"HA HA HA HA HA HA!!!... I'VE EVOLVED INTO CINDERS FROM THE COSMOS!!"

Where Demented Wented: The Art and Comics of Rory Hayes

The quote above isn't anything Rory Hayes put in a comic. His writing doesn't quote well, prone to grammar errors and flat declaration as it is, a cadence burnt into the brain from old horrors, movies and comics, condensed and whittled into the stuff of ready recollection. There seems to be no filter.

No, all of those caps come from something Hayes said, as recorded in Bill Griffith's utterly beautiful tribute to Hayes, a two-page comic from 1980, depicting its still-young subject walking through a rainstorm on the third evening of his latest pharmaceutical binge, clutching his beloved, talking teddy bear character Pooh Rass in his arms and narrating his screenplay to the grand horror movie of his dreams, undeterred by the knife plunged into his chest and the blood soaking into his shirt. It would still be three years before Hayes died at 34, dead from drugs, still young.

Rory Hayes was an underground cartoonist in the late-'60s/early-'70s heyday of comix-with-an-x. You might call him an "artist's artist," in that his work was often unpopular with the underground readership, though Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, Griffith and others were among his admirers. And if you accept the dichotomy of the underground era as split between talents who loved EC's humor comics best -- the Crumbs and Spiegelmans and such -- and those who adored the horror and fantasy and mayhem -- Greg Irons, Richard Corben -- Hayes becomes oddly miraculous, in that his own tastes sat so clearly with the latter, yet his memory rests mainly in the renown of the former.

But memory, generic memory, critical memory, history, is so damn slippery, greasing our travel back in time until we move with such velocity that our surroundings seem no more than speed lines, our perceptions limited to what narratives we are already prone to recognizing from those sequential images of artistic works we glimpse apart from the gutters of noise.

Naturally, we don't all see exactly the same thing, but I think there's a tendency toward shared assumptions - that comic books are made for the market, live and die by their success thereupon, and may later be evaluated or reevaluated in the context of that audience's gift or lack of appreciation, as tossed against the appreciation of peers or the reaction of society, or 'the form,' or 'the industry.'

Rory Hayes created two well-known comic book series. One was Bogeyman Comics, which ran for three issues (1969-70), and contained horror comics by Hayes and guests. The other was Cunt Comics, a pornographic one-off from '69 that met with nearly unbridled loathing from unacclimated readers, raised bona-fied questions among some as to the author's mental health, and actually actually set the fucking printing press on fire as its final copies promenaded into being, devouring most of Hayes' original art for the project, as if the devil himself simply had to add those pieces to his personal collection, without delay.

This book, a $22.95 softcover from Fantagraphics -- edited by Dan Nadel & Glenn Bray -- reprints what appears to be the entirety of that most ill-fated comic, along with a large portion of the Bogeyman material and various odds 'n ends, across 144 b&w and color pages. Are they good comics? Well, I can tell you I sat down hoping to merely sample a few pages, and found myself devouring the entire book in one sitting, so I suppose they worked for me, yes.

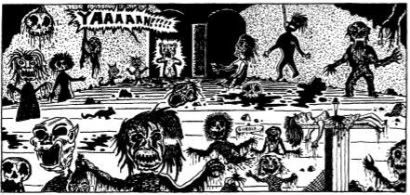

They're not 'easy' comics, in that Hayes has a way of setting up straightforward narratives -- slavishly informed by the pre-Code horror blueprint -- only to collapse them into primal sequences of stalking or terror, or crazed hallucination & revelation, like he can't wait to get to the good stuff.

The sex material rarely exceeds three or four pages in length, depicting ecstatically painful acts and mutations, severed cocks erupting from a woman's vagina to stangle her female partner, a black blob oozing out from between another woman's legs to devour a man's prick, pissing and shitting and bleeding and Charlie Brown jerking off. Hayes hadn't actually had any sex when he drew the stuff - it was all iconography, all application of the underground's most misogynistic means of assaulting politeness, all feeling, the sheer impetus of association and chemistry.

I can see Mark Beyer in Hayes' early art. I don't know what can be seen in Hayes' later, rounder, richer work. It may be folly to look for anyone but him.

Across the whole of this book, its Griffith two-pager and its Edwin "Savage Pencil" Pouncey life's summary and its [auto]biographical afterword by older brother Geoffrey Hayes, the illustrator of children's books, what emerges for me is a strong expression of the error in evaluating such comics as works in a history of capital and aesthetic influence. That is the book's character. Even its own errors -- particularly a nasty bit where a specific, much-heralded story is refered to by different titles and years of release between Pouncey's essay and the table of contents -- seem keyed toward sabotaging the impulse to catalog, the passion of collecting, the instant acknowledgement of such comics as items in competition for attention, inclusion of a handy Rory Hayes checklist notwithstanding.

What is made plain is that making comics -- even smut comics at the behest of fellows -- was always a personal satisfaction for Hayes, an artist who never used a proper pen until his publisher showed him how. I'm genuinely not sure if Hayes really cared if anyone bought his comics, although it's made clear he had a natural desire for affection, affirmation. He certainly didn't squirrel his art away -- these comics were published, after all -- but the notion remains that all of these stories would have played out in his head in much the same manner had they never gone down on paper.

The elder Hayes opines that the creation of Cunt served as a cathartic release of his demons, but simply looking at some of the younger Hayes' stories reveals an expression of a man's interior experience, as unfettered as it gets when processed through an artistic medium.

A bear lands on a weird planet, wandering through a rotten structure, encountering a dead creature that has scrawled "WE TRIED" on the floor, fleeing from a giant monster until Hayes' Bogeyman invites him into his maw for escape. A woman pumps unspecified drugs into her arm, after which a hand erupts from her skull and goblins climb out, growing to massive size, wrapping their legs around skyscrapers and screaming until everything is mad, then quiet. An ugly man has the urge to mutilate until he spies a denuded nipple, causing an eye to rip from its socket and careen through space, finally crashing into a planet of teddy bears and splitting the whole thing apart, leaving a single bear floating in the void and wondering "When in the fuck will we ever learn?"

The book's supplements bolster this curious presentation of public solitude, not necessarily defeating the possibility of comparative or historical-contextual criticism, but forcing greater attention to be paid to the work as an expression of a life's status. It is beheld, then held as beheld. It makes a wonderful companion volume to Lynda Barry's What It Is, the best comic of 2008 so far, and a mission statement for artistic creation as a purely personal act. Consider this newer book illustrative of such action, seen from several perspectives, from your own to Hayes' himself, via a 1973 interview. He has words about art-as-therapy, words about comics-as-commerce, even words about comics criticism:

"I think criticism tends to destroy more than it does to help. There's too much criticism. If people would just look at something and see it for itself. People have a really bad habit of comparing. I can look at really poorly drawn stuff and see something there."

What catches my eye is the "comparing." One better than the other. Give one a trophy, hail it. Hold it up to history, vaunt its vitality in the culture. Makes for criticism. Nothing wrong with that.

But Hayes had his mind out in space, I expect, even without the drugs. Look back to that quote in my title. Evolved into cinders from the cosmos.

He's right. Many of you I'm sure are aware that the elements that make up everything we see, and our eyes as well, originate from the heat of early stars, untold trillions of transformations, subtle and violent, resulting in the birth of that shit you took a while ago and the comic book website you're now reading. The height of your health was contained in space, your inevitable decline prenatal in outer bodies. The cinders that were Rory Hayes, three years from death, did evolve from that same place. He, immortal for now in Bill Griffith's comic, saw that.

Griffith's comic won't be around forever, obviously. Neither will this post, nor the book I'm reviewing. Nor me, nor you, nor any of the artistic works that we might appreciate in whatever manner, nor anything our species ever does in any way. In 150 or so years, every human being currently alive on this planet will be dead, and replaced by a somewhat greater number of entirely new human beings, although societies and philosophies and religions and such will endeavor to provide continuity, until they too pass, and the sun eventually eats the planet, and that, as they say, is that.

Such is this book's posture. It is not a rehabilitation of Rory Hayes' 'career' in 'comics,' because its primary mode of function is to disavow the necessity of reading his work as a part of the wider underground, and to advocate the idea of reading his work as him, as purely acts of life, as a temporary record of living in a certain time and place, as a fortunate reader's look into what a man thought, sketched out from the slowed scenery of his popular culture and his beloved teddies, his symbols and desires, so direct a comics translation as to force an evaluation of the originating tongue. It's creation we're all capable of, comics any one of us can make.

Until we're all dead. Like Rory Hayes is.

The quote above isn't anything Rory Hayes put in a comic. His writing doesn't quote well, prone to grammar errors and flat declaration as it is, a cadence burnt into the brain from old horrors, movies and comics, condensed and whittled into the stuff of ready recollection. There seems to be no filter.

No, all of those caps come from something Hayes said, as recorded in Bill Griffith's utterly beautiful tribute to Hayes, a two-page comic from 1980, depicting its still-young subject walking through a rainstorm on the third evening of his latest pharmaceutical binge, clutching his beloved, talking teddy bear character Pooh Rass in his arms and narrating his screenplay to the grand horror movie of his dreams, undeterred by the knife plunged into his chest and the blood soaking into his shirt. It would still be three years before Hayes died at 34, dead from drugs, still young.

Rory Hayes was an underground cartoonist in the late-'60s/early-'70s heyday of comix-with-an-x. You might call him an "artist's artist," in that his work was often unpopular with the underground readership, though Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, Griffith and others were among his admirers. And if you accept the dichotomy of the underground era as split between talents who loved EC's humor comics best -- the Crumbs and Spiegelmans and such -- and those who adored the horror and fantasy and mayhem -- Greg Irons, Richard Corben -- Hayes becomes oddly miraculous, in that his own tastes sat so clearly with the latter, yet his memory rests mainly in the renown of the former.

But memory, generic memory, critical memory, history, is so damn slippery, greasing our travel back in time until we move with such velocity that our surroundings seem no more than speed lines, our perceptions limited to what narratives we are already prone to recognizing from those sequential images of artistic works we glimpse apart from the gutters of noise.

Naturally, we don't all see exactly the same thing, but I think there's a tendency toward shared assumptions - that comic books are made for the market, live and die by their success thereupon, and may later be evaluated or reevaluated in the context of that audience's gift or lack of appreciation, as tossed against the appreciation of peers or the reaction of society, or 'the form,' or 'the industry.'

Rory Hayes created two well-known comic book series. One was Bogeyman Comics, which ran for three issues (1969-70), and contained horror comics by Hayes and guests. The other was Cunt Comics, a pornographic one-off from '69 that met with nearly unbridled loathing from unacclimated readers, raised bona-fied questions among some as to the author's mental health, and actually actually set the fucking printing press on fire as its final copies promenaded into being, devouring most of Hayes' original art for the project, as if the devil himself simply had to add those pieces to his personal collection, without delay.

This book, a $22.95 softcover from Fantagraphics -- edited by Dan Nadel & Glenn Bray -- reprints what appears to be the entirety of that most ill-fated comic, along with a large portion of the Bogeyman material and various odds 'n ends, across 144 b&w and color pages. Are they good comics? Well, I can tell you I sat down hoping to merely sample a few pages, and found myself devouring the entire book in one sitting, so I suppose they worked for me, yes.

They're not 'easy' comics, in that Hayes has a way of setting up straightforward narratives -- slavishly informed by the pre-Code horror blueprint -- only to collapse them into primal sequences of stalking or terror, or crazed hallucination & revelation, like he can't wait to get to the good stuff.

The sex material rarely exceeds three or four pages in length, depicting ecstatically painful acts and mutations, severed cocks erupting from a woman's vagina to stangle her female partner, a black blob oozing out from between another woman's legs to devour a man's prick, pissing and shitting and bleeding and Charlie Brown jerking off. Hayes hadn't actually had any sex when he drew the stuff - it was all iconography, all application of the underground's most misogynistic means of assaulting politeness, all feeling, the sheer impetus of association and chemistry.

I can see Mark Beyer in Hayes' early art. I don't know what can be seen in Hayes' later, rounder, richer work. It may be folly to look for anyone but him.

Across the whole of this book, its Griffith two-pager and its Edwin "Savage Pencil" Pouncey life's summary and its [auto]biographical afterword by older brother Geoffrey Hayes, the illustrator of children's books, what emerges for me is a strong expression of the error in evaluating such comics as works in a history of capital and aesthetic influence. That is the book's character. Even its own errors -- particularly a nasty bit where a specific, much-heralded story is refered to by different titles and years of release between Pouncey's essay and the table of contents -- seem keyed toward sabotaging the impulse to catalog, the passion of collecting, the instant acknowledgement of such comics as items in competition for attention, inclusion of a handy Rory Hayes checklist notwithstanding.

What is made plain is that making comics -- even smut comics at the behest of fellows -- was always a personal satisfaction for Hayes, an artist who never used a proper pen until his publisher showed him how. I'm genuinely not sure if Hayes really cared if anyone bought his comics, although it's made clear he had a natural desire for affection, affirmation. He certainly didn't squirrel his art away -- these comics were published, after all -- but the notion remains that all of these stories would have played out in his head in much the same manner had they never gone down on paper.

The elder Hayes opines that the creation of Cunt served as a cathartic release of his demons, but simply looking at some of the younger Hayes' stories reveals an expression of a man's interior experience, as unfettered as it gets when processed through an artistic medium.

A bear lands on a weird planet, wandering through a rotten structure, encountering a dead creature that has scrawled "WE TRIED" on the floor, fleeing from a giant monster until Hayes' Bogeyman invites him into his maw for escape. A woman pumps unspecified drugs into her arm, after which a hand erupts from her skull and goblins climb out, growing to massive size, wrapping their legs around skyscrapers and screaming until everything is mad, then quiet. An ugly man has the urge to mutilate until he spies a denuded nipple, causing an eye to rip from its socket and careen through space, finally crashing into a planet of teddy bears and splitting the whole thing apart, leaving a single bear floating in the void and wondering "When in the fuck will we ever learn?"

The book's supplements bolster this curious presentation of public solitude, not necessarily defeating the possibility of comparative or historical-contextual criticism, but forcing greater attention to be paid to the work as an expression of a life's status. It is beheld, then held as beheld. It makes a wonderful companion volume to Lynda Barry's What It Is, the best comic of 2008 so far, and a mission statement for artistic creation as a purely personal act. Consider this newer book illustrative of such action, seen from several perspectives, from your own to Hayes' himself, via a 1973 interview. He has words about art-as-therapy, words about comics-as-commerce, even words about comics criticism:

"I think criticism tends to destroy more than it does to help. There's too much criticism. If people would just look at something and see it for itself. People have a really bad habit of comparing. I can look at really poorly drawn stuff and see something there."

What catches my eye is the "comparing." One better than the other. Give one a trophy, hail it. Hold it up to history, vaunt its vitality in the culture. Makes for criticism. Nothing wrong with that.

But Hayes had his mind out in space, I expect, even without the drugs. Look back to that quote in my title. Evolved into cinders from the cosmos.

He's right. Many of you I'm sure are aware that the elements that make up everything we see, and our eyes as well, originate from the heat of early stars, untold trillions of transformations, subtle and violent, resulting in the birth of that shit you took a while ago and the comic book website you're now reading. The height of your health was contained in space, your inevitable decline prenatal in outer bodies. The cinders that were Rory Hayes, three years from death, did evolve from that same place. He, immortal for now in Bill Griffith's comic, saw that.

Griffith's comic won't be around forever, obviously. Neither will this post, nor the book I'm reviewing. Nor me, nor you, nor any of the artistic works that we might appreciate in whatever manner, nor anything our species ever does in any way. In 150 or so years, every human being currently alive on this planet will be dead, and replaced by a somewhat greater number of entirely new human beings, although societies and philosophies and religions and such will endeavor to provide continuity, until they too pass, and the sun eventually eats the planet, and that, as they say, is that.

Such is this book's posture. It is not a rehabilitation of Rory Hayes' 'career' in 'comics,' because its primary mode of function is to disavow the necessity of reading his work as a part of the wider underground, and to advocate the idea of reading his work as him, as purely acts of life, as a temporary record of living in a certain time and place, as a fortunate reader's look into what a man thought, sketched out from the slowed scenery of his popular culture and his beloved teddies, his symbols and desires, so direct a comics translation as to force an evaluation of the originating tongue. It's creation we're all capable of, comics any one of us can make.

Until we're all dead. Like Rory Hayes is.

<< Home