Désastre Hurlant (T6): La Constellation

"You cannot get to know a flower by tearing its petals. It’s a sad analytic point of view. You get to know a flower by enjoying it."

- Jodorowsky, to Matt Brady, 2001

***

The Incal

(collected by DC/Humanoids as The Incal Vol. 1: The Epic Conspiracy & The Incal Vol. 2: The Epic Journey; reviewed and excerpted from the three-volume Epic/Marvel edition, 1988)

Aw, but Lewis - this one's got its charms!

And it ought to, right? I mean, The Incal may not have quite indelibly stamped itself upon the public consciousness following its most recent, two-book publication at the 2005 tail end of the DC/Humanoids deal, but there's little denying it's a signature work on the part of its creators, writer Alejandro Jodorowsky and artist Moebius. Indeed, its six-album expanse, originally released between 1980 and 1988, forms the very core of Jodorowsky's extensive shared universe of comics, populated by the likes of the probably-more-popular-around-these-parts saga of The Metabarons, from the brush of Juan Giménez.

Hell, one could even argue that Jodorowsky wouldn't be known at all today as a comic book writer had it not been for that particular series, but it's nonetheless important not to overstate the work's originality, I think, since it occupies a very unique place in the oeuvres of both authors, and is best appreciated as a particular collision of developing forces, a dark crystal and a light crystal combining to form a starship readied to shrink into folks' pores or expand so large as to house the dreams of galaxies. As the plot goes.

The Incal was not Jodorowsky's first comic, nor even his first comic with Moebius; he'd actually been been writing (and sometimes drawing) pieces in Mexico since the mid-'60s as a corollary to his work with the Panic Movement, an art collective he'd founded in Paris with, among other devotees of Pan, novelist & comics artist Roland Topor, who'd later contribute to the French humor magazine Hara-Kiri around the same time that 'Moebius' began to develop apart from Jean Giraud, in those same pages. Both Topor and Moebius would later associate with the animator René Laloux in separate motion pictures: 1973's Fantastic Planet and 1981's Time Masters. Jodorowsky would have already directed three features by the time Moebius co-founded Les Humanoïdes Associés in 1974.

But it'd be Jean Giraud's Blueberry that initially attracted Jodorowsky, prompting him to hire the artist to contribute storyboards and designs to a planned movie adaptation of Dune, a massive undertaking that was to involve the likes of H.R. Giger, Dan O'Bannon, Orson Welles, Pink Floyd and Salvador Dalí in various capacities, until the whole thing toppled over from lack of funding in 1976. Moebius would later contribute with Giger and O'Bannon to a different picture, 1979's Alien, but Jodorowsky got the idea that the two of them should work together in comics; the initial result was 1978's Eyes of the Cat, a digest-sized giveaway comic matching lavishly alien, Arzach-type visuals (albeit in b&w) with a minimal text narration, Moebius very much up front.

That made sense, as the artist was right in the midst of an especially striking period. He was busy putting together his magnum opus of poetic improvisation, The Airtight Garage (then still of Jerry Cornelius), while fresh off the puzzling lyricism of Arzach and the influential 'dirty future' stylings of The Long Tomorrow (written by the aforementioned O'Bannon), and other works hot from the launch of Métal Hurlant. As Jodorowsky mused to Stephen R. Bissette in Taboo Vol. 4, where The Eyes of the Cat was first presented in English:

"Because Moebius is a self-sufficient talent, he doesn't need to give half of the work, half of the money to me: we split what we do. If he doesn't like the story, he could write his own [stories].... Well, with this story, he realized that he could change himself also. His work did change, after that."

Their next project was The Incal, and it was indeed a type of departure, if also a return to certain things at the same time. Many of the ideas Jodorowsky had been cooking up for the Dune movie found their way into the comic; signs point to it maybe not having threatened to develop into a terribly close adaptation, especially given that Jodorowsky had signed on to direct having not actually read the book, but instead having been captivated by hearing someone describe the book to him.

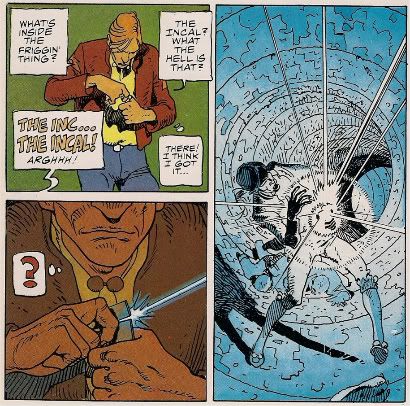

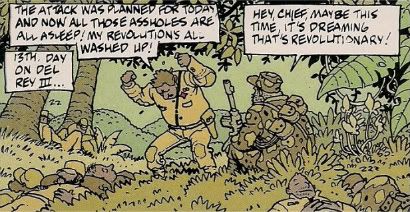

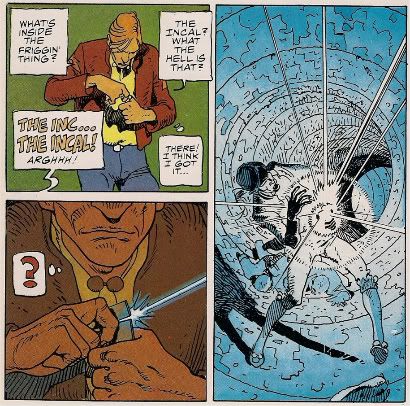

Additionally, Moebius almost directly revisited the grimy sci-fi noir of the Long Tomorrow in the Incal's early pages, in which piece-of-shit 'Class-B' private investigator John DiFool guides a lousy halo-wearing 'aristo' dame from the upper levels of his very Metropolis-styled future urban region through the Crimson Circle and winds up laying hands on the titular mystic triangle via a poor mutant mug with a blade in his back. Perhaps some admirers of the Airtight Garage would appreciated the amusing survey of interested parties teeming and scheming around detailed environments in the developments that followed.

But the trick is, while the Incal is like those other works, it's not really like them. The Airtight Garage was an exercise in unwavering seat-of-the-pants narrative digression, twisting anew with the start of each new two or five-page chapter and adding up to a crystalline, nearly inscrutable work of poetic-parodic-generic artificial worldbuilding. And the Long Tomorrow was literally a joke, a tongue-clucking transposition of brutish, misogynistic noir tropes onto a rocket-powered sci-fi landscape, the kind of thing that somehow seems overlong at only a dozen or so pages yet nonetheless spawns all sorts of far more serious takes on the same general notion.

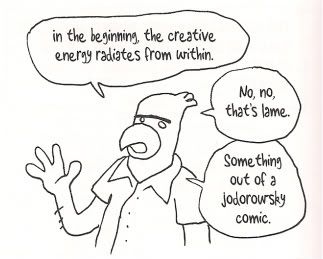

With Jodorowsky as his partner, Moebius suddenly found himself organized into a far more typical, comedic-but-also-serious sprawling adventure narrative, the sort of thing he'd avoided since taking on the 'Moebius' name and setting up an alternate style - another return to the past! Interestingly, this came about from a rather freewheeling creative give-and-take, with Jodorowsky declining to write a script in favor of acting out the story in front of Moebius, who'd scratch out page layouts on the spot, pausing sometimes to interject his own opinions on Jodorowsky's performance (remember folks, he's a trained mime!). The two would only hash out the dialogue after the images were settled, so as to ensure a tighter, responsive relationship between words and pictures.

Given all that, I can only conclude that Jodorowsky's obsession with archetypes and spiritual quest navigation, of which more will be mentioned later, are more favorably disposed toward linearity, with many half-magical 'soft' sci-fi ideas blending into a propulsive adventure narrative, a real bubblegum crisis plot, in which a small problem grows bigger and bigger and bigger, expanding until the entire future of human and alien lifeforms is on the line.

It's like the Moebius comic for people who'd sort of hoped Moebius would get around to doing more straight-on action work, loaded with explosions and fights, setting his uncanny grasp of spaces to evoke immediate wonder and awe in a less esoteric discovery context.

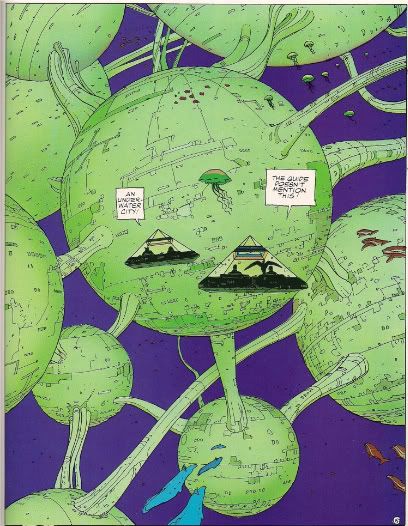

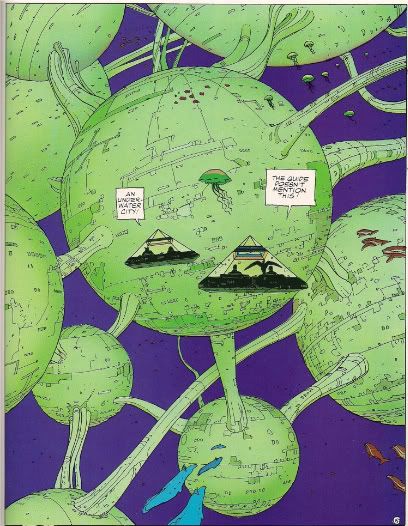

It really works, though. Moebius draws good action pages, keeping the reader perfectly on the level while whipping up panel after panel of crowded activity - his influence on the likes of Geof Darrow is never clearer than through those early urban action pages! Yet he also knows just when to pull back and relieve some visual tension, aided by a fine crew of colorists including Yves Chaland -- soon to be a very acclaimed cartoonist in his own right -- and future Incal prequel artist Zoran Janjetov, who'd become a regular Jodorowsky cohort.

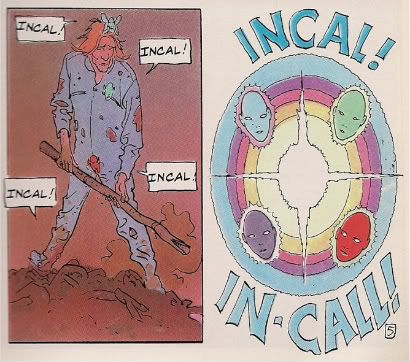

There's also a certain fragility to Moebius' drawings, especially his character work, cartooned in a manner that suggests half a mind perpetually toward humor, in the way an American 'underground' cartoonist of the '60s might evoke a genre work. Nothing is off the table, be it surprise lines leaping from the head of Deepo, DiFool's talking Concrete Parrot pet, or utterly disarming graphic flourishes that wouldn't seem out of place in a superhero comic from 15 years prior.

Indeed, in the back of the final volume of the 1988 Epic-Marvel release of the material, Moebius (who'd soon be working on a Silver Surfer story with Stan Lee) cops to leafing through a pile of his son's American comic books for inspiration as the story went on, declaring that even the bad artwork sometimes suggested an interesting approach underneath poor execution.

And the art noticeably changes as the chapters pass by - each of the French volumes is marked by certain organizational motifs, with horizontal movements in the first two albums switching to a horizontal emphasis for the next pair, the third moving top-to-bottom and the fourth going bottom-to-top, to show the evolution of the characters to galactic heroes after their descent into the core of the tiered civilization of earlier pages, though the descent itself is a discovery. The fifth and sixth albums were initially intended as one fat volume (both were released in 1988), and their plunge into the core of human being finds Moebius' panels suddenly overlapping one another and contorting into many dynamic shapes to better convey the struggle.

But wait - the core of human being? Ascension to the stars?

That's the presence of Jodorowsky, whose most popular films -- 1970's El Topo and 1973's The Holy Mountain -- also ensconed spiritual quests in genre happenings, westerns and interplanetary sci-fi, never hiding the fact that the real goal is to arrive at some personal awakened state. Perhaps we can explain the Incal's big, brawny, action-packed bombast as a desire to strike back at the limitations that flattened Dune, to manifest a film-on-paper that never needs to slow down, that just keeps throwing situations and visions and encounters at the reader/viewer. But it also shares the urgency of purification with those cinema works.

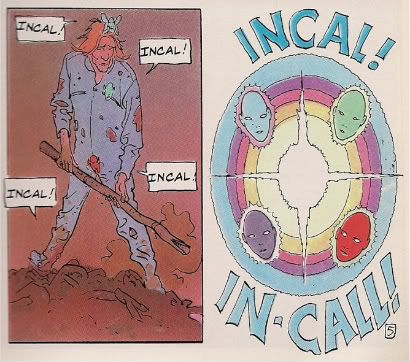

The Incal is also deeply connected to the tarot, which Jodorowsky understands as a "nomadic cathedral," a structure dually representational of the human and the divine. John DiFool is, unsurprisingly, the Fool, the sometimes unnumbered card and the classical protagonist of the Fool's Journey through the temple and all the stars, each card a point in the constellation. The Fool is often illustrated as approaching a cliff, so Jodorowsky naturally begins his story by chucking DiFool right off.

And of course, the dog seen nipping at the Fool's heels is transformed into a talking sci-fi bird - this is comics! This is adventure! I do get the impression that Jodorowsky paused and smiled before each and every sequence of a hero held captive by a talkative, sneering villain (there's many) and assured himself -- and possibly Moebius, who'd be sitting right there -- that this is what comics are like.

It's certainly no orderly journey for DiFool. Tarot signposts aren't so much encountered as thrust together, sometimes literally, as in the case of the Emperoratrix, ruler of the galaxy and conjoined male-female twins stuck in a womb. There's also a female love interest, subtly named Animah, the mother of DiFool's illegitimate androgyne child Sunmoon, who takes the Light Incal of his father and the Dark Incal of his mother and forms a Star Ship, embodying all three celestial-scientific bodies of the Major Arcana in one amazing value.

Truthfully, Jodorowsky is more at ease with archetypes and representations than full-bodied characters, much in the way his narrative is concerned more with piling on bigger and bolder threats and puzzles than delving particularly deep into 'literary' values. DiFool encounters many characters, like the id devil Kill Wolfhead, and the ambitious former Incal guardian Tanatah, head of the rebel faction Amok (hey, as long as they don't Panic...), and, of course, the Metabaron, legendary warrior and tender soul. And while it wouldn't be fair to say these characters never change over the course of the story, their development is as simple and sudden as inverting a card.

But when I lean in to sniff this little rose, my impression is that Jodorowsky isn't so much concerned with making his story 'work' as laying out as many off-the-cuff metaphors for human betterment as he can, through all the popular and esoteric images/symbols at his brow. It can be good loopy fun, but also tedious, particularly when its genre mechanisms click into Manichean conflicts between Our Sometimes Reluctant Heroes and the underdetailed pawns of the Great Darkness that eventually threatens all of universal life. Often the writer swings the Incal like a truncheon, his symbol of humankind's potential for grace acting as an all-purpose conflict solver and narrative engine, sometimes overtly dictating where the story ought to go, in lieu of anything more organic.

Yet there are also effective passages, always aided by Moebius' little touches, like the way he keeps DiFool's body a little bit in flux, drawing him as more handsome when the Incal is close to him. There's a nice part where everyone first enters their Not Yet a Star Ship, the seven of them (good number, the number of God, the Chariot in the tarot, victory and will) knowing exactly where to position themselves in relation to their metaphoric weights and personal relationships - psychomagical values, building spatial relationships so as to assess the rot of the family tree, complimenting the space of the tarot as architecture. As Animah would probably tell you, magic is psychology to Jodorowsky, and ritual is therapy.

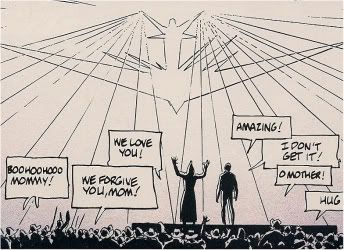

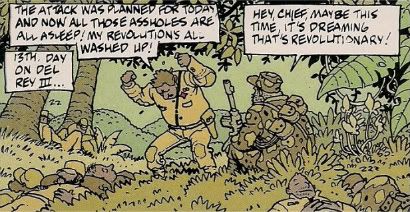

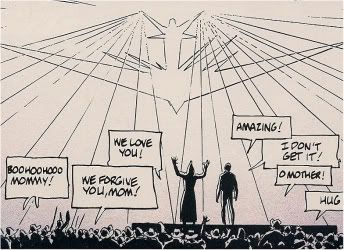

There's a crucial, long bit near the end where DiFool is sent to convince an entire planet's population to start dreaming, so as to combat the Great Darkness. Slowly, he discovers that a prior visit of his resulted in his spawning an entire population of male and female copies of himself from the planet's Protoqueen, all of whom are angry and upset because their mother doesn't love them, all because DiFool left her for Animah, a different type of mirroring: himself, really.

It's a deeply odd and not slightly simplistic setup, but it kind of shudders with sincere hurt, even as DiFool struggles to assure the arch-mother that she never really loved him as much as his potential anyway, and thus has no need to be cruel to her children, since all of them (and her) carry the same sublime beauty. Everyone falls over with love; everyone makes up with their mother. It's unashamed and oh it stings of salt.

I expect this is what readers responded to from the Incal, besides the whole appeal of 300 pages of Moebius art: a man really putting himself out there in his sci-fi, making it pulse with ideas. This comic can be tiresome, or clumsy, but nothing, absolutely nothing seems affected or calibrated for anything other than personal expression through popular mechanics; a real joy runs through it, from laying hands on all that awesome-ridiculous sci-fi shit and trying to stack it all as high as possible, sophistication be damned.

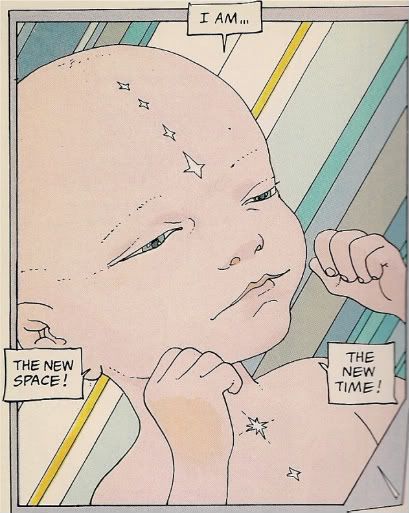

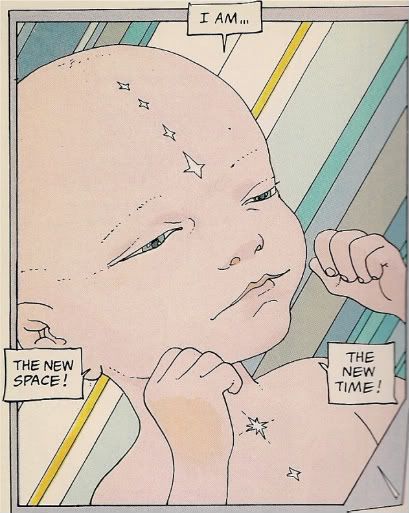

Its finale sees things through the only way it can, with DiFool breaking through to the center of things and discovering that, naturally, the darkness and the light are within each person, and we can be our own gods if we want, the spark that forms the new reality, etc. And, amusingly, DiFool is left behind to witness while everyone else is absorbed, and cast back to the beginning of the story to remember the lessons he's learned, falling off another ledge, starting another reading. What, you thought a comic would revolutionize the world on its own?!

That's the Jodorowsky way. El Topo winds up immolating himself over the bottomless cruelty of humankind, leaving his son to ride away with his burden of identity. And god knows the final revelation upon the Holy Mountain is that cinema is but a construct, a mime and fable, viewable as such upon a crucial pull back. As such, the Incal -- the realization of Dune's various potentials -- is like the final installment of a trilogy of circles, overlapping a bit in obsessions, urging you witness its lessons.

The writer would grow less timid later on. He would come to perform actual psychomagic rituals on people, as his comics work honed in on characters or clans, tracking their activities in a somewhat more attached manner. He'd write several Incal prequels and sequels, exactly one of which would involve Moebius' participation in the manner of drawing things. I wonder how Final Incal is supposed to operate? All the cards are numbered now, out of order, more or less. That's all right; the deck needs to be shuffled. The tools were assembled in '88. From there on, it was a matter of using them.

- Jodorowsky, to Matt Brady, 2001

***

The Incal

(collected by DC/Humanoids as The Incal Vol. 1: The Epic Conspiracy & The Incal Vol. 2: The Epic Journey; reviewed and excerpted from the three-volume Epic/Marvel edition, 1988)

Aw, but Lewis - this one's got its charms!

And it ought to, right? I mean, The Incal may not have quite indelibly stamped itself upon the public consciousness following its most recent, two-book publication at the 2005 tail end of the DC/Humanoids deal, but there's little denying it's a signature work on the part of its creators, writer Alejandro Jodorowsky and artist Moebius. Indeed, its six-album expanse, originally released between 1980 and 1988, forms the very core of Jodorowsky's extensive shared universe of comics, populated by the likes of the probably-more-popular-around-these-parts saga of The Metabarons, from the brush of Juan Giménez.

Hell, one could even argue that Jodorowsky wouldn't be known at all today as a comic book writer had it not been for that particular series, but it's nonetheless important not to overstate the work's originality, I think, since it occupies a very unique place in the oeuvres of both authors, and is best appreciated as a particular collision of developing forces, a dark crystal and a light crystal combining to form a starship readied to shrink into folks' pores or expand so large as to house the dreams of galaxies. As the plot goes.

The Incal was not Jodorowsky's first comic, nor even his first comic with Moebius; he'd actually been been writing (and sometimes drawing) pieces in Mexico since the mid-'60s as a corollary to his work with the Panic Movement, an art collective he'd founded in Paris with, among other devotees of Pan, novelist & comics artist Roland Topor, who'd later contribute to the French humor magazine Hara-Kiri around the same time that 'Moebius' began to develop apart from Jean Giraud, in those same pages. Both Topor and Moebius would later associate with the animator René Laloux in separate motion pictures: 1973's Fantastic Planet and 1981's Time Masters. Jodorowsky would have already directed three features by the time Moebius co-founded Les Humanoïdes Associés in 1974.

But it'd be Jean Giraud's Blueberry that initially attracted Jodorowsky, prompting him to hire the artist to contribute storyboards and designs to a planned movie adaptation of Dune, a massive undertaking that was to involve the likes of H.R. Giger, Dan O'Bannon, Orson Welles, Pink Floyd and Salvador Dalí in various capacities, until the whole thing toppled over from lack of funding in 1976. Moebius would later contribute with Giger and O'Bannon to a different picture, 1979's Alien, but Jodorowsky got the idea that the two of them should work together in comics; the initial result was 1978's Eyes of the Cat, a digest-sized giveaway comic matching lavishly alien, Arzach-type visuals (albeit in b&w) with a minimal text narration, Moebius very much up front.

That made sense, as the artist was right in the midst of an especially striking period. He was busy putting together his magnum opus of poetic improvisation, The Airtight Garage (then still of Jerry Cornelius), while fresh off the puzzling lyricism of Arzach and the influential 'dirty future' stylings of The Long Tomorrow (written by the aforementioned O'Bannon), and other works hot from the launch of Métal Hurlant. As Jodorowsky mused to Stephen R. Bissette in Taboo Vol. 4, where The Eyes of the Cat was first presented in English:

"Because Moebius is a self-sufficient talent, he doesn't need to give half of the work, half of the money to me: we split what we do. If he doesn't like the story, he could write his own [stories].... Well, with this story, he realized that he could change himself also. His work did change, after that."

Their next project was The Incal, and it was indeed a type of departure, if also a return to certain things at the same time. Many of the ideas Jodorowsky had been cooking up for the Dune movie found their way into the comic; signs point to it maybe not having threatened to develop into a terribly close adaptation, especially given that Jodorowsky had signed on to direct having not actually read the book, but instead having been captivated by hearing someone describe the book to him.

Additionally, Moebius almost directly revisited the grimy sci-fi noir of the Long Tomorrow in the Incal's early pages, in which piece-of-shit 'Class-B' private investigator John DiFool guides a lousy halo-wearing 'aristo' dame from the upper levels of his very Metropolis-styled future urban region through the Crimson Circle and winds up laying hands on the titular mystic triangle via a poor mutant mug with a blade in his back. Perhaps some admirers of the Airtight Garage would appreciated the amusing survey of interested parties teeming and scheming around detailed environments in the developments that followed.

But the trick is, while the Incal is like those other works, it's not really like them. The Airtight Garage was an exercise in unwavering seat-of-the-pants narrative digression, twisting anew with the start of each new two or five-page chapter and adding up to a crystalline, nearly inscrutable work of poetic-parodic-generic artificial worldbuilding. And the Long Tomorrow was literally a joke, a tongue-clucking transposition of brutish, misogynistic noir tropes onto a rocket-powered sci-fi landscape, the kind of thing that somehow seems overlong at only a dozen or so pages yet nonetheless spawns all sorts of far more serious takes on the same general notion.

With Jodorowsky as his partner, Moebius suddenly found himself organized into a far more typical, comedic-but-also-serious sprawling adventure narrative, the sort of thing he'd avoided since taking on the 'Moebius' name and setting up an alternate style - another return to the past! Interestingly, this came about from a rather freewheeling creative give-and-take, with Jodorowsky declining to write a script in favor of acting out the story in front of Moebius, who'd scratch out page layouts on the spot, pausing sometimes to interject his own opinions on Jodorowsky's performance (remember folks, he's a trained mime!). The two would only hash out the dialogue after the images were settled, so as to ensure a tighter, responsive relationship between words and pictures.

Given all that, I can only conclude that Jodorowsky's obsession with archetypes and spiritual quest navigation, of which more will be mentioned later, are more favorably disposed toward linearity, with many half-magical 'soft' sci-fi ideas blending into a propulsive adventure narrative, a real bubblegum crisis plot, in which a small problem grows bigger and bigger and bigger, expanding until the entire future of human and alien lifeforms is on the line.

It's like the Moebius comic for people who'd sort of hoped Moebius would get around to doing more straight-on action work, loaded with explosions and fights, setting his uncanny grasp of spaces to evoke immediate wonder and awe in a less esoteric discovery context.

It really works, though. Moebius draws good action pages, keeping the reader perfectly on the level while whipping up panel after panel of crowded activity - his influence on the likes of Geof Darrow is never clearer than through those early urban action pages! Yet he also knows just when to pull back and relieve some visual tension, aided by a fine crew of colorists including Yves Chaland -- soon to be a very acclaimed cartoonist in his own right -- and future Incal prequel artist Zoran Janjetov, who'd become a regular Jodorowsky cohort.

There's also a certain fragility to Moebius' drawings, especially his character work, cartooned in a manner that suggests half a mind perpetually toward humor, in the way an American 'underground' cartoonist of the '60s might evoke a genre work. Nothing is off the table, be it surprise lines leaping from the head of Deepo, DiFool's talking Concrete Parrot pet, or utterly disarming graphic flourishes that wouldn't seem out of place in a superhero comic from 15 years prior.

Indeed, in the back of the final volume of the 1988 Epic-Marvel release of the material, Moebius (who'd soon be working on a Silver Surfer story with Stan Lee) cops to leafing through a pile of his son's American comic books for inspiration as the story went on, declaring that even the bad artwork sometimes suggested an interesting approach underneath poor execution.

And the art noticeably changes as the chapters pass by - each of the French volumes is marked by certain organizational motifs, with horizontal movements in the first two albums switching to a horizontal emphasis for the next pair, the third moving top-to-bottom and the fourth going bottom-to-top, to show the evolution of the characters to galactic heroes after their descent into the core of the tiered civilization of earlier pages, though the descent itself is a discovery. The fifth and sixth albums were initially intended as one fat volume (both were released in 1988), and their plunge into the core of human being finds Moebius' panels suddenly overlapping one another and contorting into many dynamic shapes to better convey the struggle.

But wait - the core of human being? Ascension to the stars?

That's the presence of Jodorowsky, whose most popular films -- 1970's El Topo and 1973's The Holy Mountain -- also ensconed spiritual quests in genre happenings, westerns and interplanetary sci-fi, never hiding the fact that the real goal is to arrive at some personal awakened state. Perhaps we can explain the Incal's big, brawny, action-packed bombast as a desire to strike back at the limitations that flattened Dune, to manifest a film-on-paper that never needs to slow down, that just keeps throwing situations and visions and encounters at the reader/viewer. But it also shares the urgency of purification with those cinema works.

The Incal is also deeply connected to the tarot, which Jodorowsky understands as a "nomadic cathedral," a structure dually representational of the human and the divine. John DiFool is, unsurprisingly, the Fool, the sometimes unnumbered card and the classical protagonist of the Fool's Journey through the temple and all the stars, each card a point in the constellation. The Fool is often illustrated as approaching a cliff, so Jodorowsky naturally begins his story by chucking DiFool right off.

And of course, the dog seen nipping at the Fool's heels is transformed into a talking sci-fi bird - this is comics! This is adventure! I do get the impression that Jodorowsky paused and smiled before each and every sequence of a hero held captive by a talkative, sneering villain (there's many) and assured himself -- and possibly Moebius, who'd be sitting right there -- that this is what comics are like.

It's certainly no orderly journey for DiFool. Tarot signposts aren't so much encountered as thrust together, sometimes literally, as in the case of the Emperoratrix, ruler of the galaxy and conjoined male-female twins stuck in a womb. There's also a female love interest, subtly named Animah, the mother of DiFool's illegitimate androgyne child Sunmoon, who takes the Light Incal of his father and the Dark Incal of his mother and forms a Star Ship, embodying all three celestial-scientific bodies of the Major Arcana in one amazing value.

Truthfully, Jodorowsky is more at ease with archetypes and representations than full-bodied characters, much in the way his narrative is concerned more with piling on bigger and bolder threats and puzzles than delving particularly deep into 'literary' values. DiFool encounters many characters, like the id devil Kill Wolfhead, and the ambitious former Incal guardian Tanatah, head of the rebel faction Amok (hey, as long as they don't Panic...), and, of course, the Metabaron, legendary warrior and tender soul. And while it wouldn't be fair to say these characters never change over the course of the story, their development is as simple and sudden as inverting a card.

But when I lean in to sniff this little rose, my impression is that Jodorowsky isn't so much concerned with making his story 'work' as laying out as many off-the-cuff metaphors for human betterment as he can, through all the popular and esoteric images/symbols at his brow. It can be good loopy fun, but also tedious, particularly when its genre mechanisms click into Manichean conflicts between Our Sometimes Reluctant Heroes and the underdetailed pawns of the Great Darkness that eventually threatens all of universal life. Often the writer swings the Incal like a truncheon, his symbol of humankind's potential for grace acting as an all-purpose conflict solver and narrative engine, sometimes overtly dictating where the story ought to go, in lieu of anything more organic.

Yet there are also effective passages, always aided by Moebius' little touches, like the way he keeps DiFool's body a little bit in flux, drawing him as more handsome when the Incal is close to him. There's a nice part where everyone first enters their Not Yet a Star Ship, the seven of them (good number, the number of God, the Chariot in the tarot, victory and will) knowing exactly where to position themselves in relation to their metaphoric weights and personal relationships - psychomagical values, building spatial relationships so as to assess the rot of the family tree, complimenting the space of the tarot as architecture. As Animah would probably tell you, magic is psychology to Jodorowsky, and ritual is therapy.

There's a crucial, long bit near the end where DiFool is sent to convince an entire planet's population to start dreaming, so as to combat the Great Darkness. Slowly, he discovers that a prior visit of his resulted in his spawning an entire population of male and female copies of himself from the planet's Protoqueen, all of whom are angry and upset because their mother doesn't love them, all because DiFool left her for Animah, a different type of mirroring: himself, really.

It's a deeply odd and not slightly simplistic setup, but it kind of shudders with sincere hurt, even as DiFool struggles to assure the arch-mother that she never really loved him as much as his potential anyway, and thus has no need to be cruel to her children, since all of them (and her) carry the same sublime beauty. Everyone falls over with love; everyone makes up with their mother. It's unashamed and oh it stings of salt.

I expect this is what readers responded to from the Incal, besides the whole appeal of 300 pages of Moebius art: a man really putting himself out there in his sci-fi, making it pulse with ideas. This comic can be tiresome, or clumsy, but nothing, absolutely nothing seems affected or calibrated for anything other than personal expression through popular mechanics; a real joy runs through it, from laying hands on all that awesome-ridiculous sci-fi shit and trying to stack it all as high as possible, sophistication be damned.

Its finale sees things through the only way it can, with DiFool breaking through to the center of things and discovering that, naturally, the darkness and the light are within each person, and we can be our own gods if we want, the spark that forms the new reality, etc. And, amusingly, DiFool is left behind to witness while everyone else is absorbed, and cast back to the beginning of the story to remember the lessons he's learned, falling off another ledge, starting another reading. What, you thought a comic would revolutionize the world on its own?!

That's the Jodorowsky way. El Topo winds up immolating himself over the bottomless cruelty of humankind, leaving his son to ride away with his burden of identity. And god knows the final revelation upon the Holy Mountain is that cinema is but a construct, a mime and fable, viewable as such upon a crucial pull back. As such, the Incal -- the realization of Dune's various potentials -- is like the final installment of a trilogy of circles, overlapping a bit in obsessions, urging you witness its lessons.

The writer would grow less timid later on. He would come to perform actual psychomagic rituals on people, as his comics work honed in on characters or clans, tracking their activities in a somewhat more attached manner. He'd write several Incal prequels and sequels, exactly one of which would involve Moebius' participation in the manner of drawing things. I wonder how Final Incal is supposed to operate? All the cards are numbered now, out of order, more or less. That's all right; the deck needs to be shuffled. The tools were assembled in '88. From there on, it was a matter of using them.

Labels: Hurlant

<< Home