All That Sludge

*Yeah, told you my posting was gonna by shit. Sorry about that.

LAST WEEK'S REVIEWS:

Swallow Me Whole (this is a book to look out for, though; I think it's really bound to hit some people pretty hard, and it's got some strong style behind it)

More planned for this week, much more, with the time to get it done too.

*Dreadful Self-Promotion Dept: Here we go - the full schedule of events for this weekend's SPX 2008 is now up. I'm involved in two events happening on Saturday: at 1:30 PM I'm part of an hour-long Critic's Roundtable with Gary Groth, Tim Hodler and Rob Clough in the "Conference Room" (I think all this stuff is downstairs from the main show); and at 3:00 PM I'm moderating an hour-long Q&A gala with Bryan Lee O'Malley in the "Auditorium" (I think they have free water!). Plenty more going on that day and the next, including a Marc Singer panel on election cartoons on Sunday (2:30 PM, Conference Room).

Doors open for the show at 11:00 AM on Saturday and 12:00 PM on Sunday; admission is $8.00 for one day, $15.00 for both. Everyone will be there (Fanfare/Ponent Mon!) with many things.

*Also with the many things?

THIS WEEK IN COMICS!

Against Pain: Oh yes, a 128-page compilation of various and sundry anthology strips and short projects by the altogether excellent Ron Regé, Jr. I expect the star of the show for many (and probably the longest feature overall) will be 2000's Boys (written by Joan Reidy), a funny 24-page collection of awry romance/lust, originally published as a pamphlet by the lamented Highwater Books. But it's all probably going to read nice. From Drawn and Quarterly, $24.95.

My Brain is Hanging Upside Down: New from Pantheon, a 128-page, $24.95 color hardcover collection of various dreams, fragments and continuities by David Heatley, including strips from McSweeney's #13, Kramers Ergot 5 and his own two-issue pamphlet series Deadpan. New stuff too, but not the (incomplete) serial from MOME or any of his longform I'm Open project. Buckle up for portraiture by way of accumulated vignettes, the procedure made somewhat literal by piles of tiny story panels. Cute art mixed with explicit/gross sex too. Preview, production art and lots of background here; an added excerpt here. Er, don't follow those links while at the altar or anything.

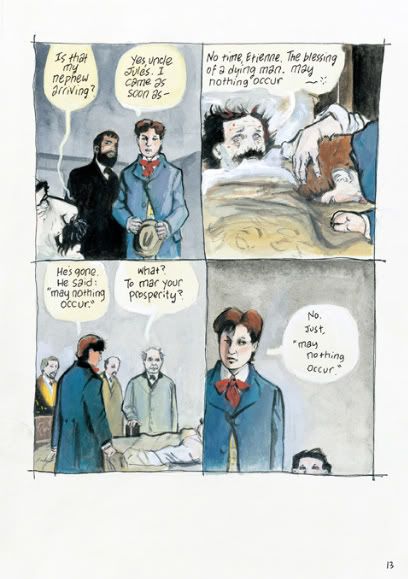

Aya of Yop City: Drawn and Quarterly (yes, it's one of those 'deluge' weeks for Diamond) had some nice success with last year's English translation of Aya, a 2005 French album from writer Marguerite Abouet and artist Clément Oubrerie, so here's the 2006 Vol. 2, under a self-sufficient title (the series is currently up to Vol. 3 in Europe). It's more soapy romance and familial/community bonds in the late '70s Ivory Coast of Abouet's childhood. Hardcover, 112 color pages, $19.95. Preview here, and also here.

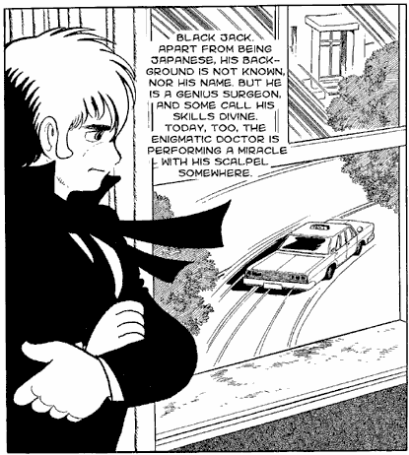

Top 10 Season Two #1 (of 4): Well I'll be goddamned - it's a new America's Best Comics miniseries. Almost in time for the 10th anniversary of Season One, actually. The writer is former co-artist Zander Cannon (with Big Time Attic cohort Kevin Cannon, no relation), and the visuals are from co-creator Gene Ha (from Z. Cannon's layouts). Have a look; I'd totally forgotten this was still in the pipeline.

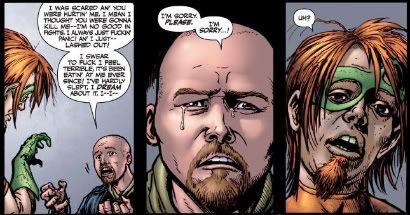

The Alcoholic: This is the comics debut of prose novelist Jonathan Ames, a 136-page, $19.99 Vertigo original hardcover about a broken-hearted, oft-trashed prose novelist named 'Jonathan A.' who encounters many events in a "hilarious, excruciating, bizarre and universal" story, or so I'm told. Art by Dean Haspiel; preview here.

C'est Bon Anthology Vol. 5: Being the latest in this Sweden-based ongoing presentation of international comics art. Lineup of contributors here. Found in Diamond's epic Merchandise section, along with your very own 30 Years of 2000 AD: Judge Dredd trading cards box. Oooh, I hope I pull the Grant Morrison run!!

Moomin: The Complete Tove Jansson Comic Strip Vol. 3 (of 5): Your annual dose of Moomins from Drawn and Quarterly, a 104-page, $19.95 hardcover collecting five more storylines from Jansson's popular newspaper strip of the '50s. I anticipate gentle satire and sweetly misplaced longing. Diamond is also offering (again) D&Q's second Chris Ware sketchbook release, The ACME Novelty Datebook: Vol. 2, 1995-2002, for those who missed it. I liked the page where he's reading an issue of Angry Youth Comix wherein Johnny Ryan is sassing him, so he banishes it to a garbage heap with copies of Lo-Jinx and Doofus visible on top. I mean, c'mon Chris Ware... Doofus and his light-hearted jests only sought to raise a smile, as would a tickly autumn breeze or a formidable inheritance. He is love.

The Night of Your Life: A 256-page, $15.95 Dark Horse collection of Jesse Reklaw's weekly Slow Wave alternative strip, based on the dreams of readers since 1995. Sample.

Harvey Comics Classics Library Vol. 4: Baby Huey: Holy fuck, that huge bird broke a bunch of shit. Only $19.95 for 480 pages of total sensation. From Dark Horse.

The Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy Vol. 5: Huh. Yeah... we're fucking drowning in reprint quality. How's about $29.99 for 352 pages, covering 1938-39? From IDW.

Vignettes: The Director's Cut: This is also a book of reprints (not a movie), matching up Image founder Jim Valentino's 1985-88 Renegade series Valentino with his 2007 Image-published sequel-in-spirit Drawing From Life in a 144-page Image softcover, with extras. It's $14.99.

Meat Cake #17: The pamphlet format may yet die, but Dame Darcy's one-artist showcase will continue among the undead - bank on it. From Fantagraphics, b&w, $3.95, 32 pages. Slideshow.

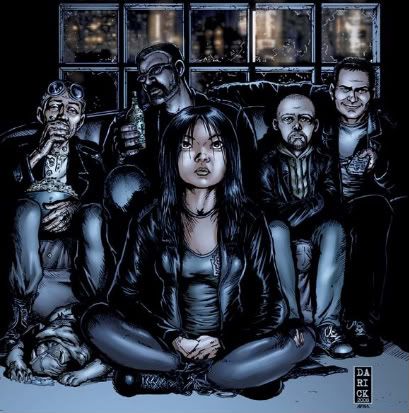

The Boys #23: Starting off the obligatory X-Men parody storyline; I imagine the basic idea of big money ultra-franchise superheroes could fit in pretty well with writer Garth Ennis' general industry-as-governance tone. Also on the money theme: variant covers, starting this issue! Preview here. For the hesitant among you, publisher Dynamite also has the series' third trade paperback this week, collecting issues #15-22 for $19.99.

No Hero #1 (of 7): The new Warren Ellis/Juan Jose Ryp superhero series from Avatar (which actually started with an issue #0 a while back, slowpoke); the topic is decades-spanning superhero franchise that sought to change society, and the drug casualties, violent team hopefuls and strange killings that surround it in 2011. Pencil preview here. Avatar also has Ellis' Doktor Sleepless #9 this week.

Punisher War Journal #24: Chaykin; Secret Invasion. Marvel also has a $15.99 softcover edition of The Punisher MAX: From First to Last this week, collecting all of the one or two-issue bits from Garth Ennis' run, with art by John Severin and Richard Corben, among others.

Sub-Mariner: The Depths #2 (of 5): Milligan, Ribic.

Army@Love: The Art of War #3 (of 6): Veitch.

Tor #6 (of 6): Kubert.

Batman #680: Oh god, it's the penultimate chapter of R.I.P. (Rest In Peace), and Garbage Bag Batman is totally going to use the magic of drugs to foil the Joker's foul scheme! Whatever it is! Fractured preview here!

Four Eyes #1: Another new Image series from the busy Man of Action studios, this time teaming writer Joe Kelly with artist Max Fiumara for the ongoing story of a young boy helping his family out of an American economic depression by wrangling dragons. Preview here; Fiumara's a talented artist that hasn't had the best of luck with front-of-Previews projects, but this stuff looks pretty strong.

The Soddyssey, And Other Tales of Supernatural Law: Ok. Deep breath. Once upon a time (so, 1979), a guy named Batton Lash created a comic strip about a pair of lawyers who represent monsters and fantasy horror figures. In 1994, the property spun out into a comic book titled Wolff & Byrd, Counselors of the Macabre, which changed its title to Supernatural Law in 1999. It's still ongoing, and up to issue #45. An initial run of collected editions started up in 1995, only to end in 1998 at Vol. 4. Then a new run of collections started up, compiling new issues while ducking back to present refurbished versions of old issues. That left some gaps as to what's actually in print; this book -- a 192-page b&w softcover, $17.95 -- will fill all of those gaps by picking back up issues #9-16 of the Wolff & Byrd series, retoned and relettered. With guest contributions by Steve Bissette, Jeff Smith, Bernie Wrightson, Charles Vess and others. Sample story here. Gah.

LAST WEEK'S REVIEWS:

Swallow Me Whole (this is a book to look out for, though; I think it's really bound to hit some people pretty hard, and it's got some strong style behind it)

More planned for this week, much more, with the time to get it done too.

*Dreadful Self-Promotion Dept: Here we go - the full schedule of events for this weekend's SPX 2008 is now up. I'm involved in two events happening on Saturday: at 1:30 PM I'm part of an hour-long Critic's Roundtable with Gary Groth, Tim Hodler and Rob Clough in the "Conference Room" (I think all this stuff is downstairs from the main show); and at 3:00 PM I'm moderating an hour-long Q&A gala with Bryan Lee O'Malley in the "Auditorium" (I think they have free water!). Plenty more going on that day and the next, including a Marc Singer panel on election cartoons on Sunday (2:30 PM, Conference Room).

Doors open for the show at 11:00 AM on Saturday and 12:00 PM on Sunday; admission is $8.00 for one day, $15.00 for both. Everyone will be there (Fanfare/Ponent Mon!) with many things.

*Also with the many things?

THIS WEEK IN COMICS!

Against Pain: Oh yes, a 128-page compilation of various and sundry anthology strips and short projects by the altogether excellent Ron Regé, Jr. I expect the star of the show for many (and probably the longest feature overall) will be 2000's Boys (written by Joan Reidy), a funny 24-page collection of awry romance/lust, originally published as a pamphlet by the lamented Highwater Books. But it's all probably going to read nice. From Drawn and Quarterly, $24.95.

My Brain is Hanging Upside Down: New from Pantheon, a 128-page, $24.95 color hardcover collection of various dreams, fragments and continuities by David Heatley, including strips from McSweeney's #13, Kramers Ergot 5 and his own two-issue pamphlet series Deadpan. New stuff too, but not the (incomplete) serial from MOME or any of his longform I'm Open project. Buckle up for portraiture by way of accumulated vignettes, the procedure made somewhat literal by piles of tiny story panels. Cute art mixed with explicit/gross sex too. Preview, production art and lots of background here; an added excerpt here. Er, don't follow those links while at the altar or anything.

Aya of Yop City: Drawn and Quarterly (yes, it's one of those 'deluge' weeks for Diamond) had some nice success with last year's English translation of Aya, a 2005 French album from writer Marguerite Abouet and artist Clément Oubrerie, so here's the 2006 Vol. 2, under a self-sufficient title (the series is currently up to Vol. 3 in Europe). It's more soapy romance and familial/community bonds in the late '70s Ivory Coast of Abouet's childhood. Hardcover, 112 color pages, $19.95. Preview here, and also here.

Top 10 Season Two #1 (of 4): Well I'll be goddamned - it's a new America's Best Comics miniseries. Almost in time for the 10th anniversary of Season One, actually. The writer is former co-artist Zander Cannon (with Big Time Attic cohort Kevin Cannon, no relation), and the visuals are from co-creator Gene Ha (from Z. Cannon's layouts). Have a look; I'd totally forgotten this was still in the pipeline.

The Alcoholic: This is the comics debut of prose novelist Jonathan Ames, a 136-page, $19.99 Vertigo original hardcover about a broken-hearted, oft-trashed prose novelist named 'Jonathan A.' who encounters many events in a "hilarious, excruciating, bizarre and universal" story, or so I'm told. Art by Dean Haspiel; preview here.

C'est Bon Anthology Vol. 5: Being the latest in this Sweden-based ongoing presentation of international comics art. Lineup of contributors here. Found in Diamond's epic Merchandise section, along with your very own 30 Years of 2000 AD: Judge Dredd trading cards box. Oooh, I hope I pull the Grant Morrison run!!

Moomin: The Complete Tove Jansson Comic Strip Vol. 3 (of 5): Your annual dose of Moomins from Drawn and Quarterly, a 104-page, $19.95 hardcover collecting five more storylines from Jansson's popular newspaper strip of the '50s. I anticipate gentle satire and sweetly misplaced longing. Diamond is also offering (again) D&Q's second Chris Ware sketchbook release, The ACME Novelty Datebook: Vol. 2, 1995-2002, for those who missed it. I liked the page where he's reading an issue of Angry Youth Comix wherein Johnny Ryan is sassing him, so he banishes it to a garbage heap with copies of Lo-Jinx and Doofus visible on top. I mean, c'mon Chris Ware... Doofus and his light-hearted jests only sought to raise a smile, as would a tickly autumn breeze or a formidable inheritance. He is love.

The Night of Your Life: A 256-page, $15.95 Dark Horse collection of Jesse Reklaw's weekly Slow Wave alternative strip, based on the dreams of readers since 1995. Sample.

Harvey Comics Classics Library Vol. 4: Baby Huey: Holy fuck, that huge bird broke a bunch of shit. Only $19.95 for 480 pages of total sensation. From Dark Horse.

The Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy Vol. 5: Huh. Yeah... we're fucking drowning in reprint quality. How's about $29.99 for 352 pages, covering 1938-39? From IDW.

Vignettes: The Director's Cut: This is also a book of reprints (not a movie), matching up Image founder Jim Valentino's 1985-88 Renegade series Valentino with his 2007 Image-published sequel-in-spirit Drawing From Life in a 144-page Image softcover, with extras. It's $14.99.

Meat Cake #17: The pamphlet format may yet die, but Dame Darcy's one-artist showcase will continue among the undead - bank on it. From Fantagraphics, b&w, $3.95, 32 pages. Slideshow.

The Boys #23: Starting off the obligatory X-Men parody storyline; I imagine the basic idea of big money ultra-franchise superheroes could fit in pretty well with writer Garth Ennis' general industry-as-governance tone. Also on the money theme: variant covers, starting this issue! Preview here. For the hesitant among you, publisher Dynamite also has the series' third trade paperback this week, collecting issues #15-22 for $19.99.

No Hero #1 (of 7): The new Warren Ellis/Juan Jose Ryp superhero series from Avatar (which actually started with an issue #0 a while back, slowpoke); the topic is decades-spanning superhero franchise that sought to change society, and the drug casualties, violent team hopefuls and strange killings that surround it in 2011. Pencil preview here. Avatar also has Ellis' Doktor Sleepless #9 this week.

Punisher War Journal #24: Chaykin; Secret Invasion. Marvel also has a $15.99 softcover edition of The Punisher MAX: From First to Last this week, collecting all of the one or two-issue bits from Garth Ennis' run, with art by John Severin and Richard Corben, among others.

Sub-Mariner: The Depths #2 (of 5): Milligan, Ribic.

Army@Love: The Art of War #3 (of 6): Veitch.

Tor #6 (of 6): Kubert.

Batman #680: Oh god, it's the penultimate chapter of R.I.P. (Rest In Peace), and Garbage Bag Batman is totally going to use the magic of drugs to foil the Joker's foul scheme! Whatever it is! Fractured preview here!

Four Eyes #1: Another new Image series from the busy Man of Action studios, this time teaming writer Joe Kelly with artist Max Fiumara for the ongoing story of a young boy helping his family out of an American economic depression by wrangling dragons. Preview here; Fiumara's a talented artist that hasn't had the best of luck with front-of-Previews projects, but this stuff looks pretty strong.

The Soddyssey, And Other Tales of Supernatural Law: Ok. Deep breath. Once upon a time (so, 1979), a guy named Batton Lash created a comic strip about a pair of lawyers who represent monsters and fantasy horror figures. In 1994, the property spun out into a comic book titled Wolff & Byrd, Counselors of the Macabre, which changed its title to Supernatural Law in 1999. It's still ongoing, and up to issue #45. An initial run of collected editions started up in 1995, only to end in 1998 at Vol. 4. Then a new run of collections started up, compiling new issues while ducking back to present refurbished versions of old issues. That left some gaps as to what's actually in print; this book -- a 192-page b&w softcover, $17.95 -- will fill all of those gaps by picking back up issues #9-16 of the Wolff & Byrd series, retoned and relettered. With guest contributions by Steve Bissette, Jeff Smith, Bernie Wrightson, Charles Vess and others. Sample story here. Gah.

Labels: this week in comics