The Crisis Embrace

I don't like 3-D comics much; never have. The last time I found a 3-D segment in a comic to be really effective was in Seven Soldiers #1 -- drawn by J.H. Williams III, also variant cover artist for this book -- where it was tucked away as an Easter Egg. It was the bit where Zatanna casts a spell to resolve the plot - I tried looking at it with the red and green glasses included with this new comic, but it didn't look so good.

That's another thing I don't like: building the 3-D glasses that come with these things. It's mostly my own problem - I'm of remarkably limited manual dexterity, utterly incapable of building anything useful with my hands. I'd sure be hopeless getting things to work in a post-cataclysm wasteland (but then, I guess that's what the cache of automatic firearms is for). I suspect the problem dates back to my childhood, when I got my copy of Shadowhawk II #3, the one where you're supposed to punch out a little of the cover so you can fold it upward, creating the illusion that Shadowhawk is bending his arms in a horrible, inhuman manner to reveal his exciting secret identity just for you. I ripped that fucking cover right off. Just clean off, like I was sending that shit to be pulped. It broke me, like Bane.

Maybe that's why another J.H. Williams III comic, Promethea #32, got to me so much. That was the last issue of the series, the one where him and Alan Moore and Todd Klein and José Villarrubia create this looping comics essay about magic and storytelling, and there's two ways to read it - you can go through it as a normal comic (which involved turning the book upside-down and reading backwards like manga and all sorts of thing), then you can pull all the pages apart and paste them together into a double-sided poster that displays the text in a different way while creating a giant image. The idea was wonderful - a final issue of a comic book series that urged you to physically destroy it in order to facilitate its recreation. Hell, I can do that!

This issue demands a smaller, more typical demolition. Just punching out '4-D Overvoid Viewers,' "forged from Superman's own cosmic armor." I'm glad I didn't screw it up; Superman's cosmic armor is kinda flimsy. It's also worth nothing that I usually read a bunch of my Wednesday comics in the Wegmans parking lot -- Wegmans being a local(ish) super-grocer chain that keeps 15 types of coffee going at once and sells those melon sodas with the marble in the bottle -- so I'd probably look pretty silly holding up broken 3-D glasses to my eyes in public. Not so with whole, unmolested 3-D glasses, though, the cardboard craft labor of my own fingers - had anyone asked me then what the hell I was doing, I'd reply: "The future."

Happy as I was, I found that Final Crisis: Superman Beyond #1 (no '3D' in the official title) was about the same as your typical contemporary Ray Zone-powered 3-D comic. I do think the whole concept works well for a Grant Morrison-written story like this, mind you. The last time Ray Zone did funnybook 3-D was in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier - god, Alan Moore again! The pertinent segment in there saw most of the characters enter the Blazing World of collected fictions to plan their next move; not a bad place for the pages plane to drop back, although it all seemed awfully studied, in that Alan Moore way.

After all, Promethea promulgated that old idea of spacetime as a 4D system of eternal moments that our perceptions move through; so really, out there somewhere, I am reading Deathmate: Red unto perpetuity (um, as much as perpetuity exists in... that... ah, just forget it). It always seemed to me that the comics form acted as an imperfect model of spacetime, in that way, with our godly readers' eyes peeping into certain temporal zones, panels, free to move backward and forward - that final issue made the reader move in every which way, to best appreciate that nature, I thought.

Moore's whole concept of End of the World -- the lynchpin of his America's Best Comics megastory, which Promethea concluded -- relied upon the dead returning to join the living, with the latter's perceptions of spacetime evolving to join the former's, and while there was never a lot of detail as to what the implications of that actually were, it seems logical that the denizens of the comic itself had become something like the aloof gods, the readers, able to pause and glimpse the panels we always know are there, drawing the characters out so that they are like Alan Moore, and those reading comics written by him - delighted in mechanics, constructs. Looking at all the world and its glory as students. Mapping, charting, sometimes gazing into a microscope, maybe at the superhero genre, maybe at literary characters and devices. Always from Outside.

That's not Grant Morrison's take. He's Inside. He's been known to define existence as a single, massice organism, and we and all we know are within. We cannot go out. So, he dives in - many alter egos, Animal Man and all the rest, take him into the comics he writes. He can fairly be said to immerse himself in the superhero genre, fascinated with evolution from the inside - such provides the heart and triumph of All Star Superman in comparison to Moore's first twelve issues of Supreme, its apparent structural model. So when Zatanna -- herself privy to a meeting with Morrisonian overseers -- casts that big final spell, images of past issues jump out at the readers to surround them, as Zatanna's outstretched hands seem to beckon them in, to embrace them. That is Morrison's and Williams' secret 3-D, and the only goddamned comic book Easter Egg I can think of that managed to be thematically substantive.

Now we're in the middle of Final Crisis -- this being a tie-in -- and Morrison is getting ready to take his leave of superhero comics that aren't spelled 'Batman.' He's cited this particular two-issue thing as getting to the 'bedrock' of the superhero story, "and it's why I'm going to have to take a break from superhero stories for a little bit after Final Crisis." This comes after Seven Soldiers' string of ruminations on heroic evolution on the margins, and the early Final Crisis issues' subversion of that theme into Bad Evolution at the hands of wicked creators, evil winning via slither. It makes perfect sense, then, to use good ol' head-piercing 3-D to better drag the reader's eyes into this bottom-floor action, so they might seem to enter the story with Morrison at such a crucial, primal place.

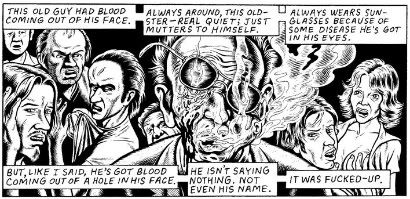

It's not a terribly good comic, really. Morrison hasn't been very effective with the Superman bits in Final Crisis proper, so a lot of the characterization in here, the nuts-and-bolts motivation, feels ad hoc. He's also writing in the style of Final Crisis, which means a generally straightforward sequence of events hammered into a small, dense space, with plenty of knowing understatement. Lots of busy panels, lots of heavy information - you'd think the image of a crazy-eyed Monitor hunched over the leather-caped body of the Nazi Superman variant she's just finished sucking the blood of would score some crazy visual kick, but it's small and tossed off, seemingly to accommodate more words, more solid information. And even granting all this as a continuation of the parent book's style, Morrison also equivocates a bit by dropping in some silly Superman flourishes (see panel above) that tend to prod the book a little ways toward seeming like one of those planned two-issue All Star Superman extensions, albeit an info-heavy, somewhat dour one.

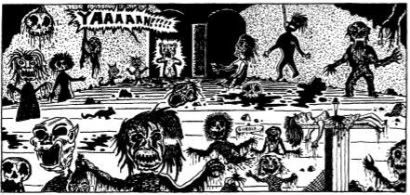

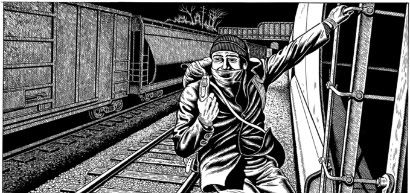

The plot sees Superman recruited to join a team of Supermen from various Earths throughout the Multiverse in order to defeat an awful threat, one that may date all the way back to the dawn of the Monitors. As such, the gang blasts all the way through to Limbo, where forgotten superhero characters stand around doing nothing (Ace the Bat-Hound cameo!), and where A Very Heavy Book sits with all possible stories recorded into it. The metaphor is obvious - enough so that by the time the Misfit Toys begin to escape ("...no, but you see, now they know something can happen [sic], they think anything can happen!"), you'll wonder if Morrison hasn't done all this before in a manner that didn't need to accommodate a turgid creator myth for the DCU's extra-godly class.

Oh, and that 3-D. It's smartly apportioned, kept to Bleed swimming and moments of reality-quaking import; I liked how the style worked as a visual segue into a flashback at the top of the issue. It never really does comic book art much justice, making non-3-D bits all shimmery and odd; I found myself taking the glasses off (careful! don't break them!) whenever I thought I didn't need them, which made my first read-through sort of a chore. I like Doug Mahnke's art fine, although he's fully into slick superhero mode here, with five inkers (himself included) seeming to press in a slightly anonymous quality. He's best with fun little details, like some guy's telescope eyes bending in different directions, one of them toward the reader - it's 3-D!!

It's okay? I was a bit bored. I wonder what sort of ground we'll hit next issue? I think I'll be ready to move on with Morrison; maybe more than ready.

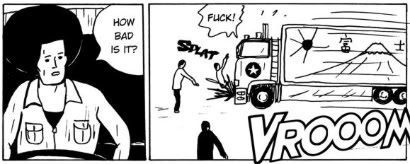

I was damn happy about putting together those glasses, though. So much that I decided to drive home in them, instead of my boring prescription lenses. The cops didn't run me off the highway until I was two miles from home. I pulled myself out of the car and they began firing, without warning.

And their bullets just bounced right off.