Désastre Hurlant (T9): The Good, the Bad and the Temporarily Resurrected

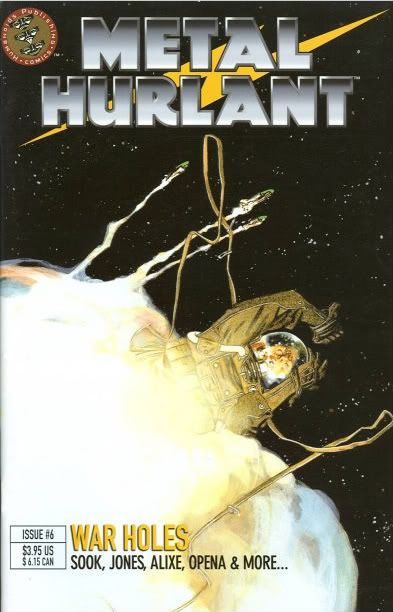

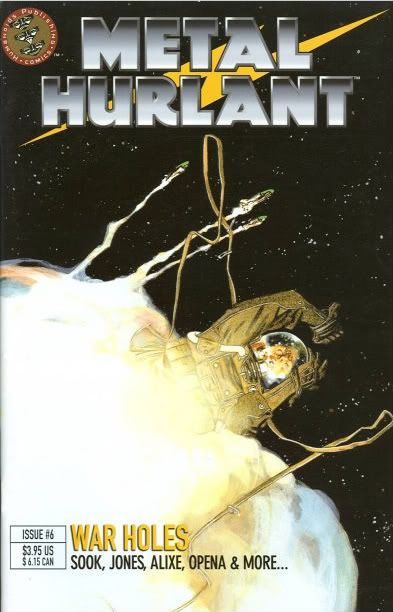

In 2002, Humanoids began the most ambitious project among their various pamphlet-format adventures: a revival of no less than Métal Hurlant itself, the great house magazine of Les Humanoïdes Associés, dormant since 1987. It was to be a special, distinctly international incarnation, a publishing union of Humanoids and Humanoïdes, with artists from all over the globe joined together "like a lightening bolt between two continents, from Paris to Los Angeles," as the first issue's editorial enthused.

And they kept it pretty much synced, for a while. The English-language edition ran for 14 issues, until 2004, while the French iteration saw 12 issues, in much the same format -- pamphlet-sized, initially thicker -- with similar (but not identical) content. The two series were released on a like minded schedule, and collapsed at roughly the same time; a 96-page special issue of the French edition emerged in 2006, apparently as a means of burning off some of the later stuff that appeared in only the English version, although there was some original content too.

It's fascinating to read through the stuff again today; Humanoids obviously saw the series as its bold flagship, and a forum for all sorts of promotion and personality. Editorials by publisher Fabrice Giger and managing editor Paul Benjamin are charmingly uninhibited and just a little pretentious, prone to colorful metaphors (Giger on transcontinental publishing: "the sword is heavy and hard to handle"), dramatic political exhortations (dated November 3, 2004: "in my dreams, the good guys always end up vanquishing the bad guys; I wish that in four years it would be a reality") and old-timey Team Comics fist-pumping for the good works done by Our Fellow Travelers at Fantagraphics, Image, Top Shelf, etc. - even Marvel, but don't be a superhero zombie, fanboy/girl!

There was a publicity motive at work too, naturally - the differences between the English and French editions seem to have been guided by what Humanoids wanted to promote in North America, in terms of authors, genres and formats. A Travis Charest Metabarons story would not run in the English Hurlant if it could be better sold as part of a Prestige Format one-shot like The Metabarons: Alpha/Omega. Sometimes projects would be announced, only to fade from view - did you know Humanoids planned to release Milo Manara's Giuseppe Bergman in North America (presumably 2004's The Odyssey of Giuseppe Bergman, since that's all Humanoïdes had published of the series at that time)?

I have to wonder if the imminent DC deal didn't scuttle that plan; the DC/Humanoids books may have undone the editing-for-content that went on in Humanoids' pamphlets, but I suspect DC may have been reluctant to take on such overtly sexual material.

Interestingly, Métal Hurlant never displayed the DC logo or listed DC personnel in on its masthead, even after the DC/Humanoids partnership began and the series started appearing with DC's solicitations. Perhaps something had to be left to Humanoïdes; an effort was made to preserve the new Hurlant's continuity with its ancestor, from the French edition maintaining the original issue numbering (it started with #134) to the English edition trumpeting issue #10's return of Richard Corben, surely the first great example of Hurlant's international eye. That was also the issue to announce the DC/Humanoids partnership, prompting publisher Giger to pronounce the series, four subsequent issues from evaporation, as "comics without borders."

Yet some boundaries couldn't be denied. My favorite thing in the revived Hurlant was a regular column by Humanoïdes co-founder Jean-Pierre Dionnet, who served as EiC of the old Hurlant for most of its existence and wrote a similar column in apparently every issue. Of the 'creatives' involved in the birth of Humanoïdes, Dionnet is easily the most obscure; he was a writer, but not an artist, and the only translated work of his that springs readily to mind is a 1977 Heavy Metal feature and subsequent book collection, Conquering Armies, a suite of sometimes-fantastical stories about mighty forces becoming somehow undermined, drawn in a shadowed heavy realist style by the late Jean-Claude Gal.

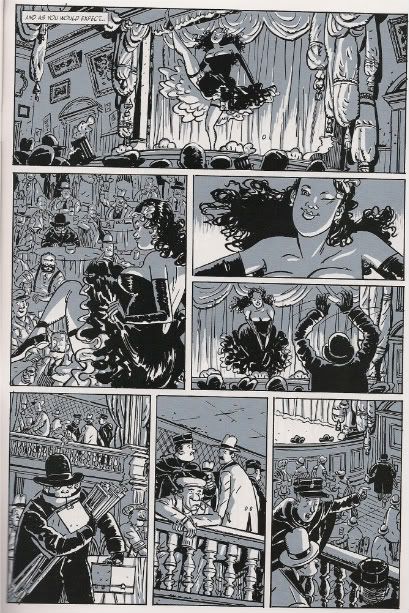

The guy wrote a good column, though, very much a blog-style point-by-point "what I'm reading-watching just now" kinda thing, ping-ponging from Kazuo Umezu to Lili St. Cyr to the dvd releases of Lobster Films to Avatar comics to Frédéric Coche to seemingly half of the U.S. mid-century pin-up/advertising art collections published between 2002 and 2004. Few language barriers were acknowledged, and Bud Plant was oft-toasted. At one point he mentions preparing for a project with Warren Ellis (the first and last I've heard of that) by reading through the man's complete works - an obsessive after my own heart!

But Dionnet also brought his acknowledged biases to the table, and refused to mince words. In his first column, he reflected on having difficulty coping with the story-first comics aesthetic of acclaimed works written by Alan Moore and the like, in that his own approach to comics had typically favored the promotion of splendid visuals as facilitated by script. If you're going to interface with North American comics, I think you have to acknowledge the minority status of that perspective, and only after a while can Dionnet (himself a writer, remember) understand the possible facility of visuals as supplicant to writing, even if the visuals themselves seem distinctly unexciting. And Dionnet didn't waste time puzzling over the C-list either; we're talking Steve Dillon on Preacher ("hideous") and J.H. Williams III on Promethea ("hippy art nouveau overflows"), the latter comment landing in the very same issue where Williams illustrates a Alejandro Jodorowsky short. J'accuse!

I think that kind of perspective is valuable, though, and probably not unexpected from the guy who edited Moebius & Druillet in their prime. You need only look at an early issue of Heavy Metal to see these values in full force, not that Dionnet was thrilled with what the American magazine became: "a drooling esthetic, falsely poetic and truly cheesy in a way that reminded me of black velvet paintings, with flying horses and sterile images of bimbos with perfect hairdos." It really was mostly a positive and enthusiastic column, though!

Dionnet was very enthusiastic about Jodorowsky too, and no doubt simpatico with his artist-first method of comics creation. And indeed, it's often easy to watch Jodorowsky's work rise and fall on the strength of his visual collaborators.

***

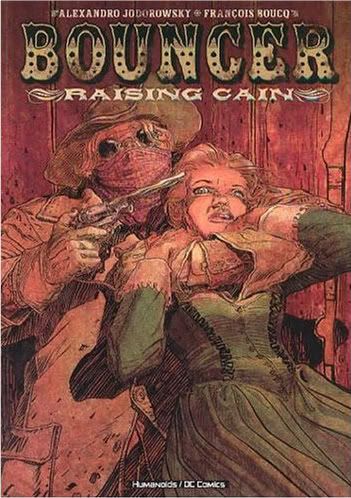

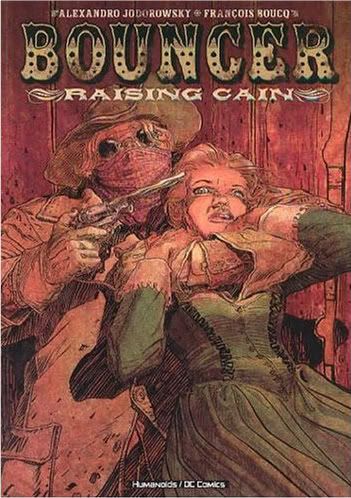

Bouncer: Raising Cain

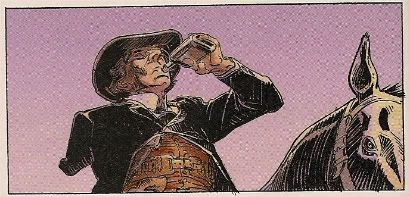

For example, this book sees Jodorowsky teamed with a genuinely excellent artist, François Boucq. Like Moebius, Boucq is a notable writer/artist, although nothing of his solo work has been released in North America beyond Catalan Communications' 1989 edition of Pioneers of the Human Adventure, a fine, small collection of archly surreal social commentaries from the pages of (À Suivre). Catalan also released two of Boucq's funny, eccentric collaborations with writer Jerome Chayrin: The Magician's Wife, winner of the Best Comic Book prize at Angoulême in 1986, and Billy Budd, KGB. Boucq also won the Grand Prix de la ville d'Angoulême in 1998 for his cumulative body of work, so he has no lack of respect on the French scene.

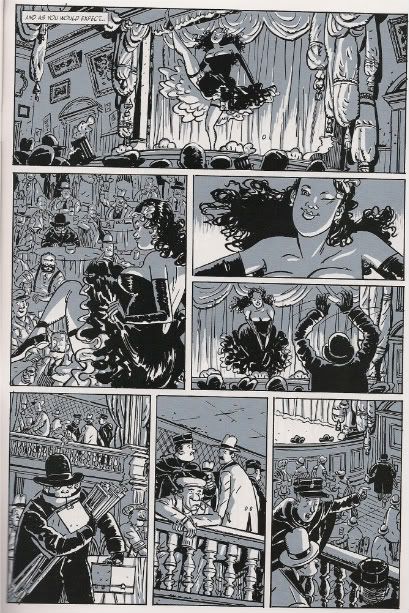

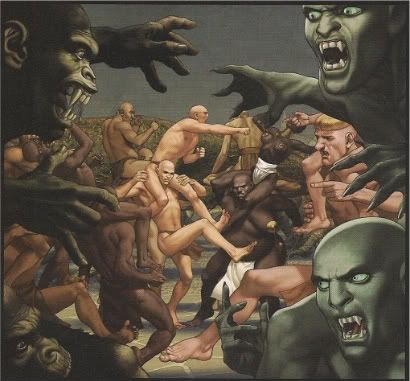

For our purposes here, I'll also concede that Boucq strikes me as the ideal collaborator for Jodorowsky, even more so than Moebius. He has a wonderfully fleshy, molded approach to character art, with a keen eye for costuming and a great sense of comedy, typically pitting his soft-looking humans against disconcertingly realistic animals and detailed, evocative environments. Who better to convey the longing for sensitivity and oddball sexuality redolent in Jodorowsky's characters? Two people kissing seems like an oddly hilarious clash between the primal forces of the Earth to Boucq, which is naturally conductive to the archetype-driven action of Jodorowsky's plots - and he can do fantasy too!

Bouncer is the most recent collaboration between the two, a Western-as-in-gunfighters project begun in 2001 and currently up to vol. 6 in France; this sole DC/Humanoids book collects the first two French volumes, which appear to complete the series' initial storyline.

It's a good work, likely just the thing Kim Thompson had in mind when he cited the French comics industry for its 'crap': "that bulwark of solid, unpretentious, accessible genre fiction - a more or less undistinguished mass of okay-to-good comics that might catch your eye and give you a thrill, that loyal fans would buy out of habit, and anyone else might just pick up for the hell of it." If the Western were at all a viable genre in North American comics -- and, by and large, it's not -- this wouldn't be a bad piece to employ as a model for how to get it done.

Granted, it's still chock-full of Jodorowsky's writerly concerns, particularly his constant focus on the family. A solid 1/3 or so of the book is taken up by flashbacks explaining how the titular employee of the joyous-looking Inferno Saloon became a haunted man of violence - his mother was a child of rape and an adolescent prostitute who forged herself a place in a brutally masculine society, with the eventual, brutal aid of her three sons. But her greed and ambition eventually led them to knock over a steam engine ferrying the legendary and very subtly named Eye of Cain diamond, which eventually causes them all to go bonkers while in hiding; it's definitely more Treasure of the Sierra Madre than El Topo.

Brother inevitably turns against brother - one loses an arm, one loses and eye and the third loses his steel. Mother is so horrified with this breach of the family unit that she hangs herself, but only after hiding the diamond, prompting the one-eyed brother to slice her belly open and dig through her entrails for the treasure, which I know from experience tends to cause rifts between siblings. The not-physically-maimed brother leaves to find god and father a child with an Indian woman, but the end of the Civil War brings the return of his one-eyed counterpart, now leading a faction of bandits who refuse to acknowledge the Confederacy's surrender and hungrier than ever to find that lost diamond, which could power his force for years. Hidden under the floorboards, the child is baptized in the spilled blood of his murdered parents, and sets off to find his one-armed uncle, the Bouncer.

And while none of this gives Boucq quite the best chance to show off the fleshy-surreal side of his style -- even a Peyote-powered hallucination sequence comes off as distinctly grounded -- his sun-baked colors do effectively mute the romance of blood and dust into a parched, dirty struggle between fundamentally pliable humans. Everybody is sort of wrinkled and gross, even the 'beautiful' women, which does scratch at the shared humanity suggested by Jodorowsky's backdrop of racism and political-minded brutality.

It also kind of offsets the writer's taste for cross-genre cheese, which does coexist with the period verisimilitude. For all its attempts at suggesting departures from stereotypical femininity, this is a Jodorowsky story, and thus a work of archetypes questing. There's several Garth Ennis-like reflections on fabulous killing as a defining masculine trait, capped off with an eye-rolling moment in which the Bouncer's nephew completes his training-for-revenge and takes a bath, only for a nearby woman to comment on how large his prick is. It's the kind of book where an enlightened new schoolmarm from out of town raises a ruckus with her liberal ideas about Native treatment, but still sets several pages aside for the comedy stylings of a drunken Injun sputtering pidgin English.

Let's hope you're also ready for some high melodrama, the sort that assures Our Young Hero's burgeoning romance with a young lady cannot pass without remark from the familial theme. That part seems a little more fitting, though, small as it makes the Old West seem; even the worst, most murderous villain is ultimately reduced to a child in the end, in spite of all macho activity, shouting at Mommy while longing after her forgiveness. You'll find some escape from that motif in Jodorowsky's work, but not much; even his 'small' works like this are stained with trauma, although littler stories offer less a full-scale enlightenment for their characters than a modest possibility of grace. At least the world itself seems especially responsive here.

***

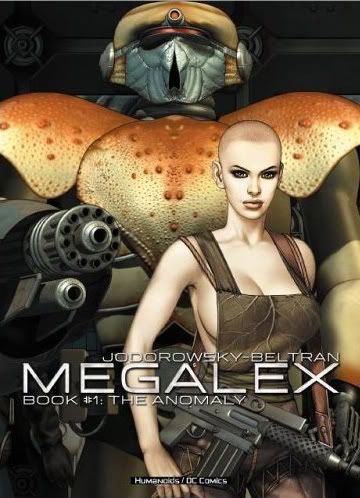

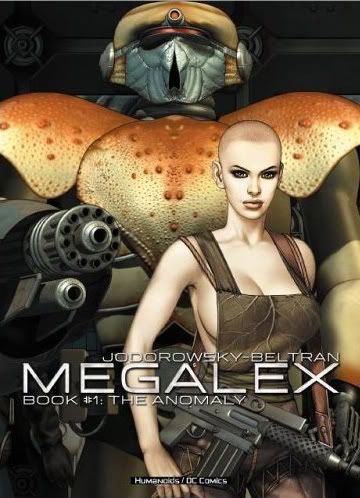

Megalex Vol 1: The Anomaly

And on the flip side of responsiveness and (relative) modesty, we have Megalex, which Humanoids positioned as the first 'major' serial of the revived Metal Hurlant; the second was Fragile, which did not finish before Hurlant sank, although the DC/Humanoids collected edition restores all missing chapters.

'Serial' is a tricky term, of course. As far as I know, the three-volume Megalex (1999-2008) behaved as your typical direct-to-album release in Europe; it wasn't even part of the French edition of Hurlant, leading me to guess that Humanoids made an educated guess that what Direct Market readers would really like to see in a new anthology was more Jodorowsky, and, Jean-Pierre Dionnet's black velvet assertions notwithstanding, a big ol' bunch of hot hot CGI ladies with improbably enormous breasts. And since the third volume wasn't even close to finished at the time, the adventure simply stopped at the end of the French vol. 2, which is as far as the DC/Humanoids collection goes as well.

I wonder if this series had anything to do with La Guerre de Megamex (The War of Megamex), a project Jodorowsky had intended to begin with Akira creator Katsuhiro Ōtomo in the early '90s - surely Megalex's city vistas and sprawling melee action seem keyed to Ōtomo's particular East-West blend of comics maximalism. Tragically, we don't have Ōtomo on hand for this one. We have Fred Beltran.

Beltran, you'll remember, is the guy who devised the updated color scheme for the 'new' versions of The Incal and its prequels. He also worked directly with Zoran Janjetov to create the super-shiny digital look of The Technopriests. This is apparently his first work with Jodorowsky as sole artist, and he rightly seizes the opportunity to attempt the annihilation of the human trace altogether by posing 3D models inside a a wholly CGI environment - Batman: Digital Justice, eat your heart out!

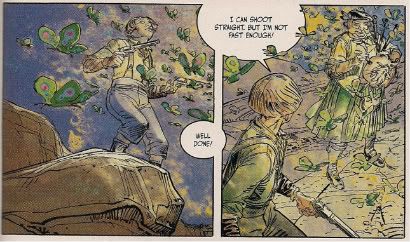

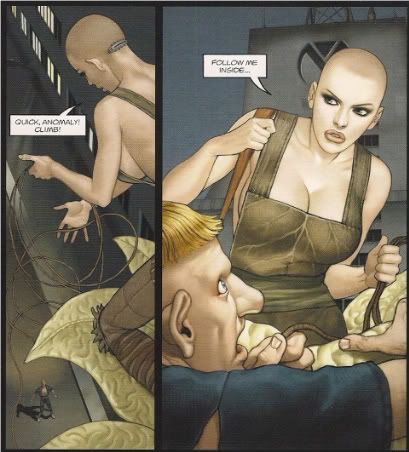

And while I'll readily admit that Beltran's 3D modeling is better than average -- and do note that vol. 3 seem to pursue a different style entirely -- it still doesn't hold much appeal at all to me. Jodorowsky's plot is among his most off-the-cuff in feel, positing a future civilization where drug addiction is mandatory and labor is forbidden, and every atrocity imaginable is processed into entertainment for the lazy populace - it's basically those five or six bits in the Incal with everyone watching the action on tv, stretched well beyond the breaking point into an entire series.

Banalities and contrivances pile - a strange attack on the city leaves an assembly line police clone overgrown and awkward (nonconformity!), mandating his escape from society into the oddball confederation of (literally) underground mutant rebels who desire to topple the city with the sleeping might of nature: giant roots and talking lizards and the like. But Beltran's art is entirely unsuccessful at portraying anything 'natural' without it looking dug out from a plastic cast; while I suspect the 'off the assembly line' nature of the city's robots and cloned citizens were supposed to play to Beltran's strengths, it's nonetheless puzzling how an earth vs. tech plot like this even wound up with an all-CG artist whose talents are almost entirely predisposed toward the antagonistic 'tech' side of things.

Or maybe that's foreshadowing? I don't know, but Beltran's eventual, not-in-this-book switch in visual approach suggests otherwise.

At least Beltran does manage the perverse flourish of basing every last female character, from the obligatory cruel mother figure to all the various love interests, off of the same woman, his own wife - Jodorowsky must have appreciated that!

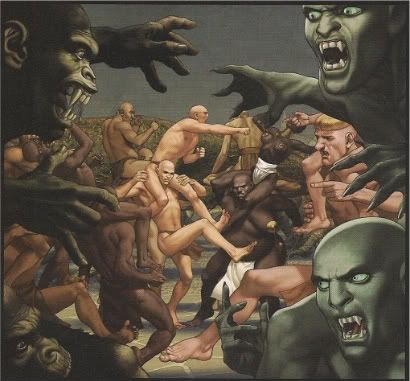

Likewise, some of the writer's odder ideas -- a sad, wicked princess whose longing for intimacy is always ruined by her aptitude for immolating anyone who touches her skin, a labyrinth master named Cabot-Chadday (who may be a pair of twins, or possibly just one guy and an imaginary friend) who fathered the mutants with a talking wolf he insists is a beautiful woman, a tribal contest of champions that plays out in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome piggyback battle royale fashion -- congeal into some effective distraction, but there's no salvaging the whole (er, 2/3 of a whole) from its patent disconnect of presentation and content.

Even the pacing seems spoiled by the art, with nearly all of the French vol. 1 (i.e. the first half of the U.S. book) functioning as a chase scene through Beltran's computer backgrounds, and vol. 2 (for which I expect the technology was supposed to improve) split into piles of tiny panels populated by half-expressive characters for the purpose of dumping out the necessary plot. It's a mess, but a telling one - just try and think of exactly the same content drawn by a Katsuhiro Ōtomo, and you can all but see the improvement.

It's too bad - the revived Hurlant did sport some decent-looking pieces during its short life, and the quality was generally a lot higher than that of the still-enduring Heavy Metal. Jodorowsky's short stories with the likes of J.H. Williams III and José Ladrönn were often cutesy but sometimes striking; in France they were collected into a book titled, Astéroïde Hurlant, which I suspect would have a decent shot of showing up around here under the current DDP/Humanoids deal, along with the rest of Megalex, truthfully.

But flip through those back issues. There's stuff by Chase co-creator Dan Curtis Johnson, art by Ryan Sook... and what other magazine would surrender 10 pages to Guy Davis for an extended homage to Jacques Tardi?

Transcontinental bolt of lightning indeed.

And they kept it pretty much synced, for a while. The English-language edition ran for 14 issues, until 2004, while the French iteration saw 12 issues, in much the same format -- pamphlet-sized, initially thicker -- with similar (but not identical) content. The two series were released on a like minded schedule, and collapsed at roughly the same time; a 96-page special issue of the French edition emerged in 2006, apparently as a means of burning off some of the later stuff that appeared in only the English version, although there was some original content too.

It's fascinating to read through the stuff again today; Humanoids obviously saw the series as its bold flagship, and a forum for all sorts of promotion and personality. Editorials by publisher Fabrice Giger and managing editor Paul Benjamin are charmingly uninhibited and just a little pretentious, prone to colorful metaphors (Giger on transcontinental publishing: "the sword is heavy and hard to handle"), dramatic political exhortations (dated November 3, 2004: "in my dreams, the good guys always end up vanquishing the bad guys; I wish that in four years it would be a reality") and old-timey Team Comics fist-pumping for the good works done by Our Fellow Travelers at Fantagraphics, Image, Top Shelf, etc. - even Marvel, but don't be a superhero zombie, fanboy/girl!

There was a publicity motive at work too, naturally - the differences between the English and French editions seem to have been guided by what Humanoids wanted to promote in North America, in terms of authors, genres and formats. A Travis Charest Metabarons story would not run in the English Hurlant if it could be better sold as part of a Prestige Format one-shot like The Metabarons: Alpha/Omega. Sometimes projects would be announced, only to fade from view - did you know Humanoids planned to release Milo Manara's Giuseppe Bergman in North America (presumably 2004's The Odyssey of Giuseppe Bergman, since that's all Humanoïdes had published of the series at that time)?

I have to wonder if the imminent DC deal didn't scuttle that plan; the DC/Humanoids books may have undone the editing-for-content that went on in Humanoids' pamphlets, but I suspect DC may have been reluctant to take on such overtly sexual material.

Interestingly, Métal Hurlant never displayed the DC logo or listed DC personnel in on its masthead, even after the DC/Humanoids partnership began and the series started appearing with DC's solicitations. Perhaps something had to be left to Humanoïdes; an effort was made to preserve the new Hurlant's continuity with its ancestor, from the French edition maintaining the original issue numbering (it started with #134) to the English edition trumpeting issue #10's return of Richard Corben, surely the first great example of Hurlant's international eye. That was also the issue to announce the DC/Humanoids partnership, prompting publisher Giger to pronounce the series, four subsequent issues from evaporation, as "comics without borders."

Yet some boundaries couldn't be denied. My favorite thing in the revived Hurlant was a regular column by Humanoïdes co-founder Jean-Pierre Dionnet, who served as EiC of the old Hurlant for most of its existence and wrote a similar column in apparently every issue. Of the 'creatives' involved in the birth of Humanoïdes, Dionnet is easily the most obscure; he was a writer, but not an artist, and the only translated work of his that springs readily to mind is a 1977 Heavy Metal feature and subsequent book collection, Conquering Armies, a suite of sometimes-fantastical stories about mighty forces becoming somehow undermined, drawn in a shadowed heavy realist style by the late Jean-Claude Gal.

The guy wrote a good column, though, very much a blog-style point-by-point "what I'm reading-watching just now" kinda thing, ping-ponging from Kazuo Umezu to Lili St. Cyr to the dvd releases of Lobster Films to Avatar comics to Frédéric Coche to seemingly half of the U.S. mid-century pin-up/advertising art collections published between 2002 and 2004. Few language barriers were acknowledged, and Bud Plant was oft-toasted. At one point he mentions preparing for a project with Warren Ellis (the first and last I've heard of that) by reading through the man's complete works - an obsessive after my own heart!

But Dionnet also brought his acknowledged biases to the table, and refused to mince words. In his first column, he reflected on having difficulty coping with the story-first comics aesthetic of acclaimed works written by Alan Moore and the like, in that his own approach to comics had typically favored the promotion of splendid visuals as facilitated by script. If you're going to interface with North American comics, I think you have to acknowledge the minority status of that perspective, and only after a while can Dionnet (himself a writer, remember) understand the possible facility of visuals as supplicant to writing, even if the visuals themselves seem distinctly unexciting. And Dionnet didn't waste time puzzling over the C-list either; we're talking Steve Dillon on Preacher ("hideous") and J.H. Williams III on Promethea ("hippy art nouveau overflows"), the latter comment landing in the very same issue where Williams illustrates a Alejandro Jodorowsky short. J'accuse!

I think that kind of perspective is valuable, though, and probably not unexpected from the guy who edited Moebius & Druillet in their prime. You need only look at an early issue of Heavy Metal to see these values in full force, not that Dionnet was thrilled with what the American magazine became: "a drooling esthetic, falsely poetic and truly cheesy in a way that reminded me of black velvet paintings, with flying horses and sterile images of bimbos with perfect hairdos." It really was mostly a positive and enthusiastic column, though!

Dionnet was very enthusiastic about Jodorowsky too, and no doubt simpatico with his artist-first method of comics creation. And indeed, it's often easy to watch Jodorowsky's work rise and fall on the strength of his visual collaborators.

***

Bouncer: Raising Cain

For example, this book sees Jodorowsky teamed with a genuinely excellent artist, François Boucq. Like Moebius, Boucq is a notable writer/artist, although nothing of his solo work has been released in North America beyond Catalan Communications' 1989 edition of Pioneers of the Human Adventure, a fine, small collection of archly surreal social commentaries from the pages of (À Suivre). Catalan also released two of Boucq's funny, eccentric collaborations with writer Jerome Chayrin: The Magician's Wife, winner of the Best Comic Book prize at Angoulême in 1986, and Billy Budd, KGB. Boucq also won the Grand Prix de la ville d'Angoulême in 1998 for his cumulative body of work, so he has no lack of respect on the French scene.

For our purposes here, I'll also concede that Boucq strikes me as the ideal collaborator for Jodorowsky, even more so than Moebius. He has a wonderfully fleshy, molded approach to character art, with a keen eye for costuming and a great sense of comedy, typically pitting his soft-looking humans against disconcertingly realistic animals and detailed, evocative environments. Who better to convey the longing for sensitivity and oddball sexuality redolent in Jodorowsky's characters? Two people kissing seems like an oddly hilarious clash between the primal forces of the Earth to Boucq, which is naturally conductive to the archetype-driven action of Jodorowsky's plots - and he can do fantasy too!

Bouncer is the most recent collaboration between the two, a Western-as-in-gunfighters project begun in 2001 and currently up to vol. 6 in France; this sole DC/Humanoids book collects the first two French volumes, which appear to complete the series' initial storyline.

It's a good work, likely just the thing Kim Thompson had in mind when he cited the French comics industry for its 'crap': "that bulwark of solid, unpretentious, accessible genre fiction - a more or less undistinguished mass of okay-to-good comics that might catch your eye and give you a thrill, that loyal fans would buy out of habit, and anyone else might just pick up for the hell of it." If the Western were at all a viable genre in North American comics -- and, by and large, it's not -- this wouldn't be a bad piece to employ as a model for how to get it done.

Granted, it's still chock-full of Jodorowsky's writerly concerns, particularly his constant focus on the family. A solid 1/3 or so of the book is taken up by flashbacks explaining how the titular employee of the joyous-looking Inferno Saloon became a haunted man of violence - his mother was a child of rape and an adolescent prostitute who forged herself a place in a brutally masculine society, with the eventual, brutal aid of her three sons. But her greed and ambition eventually led them to knock over a steam engine ferrying the legendary and very subtly named Eye of Cain diamond, which eventually causes them all to go bonkers while in hiding; it's definitely more Treasure of the Sierra Madre than El Topo.

Brother inevitably turns against brother - one loses an arm, one loses and eye and the third loses his steel. Mother is so horrified with this breach of the family unit that she hangs herself, but only after hiding the diamond, prompting the one-eyed brother to slice her belly open and dig through her entrails for the treasure, which I know from experience tends to cause rifts between siblings. The not-physically-maimed brother leaves to find god and father a child with an Indian woman, but the end of the Civil War brings the return of his one-eyed counterpart, now leading a faction of bandits who refuse to acknowledge the Confederacy's surrender and hungrier than ever to find that lost diamond, which could power his force for years. Hidden under the floorboards, the child is baptized in the spilled blood of his murdered parents, and sets off to find his one-armed uncle, the Bouncer.

And while none of this gives Boucq quite the best chance to show off the fleshy-surreal side of his style -- even a Peyote-powered hallucination sequence comes off as distinctly grounded -- his sun-baked colors do effectively mute the romance of blood and dust into a parched, dirty struggle between fundamentally pliable humans. Everybody is sort of wrinkled and gross, even the 'beautiful' women, which does scratch at the shared humanity suggested by Jodorowsky's backdrop of racism and political-minded brutality.

It also kind of offsets the writer's taste for cross-genre cheese, which does coexist with the period verisimilitude. For all its attempts at suggesting departures from stereotypical femininity, this is a Jodorowsky story, and thus a work of archetypes questing. There's several Garth Ennis-like reflections on fabulous killing as a defining masculine trait, capped off with an eye-rolling moment in which the Bouncer's nephew completes his training-for-revenge and takes a bath, only for a nearby woman to comment on how large his prick is. It's the kind of book where an enlightened new schoolmarm from out of town raises a ruckus with her liberal ideas about Native treatment, but still sets several pages aside for the comedy stylings of a drunken Injun sputtering pidgin English.

Let's hope you're also ready for some high melodrama, the sort that assures Our Young Hero's burgeoning romance with a young lady cannot pass without remark from the familial theme. That part seems a little more fitting, though, small as it makes the Old West seem; even the worst, most murderous villain is ultimately reduced to a child in the end, in spite of all macho activity, shouting at Mommy while longing after her forgiveness. You'll find some escape from that motif in Jodorowsky's work, but not much; even his 'small' works like this are stained with trauma, although littler stories offer less a full-scale enlightenment for their characters than a modest possibility of grace. At least the world itself seems especially responsive here.

***

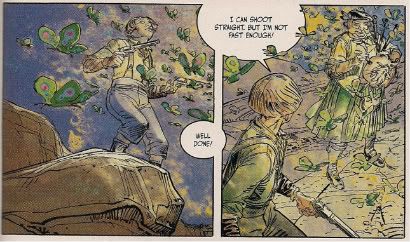

Megalex Vol 1: The Anomaly

And on the flip side of responsiveness and (relative) modesty, we have Megalex, which Humanoids positioned as the first 'major' serial of the revived Metal Hurlant; the second was Fragile, which did not finish before Hurlant sank, although the DC/Humanoids collected edition restores all missing chapters.

'Serial' is a tricky term, of course. As far as I know, the three-volume Megalex (1999-2008) behaved as your typical direct-to-album release in Europe; it wasn't even part of the French edition of Hurlant, leading me to guess that Humanoids made an educated guess that what Direct Market readers would really like to see in a new anthology was more Jodorowsky, and, Jean-Pierre Dionnet's black velvet assertions notwithstanding, a big ol' bunch of hot hot CGI ladies with improbably enormous breasts. And since the third volume wasn't even close to finished at the time, the adventure simply stopped at the end of the French vol. 2, which is as far as the DC/Humanoids collection goes as well.

I wonder if this series had anything to do with La Guerre de Megamex (The War of Megamex), a project Jodorowsky had intended to begin with Akira creator Katsuhiro Ōtomo in the early '90s - surely Megalex's city vistas and sprawling melee action seem keyed to Ōtomo's particular East-West blend of comics maximalism. Tragically, we don't have Ōtomo on hand for this one. We have Fred Beltran.

Beltran, you'll remember, is the guy who devised the updated color scheme for the 'new' versions of The Incal and its prequels. He also worked directly with Zoran Janjetov to create the super-shiny digital look of The Technopriests. This is apparently his first work with Jodorowsky as sole artist, and he rightly seizes the opportunity to attempt the annihilation of the human trace altogether by posing 3D models inside a a wholly CGI environment - Batman: Digital Justice, eat your heart out!

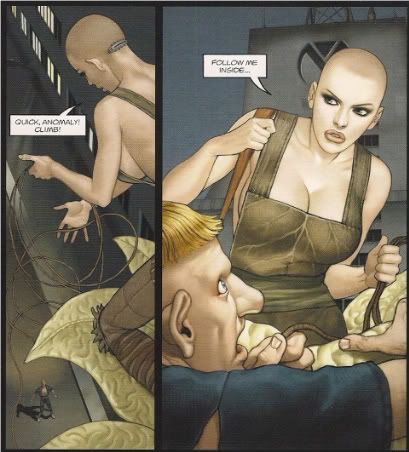

And while I'll readily admit that Beltran's 3D modeling is better than average -- and do note that vol. 3 seem to pursue a different style entirely -- it still doesn't hold much appeal at all to me. Jodorowsky's plot is among his most off-the-cuff in feel, positing a future civilization where drug addiction is mandatory and labor is forbidden, and every atrocity imaginable is processed into entertainment for the lazy populace - it's basically those five or six bits in the Incal with everyone watching the action on tv, stretched well beyond the breaking point into an entire series.

Banalities and contrivances pile - a strange attack on the city leaves an assembly line police clone overgrown and awkward (nonconformity!), mandating his escape from society into the oddball confederation of (literally) underground mutant rebels who desire to topple the city with the sleeping might of nature: giant roots and talking lizards and the like. But Beltran's art is entirely unsuccessful at portraying anything 'natural' without it looking dug out from a plastic cast; while I suspect the 'off the assembly line' nature of the city's robots and cloned citizens were supposed to play to Beltran's strengths, it's nonetheless puzzling how an earth vs. tech plot like this even wound up with an all-CG artist whose talents are almost entirely predisposed toward the antagonistic 'tech' side of things.

Or maybe that's foreshadowing? I don't know, but Beltran's eventual, not-in-this-book switch in visual approach suggests otherwise.

At least Beltran does manage the perverse flourish of basing every last female character, from the obligatory cruel mother figure to all the various love interests, off of the same woman, his own wife - Jodorowsky must have appreciated that!

Likewise, some of the writer's odder ideas -- a sad, wicked princess whose longing for intimacy is always ruined by her aptitude for immolating anyone who touches her skin, a labyrinth master named Cabot-Chadday (who may be a pair of twins, or possibly just one guy and an imaginary friend) who fathered the mutants with a talking wolf he insists is a beautiful woman, a tribal contest of champions that plays out in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome piggyback battle royale fashion -- congeal into some effective distraction, but there's no salvaging the whole (er, 2/3 of a whole) from its patent disconnect of presentation and content.

Even the pacing seems spoiled by the art, with nearly all of the French vol. 1 (i.e. the first half of the U.S. book) functioning as a chase scene through Beltran's computer backgrounds, and vol. 2 (for which I expect the technology was supposed to improve) split into piles of tiny panels populated by half-expressive characters for the purpose of dumping out the necessary plot. It's a mess, but a telling one - just try and think of exactly the same content drawn by a Katsuhiro Ōtomo, and you can all but see the improvement.

It's too bad - the revived Hurlant did sport some decent-looking pieces during its short life, and the quality was generally a lot higher than that of the still-enduring Heavy Metal. Jodorowsky's short stories with the likes of J.H. Williams III and José Ladrönn were often cutesy but sometimes striking; in France they were collected into a book titled, Astéroïde Hurlant, which I suspect would have a decent shot of showing up around here under the current DDP/Humanoids deal, along with the rest of Megalex, truthfully.

But flip through those back issues. There's stuff by Chase co-creator Dan Curtis Johnson, art by Ryan Sook... and what other magazine would surrender 10 pages to Guy Davis for an extended homage to Jacques Tardi?

Transcontinental bolt of lightning indeed.

Labels: Hurlant

<< Home