"It's everything your grandparents ever told you - and more!"

Abandoned Cars

This should be out sometime this month, a $22.99, 168-page hardcover from Fantagraphics, collecting comics by Tim Lane. It's the first volume of a projected trilogy of story suites, seeing recurring characters sweat and stagger under the canopy of what the author calls the Great American Mythological Drama.

And if that seems like an elusive subject, don't worry - this is the type of book that's prone to explaining things. It lays its plan right out in a fake ad before the table of contents. Every story, every scrap of indicia is devoted to working that grand theme every which way. If that's not enough, there's even an author's afterword that spells it out as best it can, though Lane concedes his theme is a ghost, "an exquisite haunting, manifesting itself as an intuition more than an intellectual awareness." It strikes me as haunting in the manner of beholding a very large structure, something that gets you dizzy and panicked from merely considering its might in contrast to your known and suddenly evident delicacy.

So, all of Lane's stories are stuffed with Americana -- icons and vestiges and scenery -- and all of his characters are moved as players on a gameboard of national myth and dreaming. I can't imagine these collected works having the same impact apart from one another, although virtually all of them come from diverse sources like comics anthologies from editors Glenn Head (Hotwire Comics) and Danny Hellman (Legal Action Comics, Typhon), the St. Louis-based Riverfront Times (wherein the artist had a weekly column titled You Are Here) and Lane's own 2004-05 pamphlet series Happy Hour in America, which I admit I've never heard of until now.

They've all got a good home here - I couldn't find any design credit, but this is a very smartly arranged book, its color endpapers presenting a carnival scene, followed by total blackness (like entering a tent show), with pages then alternating between stark character portraits and the aforementioned theme-setting fake ad (all white and cars and smiles), until a carny barker appears to pitch the book's theme again (in a more allusive manner), and we're off to the stories. 'Full' comics are followed by small strips or illustrated prose vignettes, every tale isolated by black, as if new skits need to be set up, actors hurrying around while you can't see.

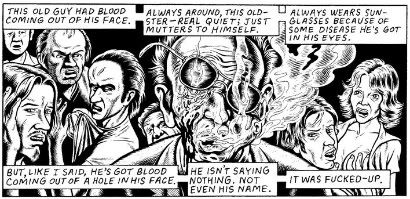

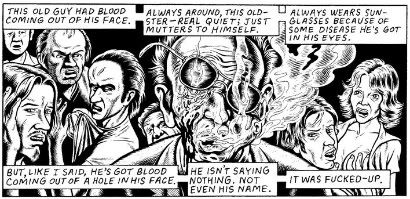

Lane's words and pictures provide different levels of illustration. As can be plainly seen, Lane's visuals are quite heavily influenced by those of Charles Burns (himself no stranger to odd culture), and his narratives proceed with a cadence similarly informed by caption-stuffed pre-Code horror comics. Often there's enough text-based narration that the captions sprout connecting joints so as to guide the reader's eye around the page, like natural growths prone to fusing into a solid mass. Word balloons proliferate rapidly as the visuals seem to harden; Lane does have a flatter style than Burns, one that's good for setting characters against sturdy, detailed backgrounds.

Yet Lane's stories, while leaping in tone from drama to comedy to surrealism to suspense and back again, maintain a distinctly personal focus. Everything in here is essentially a tight character study, and every character is prone to longing after things; we often don't stick around long enough to see if they get what they think they want, although their paths toward some form of personal realization are duly detailed. And sometimes there's not even much of that, although a jaunty "The End" appears at the close of each story, since our time in the tent is limited, after all.

There's an obvious conflict between these unassuming portraits and Lane's visuals, which, whle realistic, wash many panels with stark 'lighting' and present several viewpoints through dramatic perspectives; the result is a knowing juxtaposition of minor human drama and a sort of omniscient grandeur, the Drama of this Great American Myth that surrounds us all.

Lane's stories, taken one by one, vary in effectiveness. There's a fine, elliptical three-page piece in which a man in a bar converses with a guy who's maybe been sent to kill him. A seperate barroom saga explodes the place into an orgy of groping and violence, cars speeding and tree branches thrusting into people's faces as the narrator considers the white noise of his life (aand, frankly, does a good deal of explaining what the drawings are obviously showing) at a mile a minute. It feels busy, almost spoofish.

The more solidly realistic stories tend to be better when kept short, like a three-page bit with a man trying to get a woman to go home with him, becoming more obviously vulnerable as his effort wears on. Elsewhere, a six-page look at a satisfied man's dissolving marriage becomes bogged down in unwieldy narration redundant visuals, when it demands observation and nuance; its continuation later in the book offers little but tinny reversals. When Lane ventures into fantasy, he's more effective when he's funny - a two-part look at an old man's spooked life veers pleasantly from character-driven comedy to tall tale, while the story of a man wounded in love who rams into the life-affirming epiphany of a shimmering forest creature giving birth is about as clumsy as it sounds.

But then, this book's construction discourages the modular reading. Settings and words recur from tale to tale. Multi-part stories partition time periods and settings, lending the project scope. Everything, everything addresses that monster topic in its own way; it accumulates so that even a latecoming two-pager about a man's wife dying and his putting her photograph on her old chair, banal and soppy as it seems, gains some power as punctuation for more substantial looks at American longing and expectation. The same goes for a fact-based comic about Stagger Lee - alone, it presumes an affinity toward the legend surrounding the story, a mystique ineffectively conveyed through its dry recounting of events. But the whole crazy tent show at least affords you some context clues.

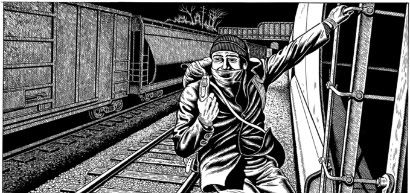

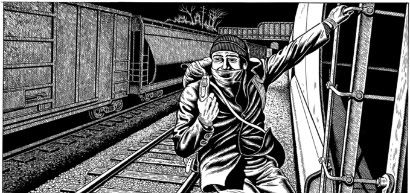

That's a nice Eisner touch with the rising steam up there. Cars are important to this megastory, as Lane notes in that afterword. Or how Lane shows us in a three-part autobiographical story, one of the longest in the book (and the most visually lavish), showing Our Man's attempts at hopping train cars to who knows where in 1994, at the age of 24. It's like a transforming ritual, freeing his spirit by acting iconically, melting into a cold, windy black of a train car to become the Dark Romantic, to sing with Elvis across time, to play the harmonica and face true nothing, and become dramatic like the pictures he'd later draw, and feel the passing tail of the Myth and the Drama.

Yeah, another explanation - but at least Lane fesses up to being another actor among many in this show. And then the sun comes up, and he abandons his car, to get back to the nonplussed living.

It's also just one abandoned car amidst several. Some crash. Some stall. Some get left to run. Some smash into highly symbolic pregnant animals. Some get left at the bar with your hopes for romance. "They offer only superficial and temporary answers to our needs, eventually becoming a skeletal echo of a dream you never stop paying for." Their fates, varied in texture but unified in broad drive, are like the stories in this book, brought together as something singular from sometimes unsatisfying elements. It states its intent, inward and outward; you won't mistake it for something else.

This should be out sometime this month, a $22.99, 168-page hardcover from Fantagraphics, collecting comics by Tim Lane. It's the first volume of a projected trilogy of story suites, seeing recurring characters sweat and stagger under the canopy of what the author calls the Great American Mythological Drama.

And if that seems like an elusive subject, don't worry - this is the type of book that's prone to explaining things. It lays its plan right out in a fake ad before the table of contents. Every story, every scrap of indicia is devoted to working that grand theme every which way. If that's not enough, there's even an author's afterword that spells it out as best it can, though Lane concedes his theme is a ghost, "an exquisite haunting, manifesting itself as an intuition more than an intellectual awareness." It strikes me as haunting in the manner of beholding a very large structure, something that gets you dizzy and panicked from merely considering its might in contrast to your known and suddenly evident delicacy.

So, all of Lane's stories are stuffed with Americana -- icons and vestiges and scenery -- and all of his characters are moved as players on a gameboard of national myth and dreaming. I can't imagine these collected works having the same impact apart from one another, although virtually all of them come from diverse sources like comics anthologies from editors Glenn Head (Hotwire Comics) and Danny Hellman (Legal Action Comics, Typhon), the St. Louis-based Riverfront Times (wherein the artist had a weekly column titled You Are Here) and Lane's own 2004-05 pamphlet series Happy Hour in America, which I admit I've never heard of until now.

They've all got a good home here - I couldn't find any design credit, but this is a very smartly arranged book, its color endpapers presenting a carnival scene, followed by total blackness (like entering a tent show), with pages then alternating between stark character portraits and the aforementioned theme-setting fake ad (all white and cars and smiles), until a carny barker appears to pitch the book's theme again (in a more allusive manner), and we're off to the stories. 'Full' comics are followed by small strips or illustrated prose vignettes, every tale isolated by black, as if new skits need to be set up, actors hurrying around while you can't see.

Lane's words and pictures provide different levels of illustration. As can be plainly seen, Lane's visuals are quite heavily influenced by those of Charles Burns (himself no stranger to odd culture), and his narratives proceed with a cadence similarly informed by caption-stuffed pre-Code horror comics. Often there's enough text-based narration that the captions sprout connecting joints so as to guide the reader's eye around the page, like natural growths prone to fusing into a solid mass. Word balloons proliferate rapidly as the visuals seem to harden; Lane does have a flatter style than Burns, one that's good for setting characters against sturdy, detailed backgrounds.

Yet Lane's stories, while leaping in tone from drama to comedy to surrealism to suspense and back again, maintain a distinctly personal focus. Everything in here is essentially a tight character study, and every character is prone to longing after things; we often don't stick around long enough to see if they get what they think they want, although their paths toward some form of personal realization are duly detailed. And sometimes there's not even much of that, although a jaunty "The End" appears at the close of each story, since our time in the tent is limited, after all.

There's an obvious conflict between these unassuming portraits and Lane's visuals, which, whle realistic, wash many panels with stark 'lighting' and present several viewpoints through dramatic perspectives; the result is a knowing juxtaposition of minor human drama and a sort of omniscient grandeur, the Drama of this Great American Myth that surrounds us all.

Lane's stories, taken one by one, vary in effectiveness. There's a fine, elliptical three-page piece in which a man in a bar converses with a guy who's maybe been sent to kill him. A seperate barroom saga explodes the place into an orgy of groping and violence, cars speeding and tree branches thrusting into people's faces as the narrator considers the white noise of his life (aand, frankly, does a good deal of explaining what the drawings are obviously showing) at a mile a minute. It feels busy, almost spoofish.

The more solidly realistic stories tend to be better when kept short, like a three-page bit with a man trying to get a woman to go home with him, becoming more obviously vulnerable as his effort wears on. Elsewhere, a six-page look at a satisfied man's dissolving marriage becomes bogged down in unwieldy narration redundant visuals, when it demands observation and nuance; its continuation later in the book offers little but tinny reversals. When Lane ventures into fantasy, he's more effective when he's funny - a two-part look at an old man's spooked life veers pleasantly from character-driven comedy to tall tale, while the story of a man wounded in love who rams into the life-affirming epiphany of a shimmering forest creature giving birth is about as clumsy as it sounds.

But then, this book's construction discourages the modular reading. Settings and words recur from tale to tale. Multi-part stories partition time periods and settings, lending the project scope. Everything, everything addresses that monster topic in its own way; it accumulates so that even a latecoming two-pager about a man's wife dying and his putting her photograph on her old chair, banal and soppy as it seems, gains some power as punctuation for more substantial looks at American longing and expectation. The same goes for a fact-based comic about Stagger Lee - alone, it presumes an affinity toward the legend surrounding the story, a mystique ineffectively conveyed through its dry recounting of events. But the whole crazy tent show at least affords you some context clues.

That's a nice Eisner touch with the rising steam up there. Cars are important to this megastory, as Lane notes in that afterword. Or how Lane shows us in a three-part autobiographical story, one of the longest in the book (and the most visually lavish), showing Our Man's attempts at hopping train cars to who knows where in 1994, at the age of 24. It's like a transforming ritual, freeing his spirit by acting iconically, melting into a cold, windy black of a train car to become the Dark Romantic, to sing with Elvis across time, to play the harmonica and face true nothing, and become dramatic like the pictures he'd later draw, and feel the passing tail of the Myth and the Drama.

Yeah, another explanation - but at least Lane fesses up to being another actor among many in this show. And then the sun comes up, and he abandons his car, to get back to the nonplussed living.

It's also just one abandoned car amidst several. Some crash. Some stall. Some get left to run. Some smash into highly symbolic pregnant animals. Some get left at the bar with your hopes for romance. "They offer only superficial and temporary answers to our needs, eventually becoming a skeletal echo of a dream you never stop paying for." Their fates, varied in texture but unified in broad drive, are like the stories in this book, brought together as something singular from sometimes unsatisfying elements. It states its intent, inward and outward; you won't mistake it for something else.

<< Home