Désastre Hurlant (T10): Psychomagic

"When you are linked to everyone, there are no enemies."

- Alejandro Jodorowsky, on the destination of the Fool's journey

***

The Metabarons

Let's face it: this is one everybody knows about. The one Warren Ellis and Matt Fraction praised to the sky. So nice, Humanoids printed it thrice. If you go up to someone who was around and sort of paying attention to the DC deal as it went down (and down, and down the drain) and you ask them about the projects that resulted, more often than not it'll be this one they cite. Humanoids pushed it good and hard, and for good reason - it's pretty easily the best of the Alejandro Jodorowsky series they managed to release.

As you probably know, The Metabarons is a spin-off of Jodorowsky's & Moebius' The Incal; the Metabaron himself was a leather-clad tough guy figure and all-star hired gun coerced into hunting down hapless protagonist John DiFool in exchange for the life of his beloved adopted child, Sunmoon. As was typical for the series, the Metabaron eventually inverted his attitude and promptly got lost in the din of supporting characters-as-tarot-symbols.

Everyone loves a tough guy, though, and Jodorowsky couldn't leave his burgeoning, new-ideas-on-every-page universe in stasis. First came the 1988 debut of Avant l'Incal, an official prequel series, drawn by Zoran Janjetov. Jodorowsky then opted to broaden his scope beyond the life and times of John DiFool with a new project tracking the secret history of the Metabaron's clan of killers; the first volume arrived in 1992, to be joined by a sibling series, The Technopriests, in 1998. The following year blessed us with Megalex, which I've read is also somehow tied in with things, although I couldn't tell you how off hand.

The Metabarons would continue until 2004, running for eight volumes in total; Humanoïdes' current all-in-one intégral edition box set weighs in at a formidable 528 pages. It was popular in Europe, and apparently deemed to have enough potential to hit in English-speaking environs that Humanoids elected to make it the center of its initial North American release effort, even though the series was still incomplete at that time.

As such, the Metabarons saw release in 2000 as Humanoids' very first pamphlet-format series, to be followed by "The Incal" (actually Avant l'Incal) in 2001 and the revived Métal Hurlant in 2002. All nudity was edited out, so as to cover the bases for Direct Market access. The release schedule was somewhat irregular, later contorting to accommodate the 2002 release of the French vol. 7, which brought the pamphlet series up to a total of 17 issues.

Four trade paperback collections of the (edited) pamphlet material were also released, bizarrely set up to factor in X number of pamphlets rather than individual storylines; as a result, Path of the Warrior (vol. 1) compiles the first two French volumes and 20 or so pages of the third, Blood and Steel (vol. 2) covers the remainder of the third French book with all of the fourth and part of the fifth, and Poet and Killer (vol. 3) tackles the rest of the fifth and all of the sixth. Only Immaculate Conception (vol. 4) conforms exactly to the original storylines, matching the French vol. 7 page-for-page, albeit in edited-for-content form. One might presume Humanoids was attempting to fit itself as firmly as possible into North American comic book culture, treating pamphlets as pamphlets, and X number to a trade, no matter how the storylines settled; it would be the oddest of all their compromises of the time.

The DC deal began several months after the concluding French vol. 8 was published. In spite of all packaging eccentricities, the prior run(s) of the material had picked up some favorable attention -- such as from the aforementioned Mssrs. Ellis & Fraction -- so a new run of DC/Humanoids softcovers was planned. This time the work was presented unedited, and neatly arranged at two French volumes per DC/Humanoids trade. And then the deal fell through before the concluding vol. 4 could show up, depriving English readers of the French vol. 8 (or a less-clothed vol. 7) to this very day.

But don't worry too much - the current DDP/Humanoids deal is slated to return to the material somehow, someday. That much seemed inevitable as soon as a new publishing arrangement was secured.

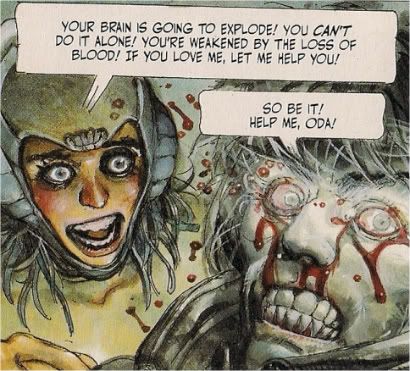

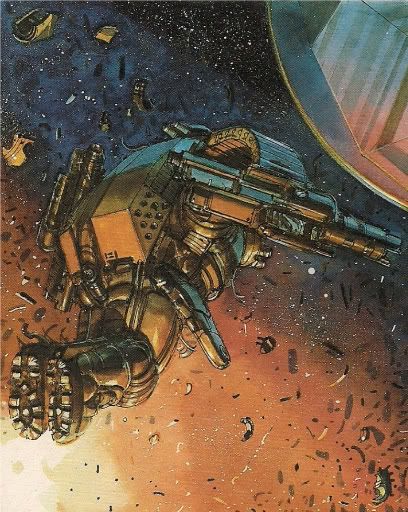

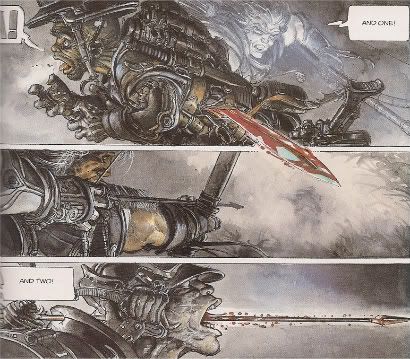

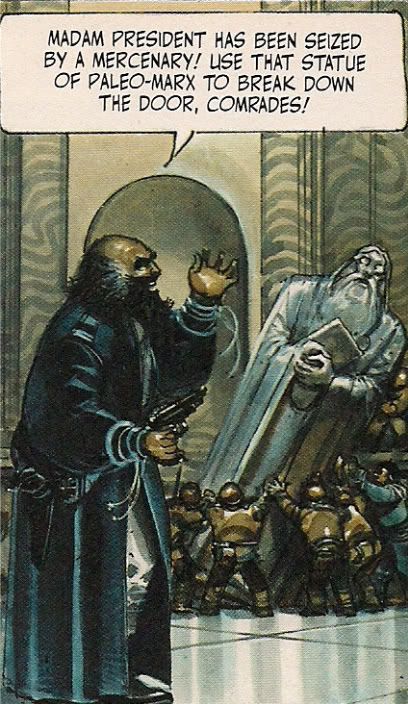

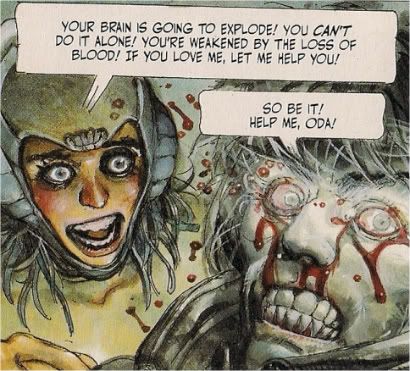

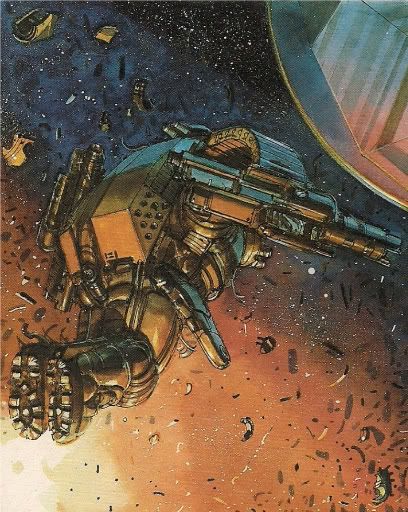

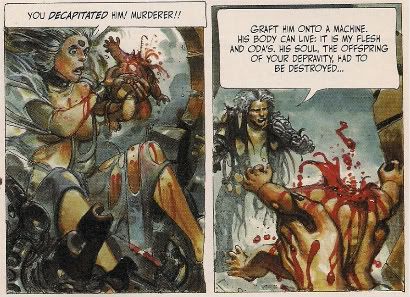

Why all the excitement, though? Well, surely one good reason is the presence of Argentine artist Juan Giménez, whose participation marked a crucial break from the Moebius-derived visuals of DiFool's journey. No longer were the lines clean and the colors flat; Giménez's universe is a dim, leather and chrome field of conflict, and while it'd be a mistake to label it 'realistic' -- there's actually a lot of rather vivid cartooning going on under the artist's painterly glaze -- every humanoid face seems nonetheless flush with anxiety and desire and hot fucking anger, in a way that makes the compositions of Moebius seem perpetually restrained.

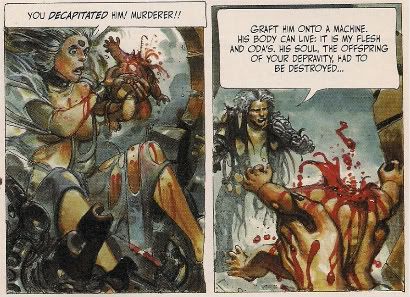

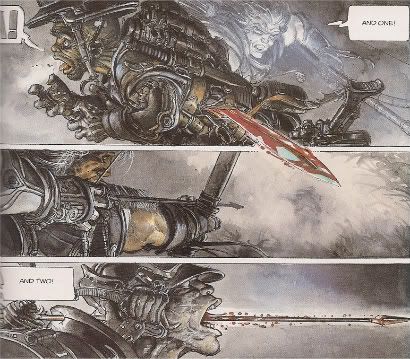

Plus: lots of big guns, sharp blades and gore-spattered action as you like it, True Believers. That's not to say Moebius couldn't put together some nice action pages, teeming with activity and woozy in scope, but Giménez has a visceral edge in addition to a firm grasp on spectacle; when his characters get hurt, fluid oozes everywhere and expressions twist and snarl impossibly.

His style may lack the pure design chops and mystic, dreamy quality of Moebius' best work, but it's admirably expressive for such a lacquered approach, and, to give the devil his due, probably more in line with what North American readers have come to expect from an expansive action comic. The tale is told in message board posts concerning the lameness of Moebius' work on the Halo Graphic Novel, or letters to those old The Airtight Garage-related pamphlets from Epic regarding the insufficiencies of the art in Silver Surfer: Parable, a debate immortalized by Quentin Tarantino's script additions to Crimson Tide.

Nobody writes scenes like that about Giménez's work - indeed, his characters' broad frames, flowing hair and obsessively detailed costumes suggest an alternate take on the Image Revolution just heating up in the U.S. in '92, and a more appealing one at that. Moreover, his approach is very much in tune with Jodorowsky's modifications to the epic tone of the Incal; subsequent offshoots would flaunt their own individual styles, from the digital sheen of the Technopriests to the edgeless 3D of Megalex, setting each area of the 'Jodoverse' apart as unique in focus, if united in broad concern.

And the Metabarons is certainly its parent's child. It's a sprawling, intergalactic opus -- the all-in-one French intégral box set weighs in at 528 pages -- compressed into small bursts of ideas and action that are hurled against the wall, one after another, over and over.

There's a magical subtext, touches of satire and a distinctly 'soft' approach to sci-fi devices; every starship in here is powered primarily by imagination, with a backup tank of allusion. The most alien entity around is subtlety - you'll know a tragedy has occurred when a father is out tracking thieves who've stolen his beloved, crippled son's horse (the only one in the entire universe, mind you), and he presumes the boy could never catch up with the villains so he throws his spear into the fog to lance the last one, but alas, he in fact murders his own son! And then the final, injured thief rises up behind him with his final breath and shoots his groin off with a laser cannon. For punctuation.

Yet it's is also a more refined work than the Incal, which often seemed unconcerned with any narrative development more complex than a steadily broadening scope. The Metabarons, in contrast, is keenly self-aware as to its status as a ballooning 'tale' of sorts - most of the story is narrated by Tonto, one of the robot servants of the 'present' Metabaron (i.e. the one from the Incal) to Lothar, a larger, more childlike robot, as they teem around the Metabunker hoping their adored master to acknowledge them, but mostly getting bored or sitting around, or contemplating suicide.

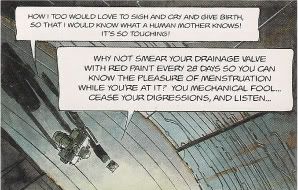

But while surely theater director Jodorowsky didn't happen upon this mild Waiting for Godot quality by accident, the effect is mostly utilitarian, patching up any gaps in the story's patchwork by zipping back to the robots every three to six pages or so, always to over-the-top praise for the story's thrill power:

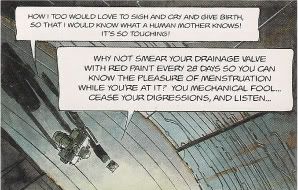

"Such a profoundly human tragedy! Just the thought of Honorata's body disintegrating into a torrent of flesh has fried four more of my diodes! Ooooooooo!"

"Ohmy-ohmy-ohmy! Tonto, how can he possibly defeat all those witches single-handed? Yipes! I wish I had one of those rubbery organs that humans call a bladder so I could piss myself in fear! Keep going, keep going!"

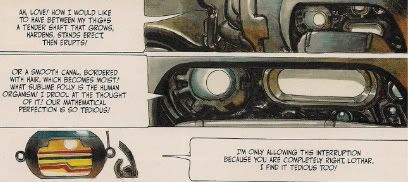

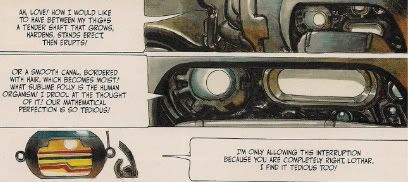

"My system started going haywire at the thought of a lusty bio-male slipping his reproductive shaft into Aghora's forbidden cavern!"

And so on, going farther and farther over the top until the French vol. 7 has Lothar literally ripping Tonto's limbs off to force his deliverance of each new development.

Yet there's also a secondary utility to the robots' presence; they're the chorus, the 'common' folk that deliver a Greek tragedy's exposition to the audience and behave in a manner that the heroes or gods cannot. In the 'present' of Jodorowsky's story -- initially positioned somewhere between the Incal and its prequel, but later amended in subsequent printings as the series went on -- there are no humans to be found in the Incal's city-shaft, so it's left to automatons to marvel at the dealings of people, some of them excellent killers like the Metabarons, and all of them beneficiaries of developing technologies that make men like something unto gods. The cosmos are flat.

The stories the robots tell make up the full history of the Metabarons, which is another refinement of the Incal's structure - the action can build and build and build, but here for the purposes of keeping up with technological advancements and the development of a clan's traits and traditions. It's useful to look at the series' French title, La Caste des Méta-Barons, because that's what the series truly is: the caste of the Metabarons, the succession that maintains the organization, parent to child.

Sometimes the series is also called the Saga of the Metabarons, which carries its own connotation - it's a saga in the classical sense, an epic telling of the feats of great 'heroes' and 'barons' (orally, from Tonto to Lothar), muscular and fair-haired like romantic Vikings or godly kings, although Jodorowsky is uninterested in keeping things set on any one culture's tradition.

Many have described the Metabarons as especially Greek and tragic in its telling, but while its writer does indeed take the opportunity to work through such beloved fan favorites as the Oedipus complex -- yep, one dude definitely has sex with his mom, if through biblical treachery, and a woman rips her eyes out in reaction to her father's lust for her -- there's also touches of Japanese samurai ethos, 20th century American pulp fiction (included an extended homage to Tarzan) and contemporary political struggles, reflecting Jodorowsky's attitude that diverse cultures' stories are united by common mythemes, which develop through interpretation into unique traditions.

This is the ambition of the Metabarons, the grandest of Jodorowsky's work in comics - to strike at variations on shared primal memes so as to express a new human story, one spanning six generations of vastly developed, yet sometimes devolved culture, all in popular space opera terms that might analogize to classical depictions of feats. All of the writer's themes are present -- it feels almost like a farewell work, it's so full of summary -- with spiritual evolution and familial strife chief among them. Indeed, here they are essentially the same thing.

In Louis Mouchet's 1994 French television documentary La constellation Jodorowsky (available online or as a supplement to the R1 dvd release of Fando y Lis), much time is devoted to the writer's activities as a lecturer and a personal-spiritual guide. Crucial to the portrayal is Jodorowsky's concept of 'psychomagic' (or 'psychogenealogy'), based on his notion that personal neurosis is inevitably, often subconsciously steeped in familial struggle, sometimes set back generations.

It's all perfectly related to Jodorowsky's comics concerns. All the myth and psychology, the Jung and opera, and all the damaging mothers from all of Jodorowsky's works -- Mouchet's film is where Jodorowsky notes his own strained relationship with his mother, whom he did not know for much of his adult life -- join with the Incal's idea of the tarot as a structure to form a theory of the family tree as its own temple, to be viewed and interpreted like cards, so as to isolate the root of your problems, and prescribe a specific act that might release the compression on your subconscious. Not unlike like a visit to your therapist, Dr. Jodorowsky, as a magical ritual.

Moebius is essentially Jodorowsky's co-star in the film, and he speaks of participating in just such a ritual, many of which appear to start by the patient instinctively selecting people from a crowd to role-play as his or her ancestors of varying degree. The patient arranges the selected players (the drawn cards, maybe) in a manner so as to spatially indicate proper familial dynamics. Jodorowsky talks the patient through, urging them to communicate with important ancestors, the applicable player answering automatically. Amazingly, Moebius tells of arranging his players into the body of a starship, in almost exact replication of a sequence he drew in the Incal as symbolic of the arrangement of Jodorowsky's characters-as-tarot-cards, without apparently knowing what was happening. They all blasted off, to somewhere.

Director Mouchet also winds up participating in the act at the film's conclusion, selecting Moebius to play his father, who was a poet. It's strange and compelling to watch, all of it taking place before a large crowd, Jodorowsky pacing and barking commands, like a director himself. I haven't liked all of Jodorowsky's comics (or movies, for that matter), but as I mentioned regarding the Incal, I never get the impression that he is even insincere, or that any of his works aren't some expression of a deeply held concern of his. Seeing his live reading of humans, his direction of actor-selected players, his construct of genealogy like his construct of the tarot like his metaphorical charge to his Moebius comic, I was struck by how fully his art seems to have become his life, how he is united in himself.

But Mouchet burns a volume of his father's poetry in the end. On camera. That was the magical act, the release from his adult troubles. There are limitations to art, it seems, and individual union can never only pertain to the individual. Mouchet knows, as does Jodorowsky.

The Metabarons is an extended psychomagic ritual, climactic to Jodorowsky's comics work. Where the Incal only shuffled and flipped characters-as-cards over its rising action, the very structure of the Metabarons presents an image of the Metabaron family tree - it's what the comic is, the story being told by Tonto to Lothar. We can observe the dignity of Baron Berard, patriarch of the Castaka clan, whose daughter married the space pirate Othon, who was saved from death by his own son in an act of compassion that sparked a battle that obliterated the family, birthing the Metabarons.

It is not a staid saga Jodorowsky is relating; it is criticism. The Metabarons are mighty heroes, but also killers, and always ruined in the end by the duties of 'honor' imposed on children by parents, and the children always grow to be as awful as their parents. That's the tragedy, and it seems to free Jodorowsky's powers of characterization - where so many of his personages are archetypical, the Metabarons cast is unique as shaded and complex, developing convincingly into terrible, sad people of great renown.

Honorata, a witch and spy who fell into pure love with Othon, and used magic to bear him a son, Aghnar, born in mid-air and thus weighed down with metal, and likewise weighed by the duties of battle and succession demanded by his cruel, mad father and his too-determined mother, who took the place of his dead bride and bore him a child, Steelhead, whose skull was blown off by his father's repulsion though technology can cure that, and so he destroyed his father by exploiting his ruined but real love for his mother-grandmother, and later fell in love with a space Marxist, Doña Vicenta, who drove him to graft the head of a poet onto him to become sensitive but she ripped her eyes out over her own father's lust for her, prompted unknowingly by Steelhead, and then only the metal part of him loved her and she bore him a son and a daughter and only one could be saved, so the son't brain went into the daughter, Aghora, who ruined Steelhead by ruining her mother, and was emotionally dead, and had a child with herself, because by then the technology had gotten to eliminate the need for mutuality in reproduction, a lonely science for lonely people, a lonely story for a lonely humanity, a lonely hero, and her son had no name, because his battles would be him, and he was the Metabaron.

And if we can see all of this, and we can isolate the most crucial pain points of this shared human myth, we can arrive at the biggest of Jodorowsky's big conclusions - the defeat of the human anxiety. A mirror of the conclusion to the Incal, but fleshy and tearful, tactile and willfully messy with emotion, a postscript duality for a work loaded with them already. Sharper. Deeper. Everyone. Everywhere. Everything. Everything. Everything.

True, the story rises and falls with Jodorowsky's momentary ideas - space vampires from beyond perception, parent-child squabbles as a proxy war between civilizations, etc. The DC/Humanoids run ended with the birth of Aghora, whose story (the French vol. 7) does start to show some wear on the concept; once you've got a hero(ine) who's almost totally emotionally desolate and capable of reproducing with herself, there's not a lot to work with beyond huge fights. Can the Metabaron defeat all opponents... while nine months pregnant?!

Fatigue seems to be setting in by then, although the stuff that came before is often wildly compelling, provided you're not allergic to unabashed planet-hopping space opera chock-full of traditional or semi-traditional gender roles; funny how the only female Metabaron is a total wreck due in part to being a guy stuck in a woman's body; very Freudian, even while Jodorowsky positions androgyny as a powerful goal for the union of the male and female aspect, a role filled in the Incal by Sunmoon, the adopted child of the present Metabaron. There's a nice bit toward the end of the Incal where the Metabaron is writhing around in a nightmare, struggling with the mutilation Aghora gave him, one of several accidents that we observe becoming traditions over the course of the Metabarons series - maybe time heals all wounds, as much as they hurt.

I haven't read the eighth and final French volume, although Wikipedia suggests it might pack a whopper of a plot twist, joining the Tonto and Lothar plot to the story they're telling/hearing and directly addressing the history of pain in the Metabarons line, as in 'among the story's characters.' That'd be nice; it'd be a shame if Jodorowsky didn't nail the landing. For now, it's a story without end for English readers.

Or even French readers, sort of. Since almost the beginning of the Humanoids deal, a Metabarons sidestory project had been hyped, something titled The Dreamshifters, to be written by Jodorowsky and illustrated by Travis Charest, the most stately son of the Image Revolution (see? told ya it was connected). Eventually the concept pivoted to become a series of self-contained albums focused on the origins of the current Metabarons's weapons; a small story was included in a 2002 odds 'n ends book titled The Metabarons: Alpha/Omega. A good while passed, until the first book finally hit France in 2008 under the title Les armes du Méta-Baron, with Charest joined on the art by Zoran Janjetov.

I'm under the impression the series is not to continue beyond that done-in-one book, which I'm certain the DDP/Humanoids partnership will be bringing to English eventually, along with the rest of the saga proper - fourth time's the charm. Jodorowsky is currently busy working on a new Metabarons prequel -- a prequel to a spin-off, sure -- Castika, with Das Pastoras of Wolverine: Switchback and the DC/Humanoids book Deicide. The first of three volumes was released in 2007. Expect that too, whenever it's done, if we're all still around.

He can probably go back forever. Like, back to the present, then forward from the past, a la Tezuka's Phoenix. No, physically he can't -- Jodorowsky's an 80-year old man, after all -- but mentally, I'm sure. That's the potential of a life's work, one premised on charting the pain of life. The art of Moebius was the Incal, the spirit, the broad, the tarot. The art of Giménez was the Metabarons, the body, the personal, the psychomagical. All corridors in the mansion of the self, one with eyes turned to the stars, one with eyes down on the body. I liked the second one more, although maybe it's just better from plain developed chops.

Jodorowsky's only human, you know.

- Alejandro Jodorowsky, on the destination of the Fool's journey

***

The Metabarons

Let's face it: this is one everybody knows about. The one Warren Ellis and Matt Fraction praised to the sky. So nice, Humanoids printed it thrice. If you go up to someone who was around and sort of paying attention to the DC deal as it went down (and down, and down the drain) and you ask them about the projects that resulted, more often than not it'll be this one they cite. Humanoids pushed it good and hard, and for good reason - it's pretty easily the best of the Alejandro Jodorowsky series they managed to release.

As you probably know, The Metabarons is a spin-off of Jodorowsky's & Moebius' The Incal; the Metabaron himself was a leather-clad tough guy figure and all-star hired gun coerced into hunting down hapless protagonist John DiFool in exchange for the life of his beloved adopted child, Sunmoon. As was typical for the series, the Metabaron eventually inverted his attitude and promptly got lost in the din of supporting characters-as-tarot-symbols.

Everyone loves a tough guy, though, and Jodorowsky couldn't leave his burgeoning, new-ideas-on-every-page universe in stasis. First came the 1988 debut of Avant l'Incal, an official prequel series, drawn by Zoran Janjetov. Jodorowsky then opted to broaden his scope beyond the life and times of John DiFool with a new project tracking the secret history of the Metabaron's clan of killers; the first volume arrived in 1992, to be joined by a sibling series, The Technopriests, in 1998. The following year blessed us with Megalex, which I've read is also somehow tied in with things, although I couldn't tell you how off hand.

The Metabarons would continue until 2004, running for eight volumes in total; Humanoïdes' current all-in-one intégral edition box set weighs in at a formidable 528 pages. It was popular in Europe, and apparently deemed to have enough potential to hit in English-speaking environs that Humanoids elected to make it the center of its initial North American release effort, even though the series was still incomplete at that time.

As such, the Metabarons saw release in 2000 as Humanoids' very first pamphlet-format series, to be followed by "The Incal" (actually Avant l'Incal) in 2001 and the revived Métal Hurlant in 2002. All nudity was edited out, so as to cover the bases for Direct Market access. The release schedule was somewhat irregular, later contorting to accommodate the 2002 release of the French vol. 7, which brought the pamphlet series up to a total of 17 issues.

Four trade paperback collections of the (edited) pamphlet material were also released, bizarrely set up to factor in X number of pamphlets rather than individual storylines; as a result, Path of the Warrior (vol. 1) compiles the first two French volumes and 20 or so pages of the third, Blood and Steel (vol. 2) covers the remainder of the third French book with all of the fourth and part of the fifth, and Poet and Killer (vol. 3) tackles the rest of the fifth and all of the sixth. Only Immaculate Conception (vol. 4) conforms exactly to the original storylines, matching the French vol. 7 page-for-page, albeit in edited-for-content form. One might presume Humanoids was attempting to fit itself as firmly as possible into North American comic book culture, treating pamphlets as pamphlets, and X number to a trade, no matter how the storylines settled; it would be the oddest of all their compromises of the time.

The DC deal began several months after the concluding French vol. 8 was published. In spite of all packaging eccentricities, the prior run(s) of the material had picked up some favorable attention -- such as from the aforementioned Mssrs. Ellis & Fraction -- so a new run of DC/Humanoids softcovers was planned. This time the work was presented unedited, and neatly arranged at two French volumes per DC/Humanoids trade. And then the deal fell through before the concluding vol. 4 could show up, depriving English readers of the French vol. 8 (or a less-clothed vol. 7) to this very day.

But don't worry too much - the current DDP/Humanoids deal is slated to return to the material somehow, someday. That much seemed inevitable as soon as a new publishing arrangement was secured.

Why all the excitement, though? Well, surely one good reason is the presence of Argentine artist Juan Giménez, whose participation marked a crucial break from the Moebius-derived visuals of DiFool's journey. No longer were the lines clean and the colors flat; Giménez's universe is a dim, leather and chrome field of conflict, and while it'd be a mistake to label it 'realistic' -- there's actually a lot of rather vivid cartooning going on under the artist's painterly glaze -- every humanoid face seems nonetheless flush with anxiety and desire and hot fucking anger, in a way that makes the compositions of Moebius seem perpetually restrained.

Plus: lots of big guns, sharp blades and gore-spattered action as you like it, True Believers. That's not to say Moebius couldn't put together some nice action pages, teeming with activity and woozy in scope, but Giménez has a visceral edge in addition to a firm grasp on spectacle; when his characters get hurt, fluid oozes everywhere and expressions twist and snarl impossibly.

His style may lack the pure design chops and mystic, dreamy quality of Moebius' best work, but it's admirably expressive for such a lacquered approach, and, to give the devil his due, probably more in line with what North American readers have come to expect from an expansive action comic. The tale is told in message board posts concerning the lameness of Moebius' work on the Halo Graphic Novel, or letters to those old The Airtight Garage-related pamphlets from Epic regarding the insufficiencies of the art in Silver Surfer: Parable, a debate immortalized by Quentin Tarantino's script additions to Crimson Tide.

Nobody writes scenes like that about Giménez's work - indeed, his characters' broad frames, flowing hair and obsessively detailed costumes suggest an alternate take on the Image Revolution just heating up in the U.S. in '92, and a more appealing one at that. Moreover, his approach is very much in tune with Jodorowsky's modifications to the epic tone of the Incal; subsequent offshoots would flaunt their own individual styles, from the digital sheen of the Technopriests to the edgeless 3D of Megalex, setting each area of the 'Jodoverse' apart as unique in focus, if united in broad concern.

And the Metabarons is certainly its parent's child. It's a sprawling, intergalactic opus -- the all-in-one French intégral box set weighs in at 528 pages -- compressed into small bursts of ideas and action that are hurled against the wall, one after another, over and over.

There's a magical subtext, touches of satire and a distinctly 'soft' approach to sci-fi devices; every starship in here is powered primarily by imagination, with a backup tank of allusion. The most alien entity around is subtlety - you'll know a tragedy has occurred when a father is out tracking thieves who've stolen his beloved, crippled son's horse (the only one in the entire universe, mind you), and he presumes the boy could never catch up with the villains so he throws his spear into the fog to lance the last one, but alas, he in fact murders his own son! And then the final, injured thief rises up behind him with his final breath and shoots his groin off with a laser cannon. For punctuation.

Yet it's is also a more refined work than the Incal, which often seemed unconcerned with any narrative development more complex than a steadily broadening scope. The Metabarons, in contrast, is keenly self-aware as to its status as a ballooning 'tale' of sorts - most of the story is narrated by Tonto, one of the robot servants of the 'present' Metabaron (i.e. the one from the Incal) to Lothar, a larger, more childlike robot, as they teem around the Metabunker hoping their adored master to acknowledge them, but mostly getting bored or sitting around, or contemplating suicide.

But while surely theater director Jodorowsky didn't happen upon this mild Waiting for Godot quality by accident, the effect is mostly utilitarian, patching up any gaps in the story's patchwork by zipping back to the robots every three to six pages or so, always to over-the-top praise for the story's thrill power:

"Such a profoundly human tragedy! Just the thought of Honorata's body disintegrating into a torrent of flesh has fried four more of my diodes! Ooooooooo!"

"Ohmy-ohmy-ohmy! Tonto, how can he possibly defeat all those witches single-handed? Yipes! I wish I had one of those rubbery organs that humans call a bladder so I could piss myself in fear! Keep going, keep going!"

"My system started going haywire at the thought of a lusty bio-male slipping his reproductive shaft into Aghora's forbidden cavern!"

And so on, going farther and farther over the top until the French vol. 7 has Lothar literally ripping Tonto's limbs off to force his deliverance of each new development.

Yet there's also a secondary utility to the robots' presence; they're the chorus, the 'common' folk that deliver a Greek tragedy's exposition to the audience and behave in a manner that the heroes or gods cannot. In the 'present' of Jodorowsky's story -- initially positioned somewhere between the Incal and its prequel, but later amended in subsequent printings as the series went on -- there are no humans to be found in the Incal's city-shaft, so it's left to automatons to marvel at the dealings of people, some of them excellent killers like the Metabarons, and all of them beneficiaries of developing technologies that make men like something unto gods. The cosmos are flat.

The stories the robots tell make up the full history of the Metabarons, which is another refinement of the Incal's structure - the action can build and build and build, but here for the purposes of keeping up with technological advancements and the development of a clan's traits and traditions. It's useful to look at the series' French title, La Caste des Méta-Barons, because that's what the series truly is: the caste of the Metabarons, the succession that maintains the organization, parent to child.

Sometimes the series is also called the Saga of the Metabarons, which carries its own connotation - it's a saga in the classical sense, an epic telling of the feats of great 'heroes' and 'barons' (orally, from Tonto to Lothar), muscular and fair-haired like romantic Vikings or godly kings, although Jodorowsky is uninterested in keeping things set on any one culture's tradition.

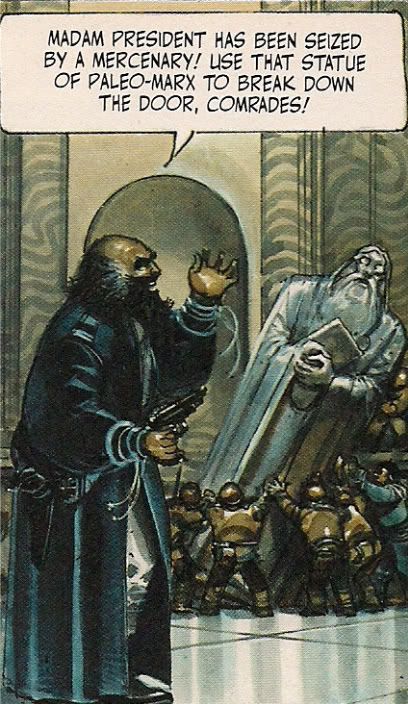

Many have described the Metabarons as especially Greek and tragic in its telling, but while its writer does indeed take the opportunity to work through such beloved fan favorites as the Oedipus complex -- yep, one dude definitely has sex with his mom, if through biblical treachery, and a woman rips her eyes out in reaction to her father's lust for her -- there's also touches of Japanese samurai ethos, 20th century American pulp fiction (included an extended homage to Tarzan) and contemporary political struggles, reflecting Jodorowsky's attitude that diverse cultures' stories are united by common mythemes, which develop through interpretation into unique traditions.

This is the ambition of the Metabarons, the grandest of Jodorowsky's work in comics - to strike at variations on shared primal memes so as to express a new human story, one spanning six generations of vastly developed, yet sometimes devolved culture, all in popular space opera terms that might analogize to classical depictions of feats. All of the writer's themes are present -- it feels almost like a farewell work, it's so full of summary -- with spiritual evolution and familial strife chief among them. Indeed, here they are essentially the same thing.

In Louis Mouchet's 1994 French television documentary La constellation Jodorowsky (available online or as a supplement to the R1 dvd release of Fando y Lis), much time is devoted to the writer's activities as a lecturer and a personal-spiritual guide. Crucial to the portrayal is Jodorowsky's concept of 'psychomagic' (or 'psychogenealogy'), based on his notion that personal neurosis is inevitably, often subconsciously steeped in familial struggle, sometimes set back generations.

It's all perfectly related to Jodorowsky's comics concerns. All the myth and psychology, the Jung and opera, and all the damaging mothers from all of Jodorowsky's works -- Mouchet's film is where Jodorowsky notes his own strained relationship with his mother, whom he did not know for much of his adult life -- join with the Incal's idea of the tarot as a structure to form a theory of the family tree as its own temple, to be viewed and interpreted like cards, so as to isolate the root of your problems, and prescribe a specific act that might release the compression on your subconscious. Not unlike like a visit to your therapist, Dr. Jodorowsky, as a magical ritual.

Moebius is essentially Jodorowsky's co-star in the film, and he speaks of participating in just such a ritual, many of which appear to start by the patient instinctively selecting people from a crowd to role-play as his or her ancestors of varying degree. The patient arranges the selected players (the drawn cards, maybe) in a manner so as to spatially indicate proper familial dynamics. Jodorowsky talks the patient through, urging them to communicate with important ancestors, the applicable player answering automatically. Amazingly, Moebius tells of arranging his players into the body of a starship, in almost exact replication of a sequence he drew in the Incal as symbolic of the arrangement of Jodorowsky's characters-as-tarot-cards, without apparently knowing what was happening. They all blasted off, to somewhere.

Director Mouchet also winds up participating in the act at the film's conclusion, selecting Moebius to play his father, who was a poet. It's strange and compelling to watch, all of it taking place before a large crowd, Jodorowsky pacing and barking commands, like a director himself. I haven't liked all of Jodorowsky's comics (or movies, for that matter), but as I mentioned regarding the Incal, I never get the impression that he is even insincere, or that any of his works aren't some expression of a deeply held concern of his. Seeing his live reading of humans, his direction of actor-selected players, his construct of genealogy like his construct of the tarot like his metaphorical charge to his Moebius comic, I was struck by how fully his art seems to have become his life, how he is united in himself.

But Mouchet burns a volume of his father's poetry in the end. On camera. That was the magical act, the release from his adult troubles. There are limitations to art, it seems, and individual union can never only pertain to the individual. Mouchet knows, as does Jodorowsky.

The Metabarons is an extended psychomagic ritual, climactic to Jodorowsky's comics work. Where the Incal only shuffled and flipped characters-as-cards over its rising action, the very structure of the Metabarons presents an image of the Metabaron family tree - it's what the comic is, the story being told by Tonto to Lothar. We can observe the dignity of Baron Berard, patriarch of the Castaka clan, whose daughter married the space pirate Othon, who was saved from death by his own son in an act of compassion that sparked a battle that obliterated the family, birthing the Metabarons.

It is not a staid saga Jodorowsky is relating; it is criticism. The Metabarons are mighty heroes, but also killers, and always ruined in the end by the duties of 'honor' imposed on children by parents, and the children always grow to be as awful as their parents. That's the tragedy, and it seems to free Jodorowsky's powers of characterization - where so many of his personages are archetypical, the Metabarons cast is unique as shaded and complex, developing convincingly into terrible, sad people of great renown.

Honorata, a witch and spy who fell into pure love with Othon, and used magic to bear him a son, Aghnar, born in mid-air and thus weighed down with metal, and likewise weighed by the duties of battle and succession demanded by his cruel, mad father and his too-determined mother, who took the place of his dead bride and bore him a child, Steelhead, whose skull was blown off by his father's repulsion though technology can cure that, and so he destroyed his father by exploiting his ruined but real love for his mother-grandmother, and later fell in love with a space Marxist, Doña Vicenta, who drove him to graft the head of a poet onto him to become sensitive but she ripped her eyes out over her own father's lust for her, prompted unknowingly by Steelhead, and then only the metal part of him loved her and she bore him a son and a daughter and only one could be saved, so the son't brain went into the daughter, Aghora, who ruined Steelhead by ruining her mother, and was emotionally dead, and had a child with herself, because by then the technology had gotten to eliminate the need for mutuality in reproduction, a lonely science for lonely people, a lonely story for a lonely humanity, a lonely hero, and her son had no name, because his battles would be him, and he was the Metabaron.

And if we can see all of this, and we can isolate the most crucial pain points of this shared human myth, we can arrive at the biggest of Jodorowsky's big conclusions - the defeat of the human anxiety. A mirror of the conclusion to the Incal, but fleshy and tearful, tactile and willfully messy with emotion, a postscript duality for a work loaded with them already. Sharper. Deeper. Everyone. Everywhere. Everything. Everything. Everything.

True, the story rises and falls with Jodorowsky's momentary ideas - space vampires from beyond perception, parent-child squabbles as a proxy war between civilizations, etc. The DC/Humanoids run ended with the birth of Aghora, whose story (the French vol. 7) does start to show some wear on the concept; once you've got a hero(ine) who's almost totally emotionally desolate and capable of reproducing with herself, there's not a lot to work with beyond huge fights. Can the Metabaron defeat all opponents... while nine months pregnant?!

Fatigue seems to be setting in by then, although the stuff that came before is often wildly compelling, provided you're not allergic to unabashed planet-hopping space opera chock-full of traditional or semi-traditional gender roles; funny how the only female Metabaron is a total wreck due in part to being a guy stuck in a woman's body; very Freudian, even while Jodorowsky positions androgyny as a powerful goal for the union of the male and female aspect, a role filled in the Incal by Sunmoon, the adopted child of the present Metabaron. There's a nice bit toward the end of the Incal where the Metabaron is writhing around in a nightmare, struggling with the mutilation Aghora gave him, one of several accidents that we observe becoming traditions over the course of the Metabarons series - maybe time heals all wounds, as much as they hurt.

I haven't read the eighth and final French volume, although Wikipedia suggests it might pack a whopper of a plot twist, joining the Tonto and Lothar plot to the story they're telling/hearing and directly addressing the history of pain in the Metabarons line, as in 'among the story's characters.' That'd be nice; it'd be a shame if Jodorowsky didn't nail the landing. For now, it's a story without end for English readers.

Or even French readers, sort of. Since almost the beginning of the Humanoids deal, a Metabarons sidestory project had been hyped, something titled The Dreamshifters, to be written by Jodorowsky and illustrated by Travis Charest, the most stately son of the Image Revolution (see? told ya it was connected). Eventually the concept pivoted to become a series of self-contained albums focused on the origins of the current Metabarons's weapons; a small story was included in a 2002 odds 'n ends book titled The Metabarons: Alpha/Omega. A good while passed, until the first book finally hit France in 2008 under the title Les armes du Méta-Baron, with Charest joined on the art by Zoran Janjetov.

I'm under the impression the series is not to continue beyond that done-in-one book, which I'm certain the DDP/Humanoids partnership will be bringing to English eventually, along with the rest of the saga proper - fourth time's the charm. Jodorowsky is currently busy working on a new Metabarons prequel -- a prequel to a spin-off, sure -- Castika, with Das Pastoras of Wolverine: Switchback and the DC/Humanoids book Deicide. The first of three volumes was released in 2007. Expect that too, whenever it's done, if we're all still around.

He can probably go back forever. Like, back to the present, then forward from the past, a la Tezuka's Phoenix. No, physically he can't -- Jodorowsky's an 80-year old man, after all -- but mentally, I'm sure. That's the potential of a life's work, one premised on charting the pain of life. The art of Moebius was the Incal, the spirit, the broad, the tarot. The art of Giménez was the Metabarons, the body, the personal, the psychomagical. All corridors in the mansion of the self, one with eyes turned to the stars, one with eyes down on the body. I liked the second one more, although maybe it's just better from plain developed chops.

Jodorowsky's only human, you know.

Labels: Hurlant

<< Home