What follows is time travel.

The past few days have seen some considered posting on the decline of the Direct Market. So, in the spirit of commemoration, here's an essay I wrote in late 2005 about one of the native Direct Market species: the superhero Event crossover. It was originally composed for a print venue, so as to introduce and explain the contours and implications of the thing to an audience not necessarily common law wedded to DC/Marvel storytelling-marketing schemes. The idea is that you can choose not to read these stories, but you nonetheless have to cope with them, so you'd better know what you're getting into, what kind of tent to bring, how to repel bears, etc.

It ultimately wasn't accepted for publication, no doubt owing in part to my cheery insistence on talking about comics I readily admitted to not having read, to say nothing of my tone and structure, which in retrospect seems intermittently evocative of a James Quall-like celebrity impersonation of David Foster Wallace. I had footnotes, oh yes, which I've now either worked into the text proper, converted to hyperlinks or just plain deleted if nothing of even subatomic value was lost. Obviously the images are new, and the format is switched up a little, but it remains something I wrote three and a half years ago.

Still, even though all of the information and commentary is entirely specific to that period in time, I think it retains a certain snapshot quality today, hence my retaining even the bits that all but beg for editing, like the Terra Obscura stuff. These basic mechanisms still endure, and even individual aspects sometimes recur - I'd totally forgotten that the issue of Batman's identity had been hyped up as an aspect of the Infinite Crisis fallout too. Something to keep in mind as the eulogies are given, and the retailers stand around like Tom Sawyer. That's life in the funnies.***

Ruminations On the Topic of the Contemporary Superhero Event Comic, Having Barely Read Infinite Crisis and/or the Rest of It. I. Comics Series Begun In 2005 That I Have Not ReadA.

Day of Vengeance.

B.

The OMAC Project.

C.

Rann-Thanagar War.

D.

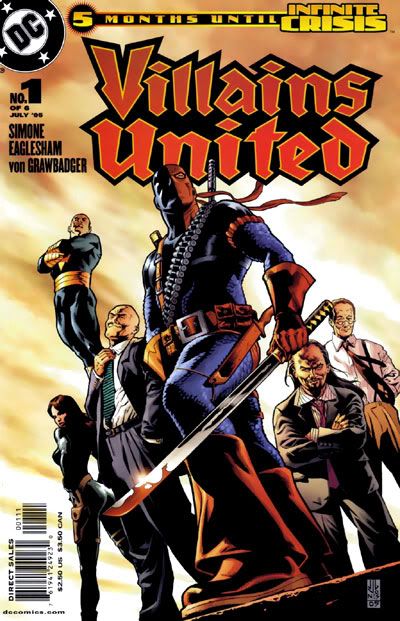

Villains United.

E.

House of M.

F.

Infinite Crisis. (Well, not as closely as I

could read, at least.)

Now, why would a fellow be moved to write a bunch of things about books he hasn’t even read?

Let me tell you, then, about a book I

have read.

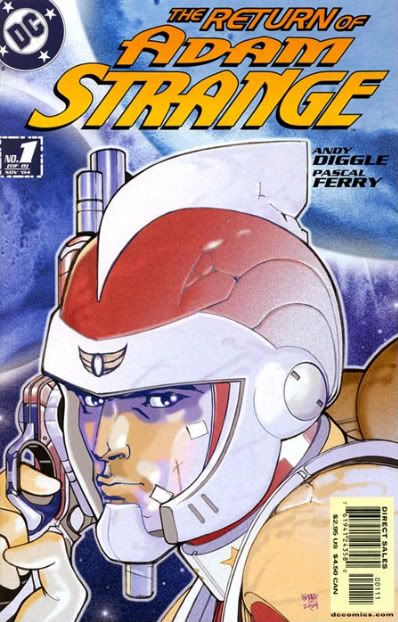

II. The Unfortunate Defeat of Adam Strange Adam Strange

Adam Strange was an eight issue miniseries, published by DC Comics in 2004 and 2005. As one might expect from the title, it was a revival of the classic protagonist of

Mystery in Space, who’d made the occasional guest appearance here and there in recent years. There was a two-part 1998 storyline in

JLA, issues #20 and #21, written by Mark Waid with pencils by Arnie Jorgensen and inks by David Meikis, and the 2004 Julius Schwartz tribute book

DC Comics Presents Mystery in Space, with one story by Grant Morrison and Jerry Ordway/Mark McKenna, and another by Elliot S! Maggin and J.H. Williams III.

The latter book was additionally noteworthy as by far the strongest of an octet of similarly-branded Schwartz tributes, with the Maggin/Williams story providing sleek, effective entertainment, and Morrison/Ordway story standing out as one of the few to vigorously engage with the subject of the banner's toasting and applauding, mixing sci-fi adventure with political comment in the art and dialogue, with a caption-fueled line of musings on the contrast between Schwartz’s editorial approach as a comics futurist and the social realities of his era laid atop - thus, the story’s very form is ‘torn between two worlds,’ as is the historical positioning of the work under examination, and Adam himself in the story proper.

And with Adam Strange the series, writer Andy Diggle, for the first few issues at least, did maintain a crisp action storytelling beat, the title character careening all over the place on a quest to find out what happened to his beloved Rann, as artist Pasqual Ferry provided plenty of energetic pulp poses and postures, assisted mightily by the candied colors and spackled sheen of colorist Dave McCaig. I got to the book a little late, I confess, but good word-of-mouth turned my attention, and I was fairly compelled. Again,

at first.

In retrospect, problems were evident with the book from about the halfway point. There was far too much attention paid to reintroducing seemingly every outer-space character crowding up the DC back catalog, and the pursuant characterizations were not compelling enough to make it seem like more than an exercise in nominal refurbishment. But - at least the book sped forward, and at least a sweet, junky sense could be made of it all.

Diggle, in an interview with

Comic Foundry [NOW OFFLINE -Ed], would later make a reference to how the book taught him “...t

o always agree to the ending before you start. Having the goalposts move mid-game is never a good idea.”

The finale to Adam Strange read to me as significantly compromised, rushed in a certain unnatural direction. The resolution of a fight with the series’ main heavy is, oddly, shunted off to the side. Previously unseen characters appear suddenly to offer painfully abrupt aid at crucial moments. Logic contorts in order to send the planet of Rann zipping straight into the proximity of Thanagar, home of many a winged entity, with no immediate means of escape. There is no finale, no resolution, not even the moment’s rest afforded the gallant heroes and bold crews of the silver screen serials the series occasionally evoked with its bombastic cliffhanger endings.

No, there would be war between Rann and Thanagar. And it would have its own miniseries. And there would be a totally different creative team. And it would be one of several simultaneous miniseries. And they would feed into

another miniseries. And there would be tie-ins and relations and impact, all over the map, tendrils of gelatinous continuity snaking outward to embrace wide swathes of the shared DC Universe.

It would be, in short, an Event.

And if such things are going to impose themselves on my reading experience, regardless of whether I'm reading them or not, then I find I can’t help but study them, or at least how they appear, what they’re made of, what they seem to be and how they seem to work.

III. Numbers Don’t Lie - They Watch Their Words

Infinite Crisis is the current DC Universe Event.

Infinite Crisis is a seven-issue miniseries.

Infinite Crisis is a sequel of sorts to the nostalgia-charged yesteryear line reorganization

Crisis on Infinite Earths.

Infinite Crisis inspires a number of tie-in issues of continuing titles.

Infinite Crisis follows directly from a quartet of lead-in miniseries, along with their own tie-in issues of other continuing titles.

Infinite Crisis feeds off of a character tone accrued from months of disparate storylines and motivations for its thematic weight.

Infinite Crisis is the instrument by which the directions of several continuing titles will be altered; in fact, it will be setting off yet another line-wide relaunch among DC superhero books.

Infinite Crisis is also a big seller. According to sales charts

posted at ICv2.com, tracking sales from Diamond US to comic specialty stores, Infinite Crisis #1 sold an estimated 249,265 copies in October of 2005, the month of its initial release. In second place, dropping down to an estimated 134,429 copies, was issue #7 of House of M, an eight-issue miniseries from Marvel. House of M is Marvel’s latest Event.

There’s a lot of considerations to take into account when reading these numbers - for one thing, they only represent sales from Diamond to comics stores, not from comics stores to readers. Also, the numbers on Infinite Crisis have doubtlessly been goosed by the presence of a variant cover, which, without fail, guarantees that some stores will be beefing up their orders to supply their customers with additional collectable material. Plus, one ought to take into account the price tags of each individual issue ($3.99 for Infinite Crisis, $2.99 for House of M) to grasp the true sales impact of each title.

After all of this, one gets the sense that they’re reading entrails more than anything, but fortunately the message is the same - titles like Infinite Crisis and House of M are worth big money, and sell big numbers.

They’re not alone, mind you - also in the top five that month are issue #12 of the high-profile Brian Michael Bendis relaunch

New Avengers, the second issue of the Alex Ross-powered alternate universe project

Justice, and issue #1 of

Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man, both a new Spider-Man title and the kick-off of a big Spider-Man family crossover. Of course, with the above slew of caveats in mind, you ought to note that by that fifth place slot the sales numbers are down to 85,761. By fiftieth place, the numbers plunge to 36,450. There’s a grand total of one book not released by a Marvel or DC-owned label in that top fifty -

Spawn #150, at number 45, from Image.

But Infinite Crisis’ numbers in particular are inordinately large, second only to those of issue #1 of the Frank Miller/Jim Lee book

All Star Batman and Robin, the Boy Wonder from July 2005 (261,046 in its initial month of release), which logged

the highest numbers of its sort since ICv2 began tracking sales in 2001. (Yes, there was a variant cover on that one too.)

And the big trick is that Events like Infinite Crisis and House of M (which debuted at 233,000 in June of 2005, no potatoes and onions itself) don’t just score big sales for

themselves - they lift up affiliated books, boosting sales of ongoing titles that tie in, and even supporting supplementary miniseries, lead-ins and epilogues. Thus, their influence extends beyond the reach of their covers, a trick that can’t be as easily managed by plain old New Avengers.

Part of the appeal of Events to their target audiences, after all, is precisely that they are not confined to a mere miniseries and an inevitable collected edition. If you are a reader of Batman, for instance, the story will affect Batman, and you ought to read it. If you are a fan of Wonder Woman, or Superman, or Hawkman, or Birds of Prey, or the Demon - same thing. The universe itself will be shaken by these occurrences, as that is part of their appeal, the necessity that brings in their increased sales both within and without the contours of the primary Event series itself.

As I’m sure you’re muttering to yourself right now, yes, this does seem to cater solely to an extremely devout audience. Yes, this does appear to erect a difficult-to-surmount barrier for new readers, especially when calamitous Event fallout suffuses a large number of books, occasionally upsetting seemingly unrelated storylines (see: Adam Strange). This can act as an annoyance to constant readers who are otherwise uninterested in the overarching megastory. But I posit that it’s virtually impossible to be reading superhero comic books from Marvel or DC today without feeling the grip of the Event surrounding you. One is occurring, or one is on the way.

This inspires certain thoughts in the reader - even if one is not predisposed toward interest in such stories, perhaps they’ll want to look at how these things work, and ponder their mechanics, their most naked appeal. And all Events don’t proceed in the same manner.

IV. The Anatomy SyllabusInfinite Crisis is, if nothing else, encompassing. For one thing, it feeds off of a tone that’s been established for months and months throughout DC superhero books, one that can most simply be traced back to

Identity Crisis, a prior, less swelled Event that began in August of 2004.

It was a somewhat simpler thing, a seven-issue miniseries centered around the mysterious murder of the Elongated Man’s wife - it had some tie-ins in ongoing titles, it purported to reveal the secret truth behind pieces of DC back-continuity, the hidden poisons of the Silver Age, and it set up future clash between the iconic DC superhero characters, stemming from lies and arguable immorality among the lead characters.

The seeds of discord thus sewn, May of 2005 brought

Countdown to Infinite Crisis, a one dollar, 80-page book, created by a slew of writers and artists, essentially devoted to setting up the quartet of miniseries that would feed into Infinite Crisis, climaxing with the attention-grabbing execution-style shooting death of the Blue Beetle, just to drive home the sheer import of the occurrences therein.

Those miniseries -- the OMAC Project, Villains United, Day of Vengeance, and Rann-Thanagar War -- each stretched in premise to cover different aspects of the DC Universe, from heroes and villains on the ground to technology and magic to the far reaches of outer space. These series essentially led into Infinite Crisis, although their own action sometimes spilled out into tie-ins of varying import, of which there were over twenty total; the most immediately noticeable example of this is when a major plot point in the OMAC Project wound up actually appearing in a tie-in issue of

Wonder Woman, scripted by OMAC writer Greg Rucka, rather than the series proper.

Rucka later apologized for the situation in

an interview with Newsarama: “

I want to say, before anything else that we tried very hard to build OMAC so that you weren’t obligated to buy anything else, and we failed.”

As suggested above, I’ve not read any of these ‘feeder’ miniseries. I can’t speak for their quality as stories. What I

can speak for is their volume, their grasp - if nothing else, there is the appearance of touching nearly

everything, and that is perhaps the key: before it even began, Infinite Crisis had its fingerprints all over the DC Universe, whether through mere reference or storyline disruption or the conveyance of the major plot points of one book in another book.

Messy, but it gave the appearance of permanence, of a swaggering force rumbling across the landscape - it’s thus easier to see the actual Infinite Crisis series as something of sweep and might, capable of upsetting universes, which is just the suggestion left by the storyline itself, or at least the two issues published as of this writing. After all - it’s already wiped out stories, and it’ll wipe out more before it’s through. Put into a few words, it has the air of permanence.

In contrast, House of M was from the beginning set up with a sense of restraint about it. Spilling out of writer Brian Michael Bendis’ attention-grabbing run on

The Avengers -- which eventually led to the relaunch of the book as the aforementioned New Avengers; see how these things tie together? -- the story involved something of an alternate universe being created, with assorted Marvel characters taking on new roles, with the obligatory shattering changes awaiting upon the restoration of the original world. In accordance, various ongoing books temporarily changed to reflect the new realities of the House of M universe.

House of M is an Event, much like Infinite Crisis - it shares many of the same traits: it has a single miniseries core (eight issues here), it reaches beyond the bounds of that core into tie-ins, and it purports to shake up the applicable superhero universe at large, promising much for the future. But the very whiff of ‘alternate universe’ surrounding House of M perhaps leaves it grasping for what Infinite Crisis holds firmly in its fist - having set up a plainly removable alternate world for the action of the story, House of M perhaps makes itself too transparent in concept. It is evident that some things will be kept, and some will be left behind upon the inevitable dissolving of the alternate world. All tie-ins are carefully secured within the confines of this fantasy; anything can happen, but anything can be thrown to the side at the Event’s conclusion.

(Let’s keep things in perspective, though - none of this prevented the Chris Claremont-scripted House of M epilogue one-shot

Decimation: House of M - The Day After from selling 96,734 copies

in November.)

This is frankly true of most world-shaking superhero storylines; even minor bits of history and character are up for erasing by a subsequent editorial mandate or creative team. But from my perspective, House of M seems almost self-referential in this way, as far as concept goes. The ‘alternate universe’ story is hardly new, but when paired with the invasive, arguably sloppier Infinite Crisis, it seems coy, withdrawn in its promises for the future, and those are important things for any Event - once you’ve purported to shake up a continuing world, readers will obviously want to read about that world post-shaking. Taken on such terms, House of M seems curiously (if honestly) uncertain about itself. DC might well triumph through force of excitement, and the feeling that things are really happening in their line, that there’s no going back for anyone.

The superhero-acclimated observer can sense the appeal, and perhaps begin to understand how the march has continued to such financial success for this year and one half.

V. Seeing ThingsI can sense it, at least. I find myself inadvertently overlaying the blueprint of the Event over largely unrelated books.

For example, I recently re-read the first volume of

Terra Obscura, a six-issue miniseries begun in August of 2003, released by the DC-owned America’s Best Comics, plot by Alan Moore and Peter Hogan, script by Hogan, and art by Yanick Paquette and Karl Story. It’s a spin-off featuring characters ‘introduced’ in issues #11 and #12 of the Moore-written

Tom Strong, though they’re actually public domain superheroes originally presented in books by Golden Age publisher Nedor Comics.

The plot of the initial Terra Obscura storyline involves seemingly every superhero in its particular universe joining up to battle a terrifying common threat that threatens to undo their world by unraveling time itself. And moving through, parsing the book’s large cast, I began to feel that the story was in fact simulating a world-changing Event, except it was necessarily only providing the core miniseries.

Relationships between characters are alluded to throughout the story, there’s abrupt guest appearances and references to earlier adventures, all of which remain unknown to the reader, since no other material beyond the original Tom Strong appearances exists - it feels very much as if its intentionally leaving things out for fantasy supplementary texts, forcing the reader to fill in the tie-ins with their own imaginations. It almost mocks the set-up of a world-changing story, but remains quite successful in retaining coherency whilst offering a gentle sense of missing things, evoking a type of loss in the reader, a desire to search out more than cannot be fulfilled. I realized this upon my initial reading, but now it seems especially canny in its construction, almost prescient in its toying with Event concerns.

(There is also currently a second Terra Obscura available; it was also a six-issue miniseries, dealing mainly with the type of World’s Finest relationship riffs that one presumes Moore can do in his sleep at this point. Still, a sequence in which a sociopathic puritan Batman figure keeps himself alive by literally implanting his brain in the head of his kid sidekick offers some pleasant revamp-minded kick of critique. Both series are now collected into trades.)

More contemporary is the quite excellent Grant Morrison-written

Seven Soldiers project, which kicked off in April of 2005; a thirty-book mass of releases, this project can be seen in the context of current Events as an experiment in nearly all tie-ins, with very little in the way of a core story. Seven Soldiers consists of a pair of bookending one-shots, with seven four-issue miniseries inserted in between. Part of the premise of the project is that the title heroes of the seven miniseries never actually meet one another, though their actions go a ways toward defeating yet another world-menacing threat.

It’s a bit of a ship-in-a-bottle spin on the Event, with the spotlight thrown on characters caught up in events that they rarely comprehend in full - some of the miniseries are (as of now) barely connected to the ‘main’ plat, whole some are tightly connected. The rub is, there’s hardly any

core to speak of here, allowing for Morrison to riff on endless variations of the theme of transformation, while commenting upon such metafictional concerns as the nature of the superhero revamp, and the role of the hero in an increasingly dark universe.

In this way, the project often seems like something of a response to the often gloomy subject matter of DC’s main continuum of Events - actually, it is strongly suggested from the content of Infinite Crisis’ two extant issues that the Event itself means to engage with the nature of 'dark' superheroics through the appearance of an earlier continuity's Superman-family cast. Such decadence is not within the scope of this particular piece, but it’s an interesting thing to consider as both projects move forward.

The trick with Seven Soldiers is that it probably succeeds better in this way than in the manner suggested through its writer’s own promises about its modular setup - Morrison had noted in September, in an interview with Comicon.com [NOW OFFLINE -Ed] that "

If you choose to buy only Klarion: the Witch Boy, say or The Manhattan Guardian you'll still get a complete and satisfying four-issue mini-series which sets up the characters and establishes them for future adventure." That prior March, a more ambitious Morrison told Daniel Robert Epstein of Suicide Girls: “

Each of the four issues are also self-contained reads because I wanted to try a completely modular story.” This theory was pretty much dead in the water in my mind as early as the first (cliffhanger) ending of the first issue of the first miniseries.

Yet the element of 'spillover' present in actual Events (and duly simulated in Terra Obscura) also isn’t quite present, as is perhaps necessary given the resolutely self-contained nature of the affair. The most enjoyment of the project can probably be extracted by viewing it as a thirty-issue maxiseries, cross-cutting from happening to happening and providing a mosaic of forgotten characters being made better in a worsening universe. But we can always see the edges, the contours of the universe in this book. Part of the appeal of the Event, I think, is that it stretches onward and farther.

Does that make for worse storytelling on the whole? Likely. But perhaps direct 'telling of a story' is no longer the only concern of such comics.

VI. InfinityBack in the world of the huge-sellers, the earth-shakers, we continue to rumble forward. Both Marvel and DC have announced their 2006 plans.

Following Infinite Crisis, the countless relaunched, revamped DC superhero books will be leaping forward one year into the future with new creative teams (I’m especially looking forward to Walter Simonson and Howard Chaykin’s Hawkman revamp,

Hawkgirl), with a weekly omnibus series titled

52 set to fill in the continuity gaps.

Marvel has launched a number of post-House of M miniseries under the banner of

Decimation; later this year, a cosmic-centered storyline titled

Annihilation, consisting of its own prologue one-shot, quartet of feeder miniseries, and climactic self-titled miniseries. And, most pertinently, it’s prepping a more line-wide Event titled

Civil War, to begin in a Bendis-scripted one-shot titled

New Avengers: The Illuminati and later spin out into a multitude of yet unannounced miniseries and tie-ins, many featuring the involvement of writer Mark Millar. It will

also tie into House of M. The world of Marvel superheroes will change. Etc.

And if it strikes you as odd that so many major things seem to be happening on such a regular basis, well, first of all you have lots of sales figures to read, and plenty of short-term benefits and long-term detriments to infer, or maybe it’s the other way around if you so choose to see it that way. What is clear is that the mechanics of the Event will remain relatively constant, throughout all of the change - the story will spread, it will span a continuum, it will promise permanence and other things for the future.

The future.

Thinking back on the recent reactions to the conclusion of House of M, one recurring sentiment really struck me. It was the attitude that the story itself wasn’t all that good - too spread out, a little bloated, the tie-ins were kind of weak. But: the plot points it hit, the new set-up it created from the ashes of the old - it held a lot of

promise for

future stories, the potential for interesting things to come.

And aren’t all of these things looking toward the future? Isn’t forward momentum a vital component of all of this galaxy-quaking? Maybe the mechanics of the affair transform the stories of these Events themselves to something of secondary importance, something beneath what is promised. After all, these superhero universes - they’re never going to end, right?

In dealing with such potentials, maybe I’m in a safe place, having read so little. Maybe I just need to

look forward to things as well, things that look good, and keep my money in my pocket. Just keep

thinking.

What happened in that lost DC year?

How will those few remaining mutants get by?

Who will be Batman? Who will be Catwoman?

How will Walt Simonson and Howard Chaykin handle Hawkgirl?

Ah! To be one of the engines of the current market, and so very nearly beside the point!