"This manga has a positive outlook on life, and so it has been made with as much realism removed as possible."

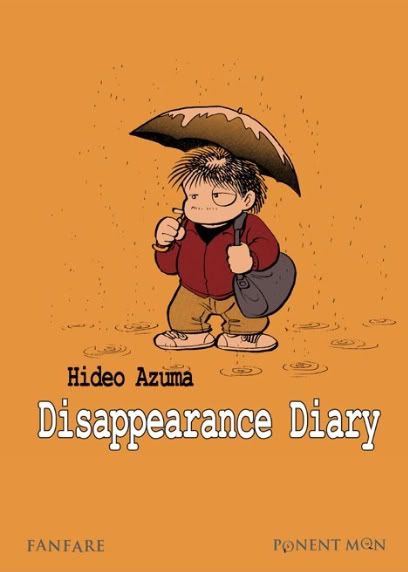

Disappearance Diary

This is the newest release from Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 200 b&w pages for $22.99. It's an acclaimed recent work by longtime manga and doujinshi artist Hideo Azuma, winner of both the Grand Prize for Manga at the 2005 Japan Media Arts Festival and the Grand Prize at the 2006 Osamu Tezuka Cultural Awards.

It's not readily available quite yet. I bought it right out of Fanfare's booth at last weekend's New York Comic Con; owing to Fanfare's distribution troubles, it might not show up in many US stores until late this year, although copies may pop up via UK sources a bit earlier. I think this place even ships free to North America, so keep an eye peeled.

Azuma is yet another one of those influential manga artists who've had basically no work released in English - the situation is especially unfortunate in his case, since this work is an autobiographical comic that would doubtlessly be enhanced by some exposure to the man's body of work. In the 'mainstream' he was noted for humor and sci-fi comics, winning the Seiun Award in 1979 for his Fujōri Nikki. He's apparently done extensive work in autobiographical manga in the small press, and has been long active in doujinshi circles.

And it was from there that he popularized the concept of 'lolicon' -- the eroticisation of young girls -- in manga, from whence much anime and miscellaneous pop cultural fanservice took flower. Granted, Azuma didn't coin the term or anything, nor did he act as some lone, uncaused cause of high school panty flashes and bloody noses. The artist himself, in one of the inevitable 'story of my career' segments of this book, attributes the origins of the stuff to a collision of like-minded interests for which he provided a forum with the fanzine Shiberu.

Fascinatingly, he also characterizes the effort as a reaction to the rise of yaoi in doujinshi circles, which raises a whole host of gender conflict and objectification issues, seeing as how yaoi was both emblematic of the rise of female manga artists as a major force in a formerly male-dominated art form (the 1978 Seiun winner for manga? Keiko Takemiya's To Terra...), and arguably a fetishization of a marginalized subset of the population (homosexual men) for the pleasure of a larger group (heterosexual women).

Did the answer to this phenomena involve a much more powerful group (heterosexual men) focusing their gaze on a larger, less powerful subset of the opposite gender (teenage-and-under women)? I don't know enough to speak with authority, but I do know I'd have liked more reflection on that topic.

That's not what Disappearance Diary is about, though. It has other questions to ponder.

Following a short prelude in which the author drunkenly attempts to hang himself in the woods but winds up falling asleep with the noose around his neck, the book tracks three nasty periods in the life of a man who can't help but vanish from polite company. Events are recounted in a sober, detail-oriented style that brings to mind Kazuichi Hanawa's Doing Time, although Azuma's old-fashioned, blobby-faced art is far brighter, and his construction of each chapter emphasizes absurdities and awkward moments for comedic effect, all the better to juxtapose against the harshness of his subject matter - at times, it's a bit like reading a semi-serious Beetle Bailey graphic novel about Sarge's attempts to drop out of society.

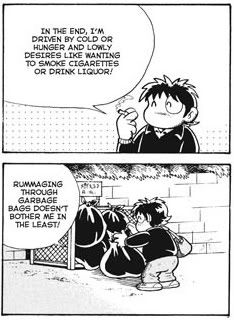

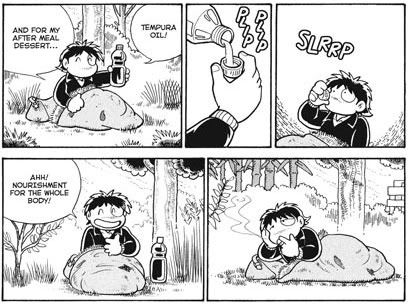

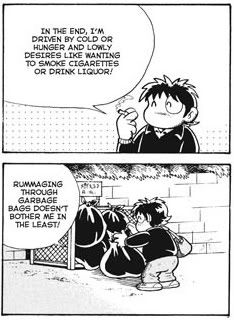

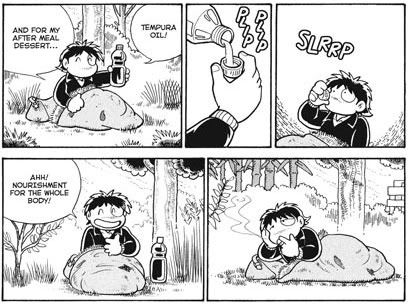

This gives the work a unique tone, one that won't sit well with all readers, I expect. In 1989, Azuma fails to return from a research trip, holing up in the mountains to live without a home, listening to the cartilage in his joints noisily contract as he sleeps in the winter air, eating and drinking and smoking whatever discarded shit he can find. He starts off stealing food from another drifter, but eventually restricts his thievery to books. He cringes at being called a 'beggar,' since he won't beg for anything, but being called a 'bum' is pretty cool. Lots of helpful tips are included for you freegans out there; Our Hero actually winds up gaining weight after establishing a regular supermarket cache, although he does his share of puking.

Most crucially, he shows no remorse, even though he makes it very clear he has a family at home and editors that depend on him. It's Azuma's wife that files the missing person reports that eventually lead the police to haul him back home, but he affords her almost no character in this book. In 1992, Azuma once more winds up running away, this time finding work in pipe fitting under an assumed identity, making new friends and living in a new society, and going so far as to become a cartoonist all over again with his contributions to the company newsletter. And even after he's dragged back home, he persists on keeping up his new life; in one notable instance, he deletes an account of a post-reunion interaction with his wife because "none of this was funny."

Some will find Azuma's self-presentation to be impossibly callous, although I think it's clear this is a deliberate creative choice rather than mere self-absorption. A pair of supplementary interviews -- a giggly, fannish chat with Tori Miki and a 'serious' talk with Kiuchi Maya (the latter of which is literally hidden, like a dvd easter egg, presumably so as not to interfere with the book's aesthetic) -- reveal that Azuma is aware of the effect his actions had on his loved ones, not to mention that his wife did the finishes on the book's art!

Throughout the story there are little reminders, implicit and explicit, that what we're reading is an abridged-for-entertainment account of true events, as if all the pain in the world could be subsumed into wacky gags... or perhaps gags are the better way of making such painful things approachable?

Regardless, a subtext develops from Azuma's creative choices. I think it's natural for the reader to expect a moment of certain realization for the primary character in this sort of book, a point at which he or she can label his or her own actions as 'wrong,' even if it's only some crucial crossing-of-the-line rock-bottom moment ('After I ate that toy poodle without even cooking it, I knew I was sick!'). Often, society at large is thereby affirmed in its existance as the path which all persons ought to stick to on their hike through living ('Now I have a good job and a loving wife, and several unmolested terriers!').

There's none of that in here; stuff just happens with Azuma, and in a fairly merry way, which gives rise to the suggestion that there's nothing implicitly wrong with drastically reasserting one's position in society. The artist acknowledges that he's sick in several ways, suffering from depression and anxiety, and the entire third segment of the book focuses on a 1998 alcohol-related hospitalization, but he neither requests sympathy nor imposes any grand epiphanies upon his narrative. The book does not end; it stops, implying that there will likely be more to follow.

Hardly a new literary device, but it fits in well with Azuma's episodic comedic stylings; just as Beetle will never get an honorable discharge, and Marmaduke will never stop being big and knocking things over (thank heavens), Azuma's inclinations will also endure, their accordant pain coded in art and fleeting in memory, processed into experience. Not a bad approach for an autobiographical comic that's out to entertain in open contempt of 'realism,' since it conveys all the uncertainty of life regardless.

I doubt anyone will be making unequivocal recommendations of this book once it finally pops up in a semi-visible manner - it's too loose in design, too disinclined toward dramatic impact, and its lead character is sure to piss some people off. But I found Azuma's viewpoint to be compelling, and armed with a narrative that fits its take on life as a compilation of punchlines tinged with pain, but still oddly amusing.

This is the newest release from Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 200 b&w pages for $22.99. It's an acclaimed recent work by longtime manga and doujinshi artist Hideo Azuma, winner of both the Grand Prize for Manga at the 2005 Japan Media Arts Festival and the Grand Prize at the 2006 Osamu Tezuka Cultural Awards.

It's not readily available quite yet. I bought it right out of Fanfare's booth at last weekend's New York Comic Con; owing to Fanfare's distribution troubles, it might not show up in many US stores until late this year, although copies may pop up via UK sources a bit earlier. I think this place even ships free to North America, so keep an eye peeled.

Azuma is yet another one of those influential manga artists who've had basically no work released in English - the situation is especially unfortunate in his case, since this work is an autobiographical comic that would doubtlessly be enhanced by some exposure to the man's body of work. In the 'mainstream' he was noted for humor and sci-fi comics, winning the Seiun Award in 1979 for his Fujōri Nikki. He's apparently done extensive work in autobiographical manga in the small press, and has been long active in doujinshi circles.

And it was from there that he popularized the concept of 'lolicon' -- the eroticisation of young girls -- in manga, from whence much anime and miscellaneous pop cultural fanservice took flower. Granted, Azuma didn't coin the term or anything, nor did he act as some lone, uncaused cause of high school panty flashes and bloody noses. The artist himself, in one of the inevitable 'story of my career' segments of this book, attributes the origins of the stuff to a collision of like-minded interests for which he provided a forum with the fanzine Shiberu.

Fascinatingly, he also characterizes the effort as a reaction to the rise of yaoi in doujinshi circles, which raises a whole host of gender conflict and objectification issues, seeing as how yaoi was both emblematic of the rise of female manga artists as a major force in a formerly male-dominated art form (the 1978 Seiun winner for manga? Keiko Takemiya's To Terra...), and arguably a fetishization of a marginalized subset of the population (homosexual men) for the pleasure of a larger group (heterosexual women).

Did the answer to this phenomena involve a much more powerful group (heterosexual men) focusing their gaze on a larger, less powerful subset of the opposite gender (teenage-and-under women)? I don't know enough to speak with authority, but I do know I'd have liked more reflection on that topic.

That's not what Disappearance Diary is about, though. It has other questions to ponder.

Following a short prelude in which the author drunkenly attempts to hang himself in the woods but winds up falling asleep with the noose around his neck, the book tracks three nasty periods in the life of a man who can't help but vanish from polite company. Events are recounted in a sober, detail-oriented style that brings to mind Kazuichi Hanawa's Doing Time, although Azuma's old-fashioned, blobby-faced art is far brighter, and his construction of each chapter emphasizes absurdities and awkward moments for comedic effect, all the better to juxtapose against the harshness of his subject matter - at times, it's a bit like reading a semi-serious Beetle Bailey graphic novel about Sarge's attempts to drop out of society.

This gives the work a unique tone, one that won't sit well with all readers, I expect. In 1989, Azuma fails to return from a research trip, holing up in the mountains to live without a home, listening to the cartilage in his joints noisily contract as he sleeps in the winter air, eating and drinking and smoking whatever discarded shit he can find. He starts off stealing food from another drifter, but eventually restricts his thievery to books. He cringes at being called a 'beggar,' since he won't beg for anything, but being called a 'bum' is pretty cool. Lots of helpful tips are included for you freegans out there; Our Hero actually winds up gaining weight after establishing a regular supermarket cache, although he does his share of puking.

Most crucially, he shows no remorse, even though he makes it very clear he has a family at home and editors that depend on him. It's Azuma's wife that files the missing person reports that eventually lead the police to haul him back home, but he affords her almost no character in this book. In 1992, Azuma once more winds up running away, this time finding work in pipe fitting under an assumed identity, making new friends and living in a new society, and going so far as to become a cartoonist all over again with his contributions to the company newsletter. And even after he's dragged back home, he persists on keeping up his new life; in one notable instance, he deletes an account of a post-reunion interaction with his wife because "none of this was funny."

Some will find Azuma's self-presentation to be impossibly callous, although I think it's clear this is a deliberate creative choice rather than mere self-absorption. A pair of supplementary interviews -- a giggly, fannish chat with Tori Miki and a 'serious' talk with Kiuchi Maya (the latter of which is literally hidden, like a dvd easter egg, presumably so as not to interfere with the book's aesthetic) -- reveal that Azuma is aware of the effect his actions had on his loved ones, not to mention that his wife did the finishes on the book's art!

Throughout the story there are little reminders, implicit and explicit, that what we're reading is an abridged-for-entertainment account of true events, as if all the pain in the world could be subsumed into wacky gags... or perhaps gags are the better way of making such painful things approachable?

Regardless, a subtext develops from Azuma's creative choices. I think it's natural for the reader to expect a moment of certain realization for the primary character in this sort of book, a point at which he or she can label his or her own actions as 'wrong,' even if it's only some crucial crossing-of-the-line rock-bottom moment ('After I ate that toy poodle without even cooking it, I knew I was sick!'). Often, society at large is thereby affirmed in its existance as the path which all persons ought to stick to on their hike through living ('Now I have a good job and a loving wife, and several unmolested terriers!').

There's none of that in here; stuff just happens with Azuma, and in a fairly merry way, which gives rise to the suggestion that there's nothing implicitly wrong with drastically reasserting one's position in society. The artist acknowledges that he's sick in several ways, suffering from depression and anxiety, and the entire third segment of the book focuses on a 1998 alcohol-related hospitalization, but he neither requests sympathy nor imposes any grand epiphanies upon his narrative. The book does not end; it stops, implying that there will likely be more to follow.

Hardly a new literary device, but it fits in well with Azuma's episodic comedic stylings; just as Beetle will never get an honorable discharge, and Marmaduke will never stop being big and knocking things over (thank heavens), Azuma's inclinations will also endure, their accordant pain coded in art and fleeting in memory, processed into experience. Not a bad approach for an autobiographical comic that's out to entertain in open contempt of 'realism,' since it conveys all the uncertainty of life regardless.

I doubt anyone will be making unequivocal recommendations of this book once it finally pops up in a semi-visible manner - it's too loose in design, too disinclined toward dramatic impact, and its lead character is sure to piss some people off. But I found Azuma's viewpoint to be compelling, and armed with a narrative that fits its take on life as a compilation of punchlines tinged with pain, but still oddly amusing.

<< Home