Wait, that bottom one isn't a comic at all...

*There is so much in this world.

REVIEW PILE LIBERATION CAMPAIGN #3

***

24 x 2 (David Chelsea; Top Shelf, 48 pages, $5.00): Any new comics release by Chelsea is cause for celebration - his David Chelsea in Love is one of the great autobiographical comics, and I've never read a thing of his that wasn't visually assured to an astonishing degree. He works mainly in illustration, however; maybe the most prolific he's been sequentially in recent years is through his various 24-Hour Comics, drawn under the gun at an average of one page per hour. It's a fairly wide practice, devised by Scott McCloud, often leading to stripped-down, stream-of-consciousness work, hopefully acting as a useful creative exercise.

This pamphlet collects two of Chelsea's nine (so far) such projects, and they may be the most visually splendid examples of their kind I've seen. Thoughtful too: the first, Everybody Gets it Wrong!, is a tongue-in-cheek broadside against the state of autobiographical comics, advocating the first-person perspective as the only means of staying true to experience, particularly in dream sequences. This leads into a suite of helpful examples, sacrificing exactly none of the artist's Winsor McCay-type panache in the process. The second tale, Sleepless, expands the concept into a full-blown adventure in noirish point-of-view surrealism, luxuriously stippled in a manner that couldn't possibly have been done in 24 hours... yet it was! Don't let the concept put you off - these are supple, worthwhile comics by any measure.

***

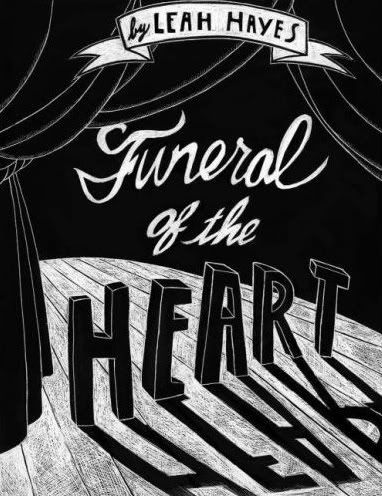

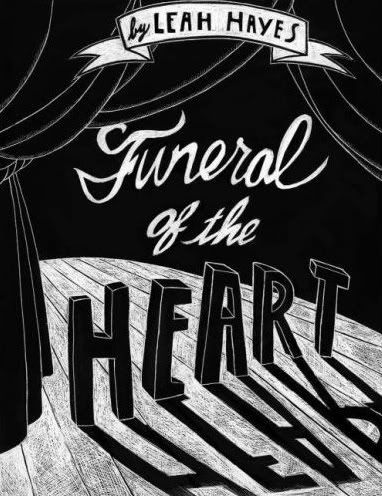

Funeral of the Heart (Leah Hayes; Fantagraphics, 120 pages, $14.95): Billed as a graphic novel, this is actually a quintet of illustrated prose stories by Hayes, an illustrator and member of the band Scary Mansion. The twist is that everything -- from the letters in each word and the logos of each title to the curling lines that form the body of each character -- is handcrafted via scratchboard. This perhaps inevitably results in the prose acting more specifically as design elements than often seen, with whole pages sometimes graced with only three lines, or set off by facing pages of utter blackness; these are short stories, as you might guess.

Hayes works mainly in the mode of melancholic yet blackly fantastical character portraits, with her distressed protagonists often running into allegorical strangeness of some sort. An apologetic couple can no longer swim in their pool after a young boy drowns; later they discover a weird, sparkling clean bathroom underground, only to have the dirt of their guilt pour in. Two young girls are physically joined by their hair, until one of them has enough and breaks away; the other one is sad, but her hair assures some reunion. A man has a job holding down ducks so they can be slaughtered in a special restaurant, and he loves his wife, and he loves the ducks, and he has a nice duck at home and there is so much affection, but then the wife grows ill; feathers fly.

All of it's written in a half-whimsical storybook tone I suppose is meant to collide with Hayes' downcast subject matter and plaintive drawings in a sad-funny way; I found it to be mawkish and simplistic on the whole, if occasionally enlivened by some interesting uses of landscape in the visuals. Only The Needle, a time-spanning account of girls haunted by a death figure, manages any lasting power; it's there that Hayes' fable symbols radiate just beneath the blackness of reality, peeking out sometimes in scratches, obscure but more than capable of effect. The rest of it seems too deliberately drawn in comparison.

***

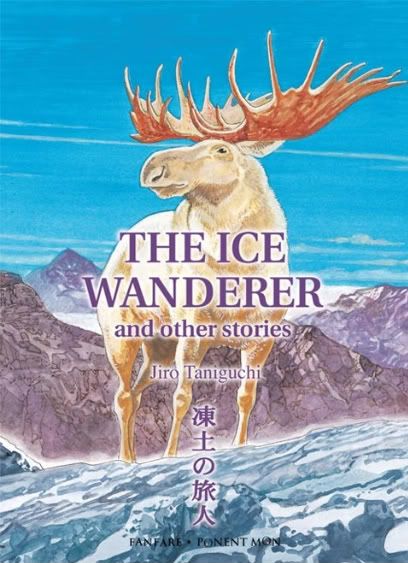

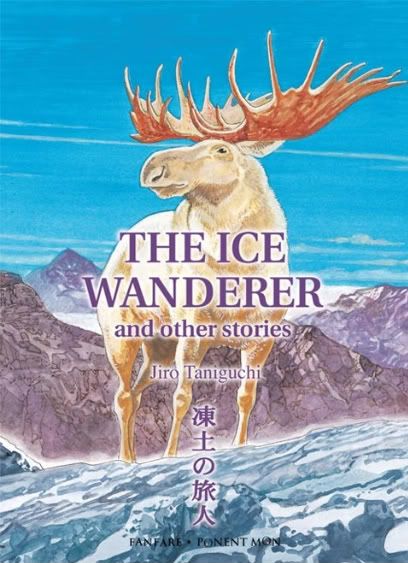

The Ice Wanderer and Other Stories (Jirô Taniguchi; Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 246 pages, $21.99): Here we've got a fat collection of six semi-recent Taniguchi shorts, initially published in various Big Comic-related anthologies between 1994 and 2003, and concerned with men and the wild. Well, except for a (possibly autobiographical) tale of a young aspiring mangaka in the early '70s, which seems to have slipped in due to a passing mention of a periphery character's brother dying at sea. At least it offers some balance - the first half of the collection deals with hard ice, while the second turns to deep water.

Taniguchi's visuals are immaculate as ever -- the newer stories seem to be using digital techniques to render incredibly precise woodland and mountainous regions -- and his zest for period detail gets a great workout in the many time periods on display, but this isn't home to his best writing. Now, we haven't yet gotten English-language access to the man's most acclaimed solo work, so my viewpoint is necessarily skewed as to what his 'best' writing might be, but I've found him to work better either in collaboration with another writer (especially Natsuo Sekikawa of The times of Botchan and Hotel Harbour View) or in such a way that his visuals can shoulder most of the storytelling burden (so, The Walking Man). These comics, on the other hand, tend to portray simple, earnest conflicts and goals that must be met, with time always taken for characters to explain to us the import of discovering the secret graveyard of the whales or killing that damned bear that's haunting the grizzled hero's life.

Probably a good relaxer in the middle of a big anthology (though the less said about a distressingly oedipal coming-of-age heartwarmer the better), and obviously very attractive, but not especially compelling. I think it's telling that the best of this collection's segments are inspired by the works of another writer, Jack London. In the title tale, London himself is a character, trying to avoid hunger in a search for gold while finding inspiration in an old man on a holy quest; here Taniguchi's gift for dramatic realism is at its most potent. And White Wilderness is an expansive comics adaptation of an early portion of London's White Fang, isolating the war between sled team Bill & Henry and a pack of hungry wolves as panorama of lingering doom hovering over opposing forces gone wild and wilder. Says something for collaboration, even if involuntary...

***

Insomnia #3 (of 3) (Matt Broersma; Fantagraphics/Coconino Press, 32 pages, $7.95): This is the gala 25th release of Fanta's and Coconino's Ignatz line of fancy pamphlets (oversized, dustjacketed, sturdy), marking the completion of one of its first series. Granted, you don't need to have read issues #1 and #2 to enjoy this one, since each chapter is essentially its own self-contained thing, but it's here that Broersma pulls together some shared characters into a detailed story that clarifies the series' grand theme, and maybe shines some new light on prior segments.

I do mean detailed - armed with a talkative narrator, dense layouts and a large cast, there's probably more words in this issue than the other two combined. And while I did miss the rhapsodic visuals and minimal character strokes of the artist's earlier (and otherwise stylistically diverse) stories, he proves just as apt with this look at a burnt-out television producer's search for his lost (runaway?) wife, a journey that pulls him deep into the life-as-playacting world that's surrounded his family. You might call it an LA thing, but Broersma's gently-sewn connections to his earlier stories form a web of identities, fluid personalities that need to shift so as to survive the death of dreams, or affect their realization. Sharp stuff, deadpan but poetic; they're all worth reading.

***

Kaiba ep. 1-4 (of 12) (dir. Masaaki Yuasa; Madhouse, approx. 24 min. per, airing on WOWOW): Back when the first episode of this ongoing anime series (from the director of Mind Game) aired, I deemed it "What If... Osamu Tezuka co-founded Métal Hurlant?" Now that we're 1/3 of the way through, I'd like to amend that; the visual style is still as described, but the writing has more or less developed into Ghost in the Shell as a silent era melodrama, crossed with a television chase show.

No, really - set in a world where memories can be extracted from the body in the form of little plugs, thus abrogating the impact of death and seeing much exploitation of the poor by the rich, the show concerns a titular mystery man with a hole in his chest, explosive psychic powers and a busted memory capsule who travels around, sometimes in different bodies, while searching for a lover he can barely recall. Along the way he meets up with various people -- a new batch every episode, naturally -- who try to live decent lives, but mostly suffer a lot.

Kaiba must also stay one step ahead of the awesome Sheriff Vanilla, a fat, horny lawman who either wants to haul Kaiba away or make sweet love to him, depending on which body's in play. Of particular interest is a cute girl body, the shell of a kindly, optimistic lil' street peddler, a dreamer, whose mother sacrificed to buy her pretty boots of hope, but then she gradually sold her memories to put food on the table, and grew cold, cold toward the little girl, and had her body sold and her memories destroyed so as to buy back her own memories, but oh -- oh dear readers -- they only served to remind her of the love she had just, in fact, destroyed!!!

I mean, that's some fucking melodrama there, but it's supercharged with great visual designs and some awesome cartoon effects - my favorite is probably the gadget that lets someone access the memory plug of another by opening up a big thought bubble over the subject's head, which can be literally stretched open and climbed in. The show also has a funny tendency to mix 'modern' or perverse concepts in with its visual style, so as to make, say, someone's body exploding after an epic sex scene more palatable - it might get tinny later on, but the reptile pleasure centers of my brain totally went bananas at the sight of Kaiba dodging a huge slapstick gunshot in bullet-timeish slow motion.

In its best episodes, these elements work in concert to give the show a truly unique feel. And even at its worst, such as an episode where Kaiba assists a pair of anxious brothers searching for Grandma's secret treasure (spoiler: the treasure is LOVE), the style still covers for an awful lot, at least on the first viewing. I find it difficult to complain too much; it's like this show was built for me. And if you happen to enjoy early 20th century Biograph shorts and Osamu Tezuka and Fantastic Planet and ambling Heavy Metal serials about fucking society, man - enjoy your stay in PARADISE.

REVIEW PILE LIBERATION CAMPAIGN #3

***

24 x 2 (David Chelsea; Top Shelf, 48 pages, $5.00): Any new comics release by Chelsea is cause for celebration - his David Chelsea in Love is one of the great autobiographical comics, and I've never read a thing of his that wasn't visually assured to an astonishing degree. He works mainly in illustration, however; maybe the most prolific he's been sequentially in recent years is through his various 24-Hour Comics, drawn under the gun at an average of one page per hour. It's a fairly wide practice, devised by Scott McCloud, often leading to stripped-down, stream-of-consciousness work, hopefully acting as a useful creative exercise.

This pamphlet collects two of Chelsea's nine (so far) such projects, and they may be the most visually splendid examples of their kind I've seen. Thoughtful too: the first, Everybody Gets it Wrong!, is a tongue-in-cheek broadside against the state of autobiographical comics, advocating the first-person perspective as the only means of staying true to experience, particularly in dream sequences. This leads into a suite of helpful examples, sacrificing exactly none of the artist's Winsor McCay-type panache in the process. The second tale, Sleepless, expands the concept into a full-blown adventure in noirish point-of-view surrealism, luxuriously stippled in a manner that couldn't possibly have been done in 24 hours... yet it was! Don't let the concept put you off - these are supple, worthwhile comics by any measure.

***

Funeral of the Heart (Leah Hayes; Fantagraphics, 120 pages, $14.95): Billed as a graphic novel, this is actually a quintet of illustrated prose stories by Hayes, an illustrator and member of the band Scary Mansion. The twist is that everything -- from the letters in each word and the logos of each title to the curling lines that form the body of each character -- is handcrafted via scratchboard. This perhaps inevitably results in the prose acting more specifically as design elements than often seen, with whole pages sometimes graced with only three lines, or set off by facing pages of utter blackness; these are short stories, as you might guess.

Hayes works mainly in the mode of melancholic yet blackly fantastical character portraits, with her distressed protagonists often running into allegorical strangeness of some sort. An apologetic couple can no longer swim in their pool after a young boy drowns; later they discover a weird, sparkling clean bathroom underground, only to have the dirt of their guilt pour in. Two young girls are physically joined by their hair, until one of them has enough and breaks away; the other one is sad, but her hair assures some reunion. A man has a job holding down ducks so they can be slaughtered in a special restaurant, and he loves his wife, and he loves the ducks, and he has a nice duck at home and there is so much affection, but then the wife grows ill; feathers fly.

All of it's written in a half-whimsical storybook tone I suppose is meant to collide with Hayes' downcast subject matter and plaintive drawings in a sad-funny way; I found it to be mawkish and simplistic on the whole, if occasionally enlivened by some interesting uses of landscape in the visuals. Only The Needle, a time-spanning account of girls haunted by a death figure, manages any lasting power; it's there that Hayes' fable symbols radiate just beneath the blackness of reality, peeking out sometimes in scratches, obscure but more than capable of effect. The rest of it seems too deliberately drawn in comparison.

***

The Ice Wanderer and Other Stories (Jirô Taniguchi; Fanfare/Ponent Mon, 246 pages, $21.99): Here we've got a fat collection of six semi-recent Taniguchi shorts, initially published in various Big Comic-related anthologies between 1994 and 2003, and concerned with men and the wild. Well, except for a (possibly autobiographical) tale of a young aspiring mangaka in the early '70s, which seems to have slipped in due to a passing mention of a periphery character's brother dying at sea. At least it offers some balance - the first half of the collection deals with hard ice, while the second turns to deep water.

Taniguchi's visuals are immaculate as ever -- the newer stories seem to be using digital techniques to render incredibly precise woodland and mountainous regions -- and his zest for period detail gets a great workout in the many time periods on display, but this isn't home to his best writing. Now, we haven't yet gotten English-language access to the man's most acclaimed solo work, so my viewpoint is necessarily skewed as to what his 'best' writing might be, but I've found him to work better either in collaboration with another writer (especially Natsuo Sekikawa of The times of Botchan and Hotel Harbour View) or in such a way that his visuals can shoulder most of the storytelling burden (so, The Walking Man). These comics, on the other hand, tend to portray simple, earnest conflicts and goals that must be met, with time always taken for characters to explain to us the import of discovering the secret graveyard of the whales or killing that damned bear that's haunting the grizzled hero's life.

Probably a good relaxer in the middle of a big anthology (though the less said about a distressingly oedipal coming-of-age heartwarmer the better), and obviously very attractive, but not especially compelling. I think it's telling that the best of this collection's segments are inspired by the works of another writer, Jack London. In the title tale, London himself is a character, trying to avoid hunger in a search for gold while finding inspiration in an old man on a holy quest; here Taniguchi's gift for dramatic realism is at its most potent. And White Wilderness is an expansive comics adaptation of an early portion of London's White Fang, isolating the war between sled team Bill & Henry and a pack of hungry wolves as panorama of lingering doom hovering over opposing forces gone wild and wilder. Says something for collaboration, even if involuntary...

***

Insomnia #3 (of 3) (Matt Broersma; Fantagraphics/Coconino Press, 32 pages, $7.95): This is the gala 25th release of Fanta's and Coconino's Ignatz line of fancy pamphlets (oversized, dustjacketed, sturdy), marking the completion of one of its first series. Granted, you don't need to have read issues #1 and #2 to enjoy this one, since each chapter is essentially its own self-contained thing, but it's here that Broersma pulls together some shared characters into a detailed story that clarifies the series' grand theme, and maybe shines some new light on prior segments.

I do mean detailed - armed with a talkative narrator, dense layouts and a large cast, there's probably more words in this issue than the other two combined. And while I did miss the rhapsodic visuals and minimal character strokes of the artist's earlier (and otherwise stylistically diverse) stories, he proves just as apt with this look at a burnt-out television producer's search for his lost (runaway?) wife, a journey that pulls him deep into the life-as-playacting world that's surrounded his family. You might call it an LA thing, but Broersma's gently-sewn connections to his earlier stories form a web of identities, fluid personalities that need to shift so as to survive the death of dreams, or affect their realization. Sharp stuff, deadpan but poetic; they're all worth reading.

***

Kaiba ep. 1-4 (of 12) (dir. Masaaki Yuasa; Madhouse, approx. 24 min. per, airing on WOWOW): Back when the first episode of this ongoing anime series (from the director of Mind Game) aired, I deemed it "What If... Osamu Tezuka co-founded Métal Hurlant?" Now that we're 1/3 of the way through, I'd like to amend that; the visual style is still as described, but the writing has more or less developed into Ghost in the Shell as a silent era melodrama, crossed with a television chase show.

No, really - set in a world where memories can be extracted from the body in the form of little plugs, thus abrogating the impact of death and seeing much exploitation of the poor by the rich, the show concerns a titular mystery man with a hole in his chest, explosive psychic powers and a busted memory capsule who travels around, sometimes in different bodies, while searching for a lover he can barely recall. Along the way he meets up with various people -- a new batch every episode, naturally -- who try to live decent lives, but mostly suffer a lot.

Kaiba must also stay one step ahead of the awesome Sheriff Vanilla, a fat, horny lawman who either wants to haul Kaiba away or make sweet love to him, depending on which body's in play. Of particular interest is a cute girl body, the shell of a kindly, optimistic lil' street peddler, a dreamer, whose mother sacrificed to buy her pretty boots of hope, but then she gradually sold her memories to put food on the table, and grew cold, cold toward the little girl, and had her body sold and her memories destroyed so as to buy back her own memories, but oh -- oh dear readers -- they only served to remind her of the love she had just, in fact, destroyed!!!

I mean, that's some fucking melodrama there, but it's supercharged with great visual designs and some awesome cartoon effects - my favorite is probably the gadget that lets someone access the memory plug of another by opening up a big thought bubble over the subject's head, which can be literally stretched open and climbed in. The show also has a funny tendency to mix 'modern' or perverse concepts in with its visual style, so as to make, say, someone's body exploding after an epic sex scene more palatable - it might get tinny later on, but the reptile pleasure centers of my brain totally went bananas at the sight of Kaiba dodging a huge slapstick gunshot in bullet-timeish slow motion.

In its best episodes, these elements work in concert to give the show a truly unique feel. And even at its worst, such as an episode where Kaiba assists a pair of anxious brothers searching for Grandma's secret treasure (spoiler: the treasure is LOVE), the style still covers for an awful lot, at least on the first viewing. I find it difficult to complain too much; it's like this show was built for me. And if you happen to enjoy early 20th century Biograph shorts and Osamu Tezuka and Fantastic Planet and ambling Heavy Metal serials about fucking society, man - enjoy your stay in PARADISE.

Labels: RPLC

<< Home