NEVER WENT TO THE CONGO, FUCK YOU.

Was Superman a Spy?: And Other Comic Book Legends Revealed: Being a 256-page softcover collection/expansion of Comics Should Be Good power master Brian Cronin's popular column, on the case since 2005. Featuring much new material, plus expanded versions of all your favorite excavations of industry lore; congrats to Brian! From Plume, priced at $14.00.

Sherlock Holmes #1: Dynamite may have a lot of comics based on the popular literature of yesteryear, but do they have... mystery? So here are writers Leah Moore & John Reppion and artist Aaron Campbell, and now there's Sherlock Holmes comics out there, which seems right, huh? Look look; $3.50.

Garth Ennis' Battlefields: The Tankies #1 (of 3): Also from Dynamite, a new Ennis-scripted war story, this time following a lost British tank in the struggles following D-Day, and reuniting the writer with his frequent collaborator, Carlos Ezquerra. Gaze. And if your tastes run toward the 2000 A.D. side of the Ezquerra oeuvre, Rebellion should have a new $17.99, 160-page edition of ABC Warriors: The Shadow Warriors, teaming the artist with writer Pat Mills and co-artist Henry Flint.

Phonogram 2: The Singles Club #2 (of 7): Getting back to this full-color, Image-published music-as-magic follow-up from writer Kieron Gillen & artist Jamie McKelvie - each issue is set in the same club, remember. Also remember: two guest artists on back-up stories, Emma Viecelli and Daniel Heard. It's $3.50 for 32 color pages; 'lil look here.

Dark Reign: The Cabal #1: Marvel's got a lot of mini-anthologies or whatnot out this week -- I think the $9.95 Marvel Comics 70th Anniversary Celebration is a 100-or-so-page compendium of beloved plot points and famous pages with a dash of 'full' reprints too, and consider yourself on notice that Marvel Assistant-Sized Spectacular #2 (of 2) features a piece by Adam Warren -- but I think this look at supervillain plans is most worth a peek, if only for the writing crew of Jonathan Hickman, Matt Fraction, Rick Remender, Kieron Gillen and Peter Milligan. Full details and preview here; $3.99 as you like it, etc.

The Muppet Show #2 (of 4): Lots of diverse pamphlets this week; I like a colorful mix. This is the Fozzie issue. From Roger Langridge and Boom! Studios; $2.99. Preview.

Madman Atomic Comics #15: Allred, yes.

RASL #4: Jeff Smith, yes yes, although I've gotta say - that damn pretty oversized collection of the first three issues is gonna be on my mind while flipping through this pamphlet, because that really is the ideal format for this kinda airy action stuff. Still: new Jeff Smith, $3.50. Peep.

Absolute Superman: For Tomorrow: I think I read something about Brian Azzarello recently; there was some stuff on this, the writer's much-maligned 2004-05 take on the Man of Steel with penciller Jim Lee. It did a little for casting the thing as less a calamity of ill-advised assignment than a strange, gloomy, flawed look at the potential for alien detatchment in the Super part of the formula. And if that caught your attention, well... you're still not likely to drop $75.00 on this oversized fancy-pants edition (with a new two-page origin sequence!!!!), but seeing its blocky presence around might prompt you to page through the trades, maybe.

MAD Magazine #500: Yeah, that's something. At the very least, Sergio Aragonés is slated to present his 500 favorite margin drawings as a special feature, so there's a flip right there. I was a little kid in the '80s, the fucking 1980s, and my mom still thought MAD would rot my head if I read it. That's a magazine, man, that's something.

Labels: this week in comics