Be sure and close the door. Eternity whips up a nasty draft sometimes.

The Amazing Remarkable Monsieur Leotard

This is a splendid, sad lark of a book, filled with odd amusements and formal horseplay, all keyed toward sifting through several fundamental ponderings of life and living; it's as playful as it is melancholic, a work that deems even the most storied life a ride of dips and jumps, its lowest lows and highest highs perhaps bringing us close to the very boders of the present - history and dreams and spirits lurking just above and below us, where we cannot routinely occupy the page.

All of this feeling is fundamental to the work's very construct, an impressively intuitive design cooked up by the ever-versatile Eddie Campbell, here working again with co-writer Dan Best (see also: 2005's Michael Chabon Presents: The Amazing Adventures of the Escapist #6, from Dark Horse). And while the surface qualities of the visuals are striking enough -- Campbell's painted scenes skillfully drift in and out of precision detail, all scooped into delightful wobbly panels -- a closer reading is necessary, I think, to fully appreciate the work's success.

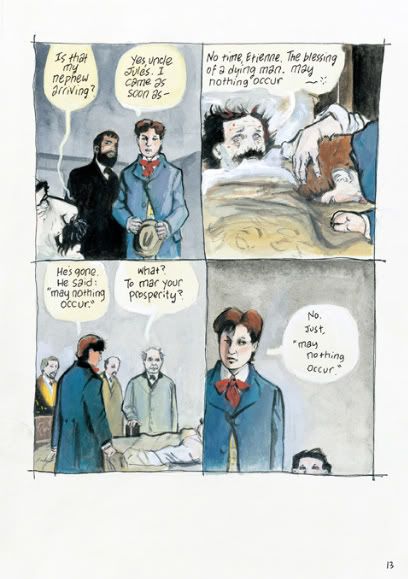

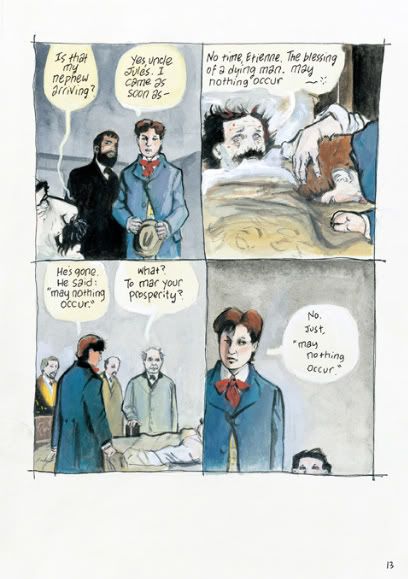

This is a work of historical fiction, involving the very real Jules Léotard, namesake of the tight-fitting garment and much-mustached legend of the 19th century trapeze. He died in 1870, at the age of 28; he doesn't make it very far into this book either, as all who've read the ad copy know. But Campbell lets him roar while he's up and about - his six pages of plotting primacy (the first images of the story) are nothing but single and double-page splashes, Leotard literally leaping through story and song in lieu of tiresome reality, until the sixth splash leaves him grounded in bed, wasting away from smallpox as the actual protagonist of the story enters from the bottom left.

That true main character is Leotard's nephew Etienne, his life picking up as Jules' winds down. Leotard remains wildly popular, you see, even as Paris shakes under the Franco-Prussion War and the circus animals are eaten as a matter of human survival. Etienne is left a fake mustache by his uncle, along with a final prayer: "May nothing occur." Our Hero then shamelessly ignores the latter bit of the legacy so as to put the former to quick use - after all, even if a new Monsieur Leotard isn't the thing to save the circus, it's surely at least something to be.

Oh, and Etienne is also left a blank book. This is crucially important, since he needs to fill up that book by filling up this book -- The Amazing Remarkable Monsieur Leotard, published by First Second, $16.95 for 128 color pages -- as the more immediately striking Uncle Jules and his splash pages didn't make it all that far. Campbell & Best thereby suggest that Etienne has come out from behind Jules' renown, and this book of this uncle's life (his uncle's blank book, remember) may become his own. Sure, he did it by straight-up appropriating his uncle's identity, but aren't we all prone to our little fictions of identity? And besides, it's not like he wasn't a Monsieur Leotard before.

And with Etienne's wakened life comes a new manner of our seeing it. Note all of the white space on the page above - that's how most of Etienne's are put together, with a 2 x 2 buckle of panels set in the center. Sometimes one or more panels reaches out into the void, or two in a row become combined into one. At one point they shake with terror and become detached, while another page finds a full-length image slicing away the second column. But mostly the 'story' exists in the center, brief and colorful.

Meanwhile, the void does not stay so blank. It quickly becomes evident that Campbell intends to use the space for any manner of optional information - things the characters can't directly see, being outside the boundaries of reality and all. It might be name labels for assorted characters, or pertinent quotes, or added historical information. Little scenes from history occasionally play out, like when Etienne's conversation with (actual) famed tight-rope walker Charles Blondin is literally surrounded by details from a wordless flashback, the sheer occasion unable to sit inside the 2 x 2 reality of thinking people. Elsewhere, a long boat trip has time's passage conveyed by the vessel's (mostly) smooth sailing atop the buckle, the ship's position shifting with each one-page vignette held in-panel. All that's out in the white is pertinent, but the stuff of extra-perception.

What mostly stands out, however, is the dead. Uncle Jules may not be dominating the page anymore, but he does pop in outside the panels for some comments or activity, as do devoured animals, departed performers, and the presence of foreshadowing. Even Campbell & Best wander in for a dream sequence, discussing the progression of their and Etienne's book up top ("But this is one of those characters that writes his own story") while both Leotards converse down bottom, the in-story living only able to access the realm while asleep. In the center, in a bed that could be divided into four squares if someone had a saw, Etienne tosses and turns, rolling around, and aging, page after page, until he sits up awake in his own full-page splash, wrinkled and gray, the sudden realization of it all dashing away some space from the blank eternal where people used to walk and talk.

It's sad, but it happens.

That is the stance of this book, and its beauty. What I just went through above isn't the only splash for Etienne. Oh no - every few pages sees some focusing event pound the fellow's in-panel life to vivid (joyful, tragic) fullness, whether it be a panorama of some exciting event, or a newspaper or transcribed account of some happening, or a look at an actual page of Etienne's book, laid out on top of one or two pages of ours. But always we return to the objective book, as objective as these things get.

The impact of this story cannot be divorced from its visuals; it all simply could not analogously exist outside of the comics form. Even beyond all I've mentioned, the rhythm of the pages grounds Campbell's & Best's plotting, which gallops through episodes from Etienne's advancing life in a manner that might seem vaporous otherwise. Or precious: characters often speak in an exclamatory manner, declaring intent and barking emotion with no fuss, like heroes in a youth adventure serial (and did I mention that among the circus' crew is an actual talking bear that walks on two legs and wears a top hat?). Indeed, reference is often made to 'the next episode,' even though the book wasn't serialized anywhere - what they're really talking about is the events that seem to define a life, the particulars that fill out memory's stuff and spark something in others, the fine work of a story.

Campbell & Best vary these particulars well, mixing swashbuckling challenges with the silent observation of some unique portion of a lover's body. There's a great, funny cameo by a character from a prior Campbell collaboration, but not ten pages away is a delicate, withering assessment of the racism and exploitation inherent to the circus life of the time, and an implied acknowledgement that while it's up to us to live our lives, so much of it is limited or exploded by circumstances of birth, tricks of time and place well beyond the painted color of our control.

Yet as the story bounces on springed shoes toward its conclusion, Campbell repeating his prior layouts and Etienne pooling his accumulated skills, both to good use, it becomes increasingly evident that no life in unlimited. That's hardly a profound revelation, particularly coming from an artist that's already shown us even immortality isn't forever, but it seems especially immediate coming from this work, in this manner, decades skipping by, life boxed away, so much beyond our reach.

The book is sad (as I put it) for that, but it is also true, and eloquent in its panels and grand gutters and pops of splashes and jests and visitations - strange fun emanating even from pages wet with sadness, suspense and exhilaration coursing through even the work's quietly masterful final pages, the chit-chat of friends and family drifting on and on and on.

Until, inevitably for books of limited pages and lives of finite hours, nothing more can occur.

This is a splendid, sad lark of a book, filled with odd amusements and formal horseplay, all keyed toward sifting through several fundamental ponderings of life and living; it's as playful as it is melancholic, a work that deems even the most storied life a ride of dips and jumps, its lowest lows and highest highs perhaps bringing us close to the very boders of the present - history and dreams and spirits lurking just above and below us, where we cannot routinely occupy the page.

All of this feeling is fundamental to the work's very construct, an impressively intuitive design cooked up by the ever-versatile Eddie Campbell, here working again with co-writer Dan Best (see also: 2005's Michael Chabon Presents: The Amazing Adventures of the Escapist #6, from Dark Horse). And while the surface qualities of the visuals are striking enough -- Campbell's painted scenes skillfully drift in and out of precision detail, all scooped into delightful wobbly panels -- a closer reading is necessary, I think, to fully appreciate the work's success.

This is a work of historical fiction, involving the very real Jules Léotard, namesake of the tight-fitting garment and much-mustached legend of the 19th century trapeze. He died in 1870, at the age of 28; he doesn't make it very far into this book either, as all who've read the ad copy know. But Campbell lets him roar while he's up and about - his six pages of plotting primacy (the first images of the story) are nothing but single and double-page splashes, Leotard literally leaping through story and song in lieu of tiresome reality, until the sixth splash leaves him grounded in bed, wasting away from smallpox as the actual protagonist of the story enters from the bottom left.

That true main character is Leotard's nephew Etienne, his life picking up as Jules' winds down. Leotard remains wildly popular, you see, even as Paris shakes under the Franco-Prussion War and the circus animals are eaten as a matter of human survival. Etienne is left a fake mustache by his uncle, along with a final prayer: "May nothing occur." Our Hero then shamelessly ignores the latter bit of the legacy so as to put the former to quick use - after all, even if a new Monsieur Leotard isn't the thing to save the circus, it's surely at least something to be.

Oh, and Etienne is also left a blank book. This is crucially important, since he needs to fill up that book by filling up this book -- The Amazing Remarkable Monsieur Leotard, published by First Second, $16.95 for 128 color pages -- as the more immediately striking Uncle Jules and his splash pages didn't make it all that far. Campbell & Best thereby suggest that Etienne has come out from behind Jules' renown, and this book of this uncle's life (his uncle's blank book, remember) may become his own. Sure, he did it by straight-up appropriating his uncle's identity, but aren't we all prone to our little fictions of identity? And besides, it's not like he wasn't a Monsieur Leotard before.

And with Etienne's wakened life comes a new manner of our seeing it. Note all of the white space on the page above - that's how most of Etienne's are put together, with a 2 x 2 buckle of panels set in the center. Sometimes one or more panels reaches out into the void, or two in a row become combined into one. At one point they shake with terror and become detached, while another page finds a full-length image slicing away the second column. But mostly the 'story' exists in the center, brief and colorful.

Meanwhile, the void does not stay so blank. It quickly becomes evident that Campbell intends to use the space for any manner of optional information - things the characters can't directly see, being outside the boundaries of reality and all. It might be name labels for assorted characters, or pertinent quotes, or added historical information. Little scenes from history occasionally play out, like when Etienne's conversation with (actual) famed tight-rope walker Charles Blondin is literally surrounded by details from a wordless flashback, the sheer occasion unable to sit inside the 2 x 2 reality of thinking people. Elsewhere, a long boat trip has time's passage conveyed by the vessel's (mostly) smooth sailing atop the buckle, the ship's position shifting with each one-page vignette held in-panel. All that's out in the white is pertinent, but the stuff of extra-perception.

What mostly stands out, however, is the dead. Uncle Jules may not be dominating the page anymore, but he does pop in outside the panels for some comments or activity, as do devoured animals, departed performers, and the presence of foreshadowing. Even Campbell & Best wander in for a dream sequence, discussing the progression of their and Etienne's book up top ("But this is one of those characters that writes his own story") while both Leotards converse down bottom, the in-story living only able to access the realm while asleep. In the center, in a bed that could be divided into four squares if someone had a saw, Etienne tosses and turns, rolling around, and aging, page after page, until he sits up awake in his own full-page splash, wrinkled and gray, the sudden realization of it all dashing away some space from the blank eternal where people used to walk and talk.

It's sad, but it happens.

That is the stance of this book, and its beauty. What I just went through above isn't the only splash for Etienne. Oh no - every few pages sees some focusing event pound the fellow's in-panel life to vivid (joyful, tragic) fullness, whether it be a panorama of some exciting event, or a newspaper or transcribed account of some happening, or a look at an actual page of Etienne's book, laid out on top of one or two pages of ours. But always we return to the objective book, as objective as these things get.

The impact of this story cannot be divorced from its visuals; it all simply could not analogously exist outside of the comics form. Even beyond all I've mentioned, the rhythm of the pages grounds Campbell's & Best's plotting, which gallops through episodes from Etienne's advancing life in a manner that might seem vaporous otherwise. Or precious: characters often speak in an exclamatory manner, declaring intent and barking emotion with no fuss, like heroes in a youth adventure serial (and did I mention that among the circus' crew is an actual talking bear that walks on two legs and wears a top hat?). Indeed, reference is often made to 'the next episode,' even though the book wasn't serialized anywhere - what they're really talking about is the events that seem to define a life, the particulars that fill out memory's stuff and spark something in others, the fine work of a story.

Campbell & Best vary these particulars well, mixing swashbuckling challenges with the silent observation of some unique portion of a lover's body. There's a great, funny cameo by a character from a prior Campbell collaboration, but not ten pages away is a delicate, withering assessment of the racism and exploitation inherent to the circus life of the time, and an implied acknowledgement that while it's up to us to live our lives, so much of it is limited or exploded by circumstances of birth, tricks of time and place well beyond the painted color of our control.

Yet as the story bounces on springed shoes toward its conclusion, Campbell repeating his prior layouts and Etienne pooling his accumulated skills, both to good use, it becomes increasingly evident that no life in unlimited. That's hardly a profound revelation, particularly coming from an artist that's already shown us even immortality isn't forever, but it seems especially immediate coming from this work, in this manner, decades skipping by, life boxed away, so much beyond our reach.

The book is sad (as I put it) for that, but it is also true, and eloquent in its panels and grand gutters and pops of splashes and jests and visitations - strange fun emanating even from pages wet with sadness, suspense and exhilaration coursing through even the work's quietly masterful final pages, the chit-chat of friends and family drifting on and on and on.

Until, inevitably for books of limited pages and lives of finite hours, nothing more can occur.

<< Home