"Come On Come On! Remember to Forget to Forget to Remember"

What It Is

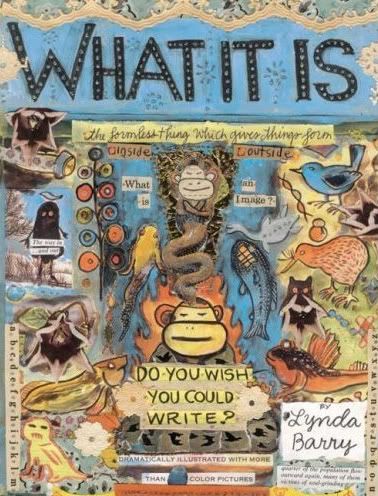

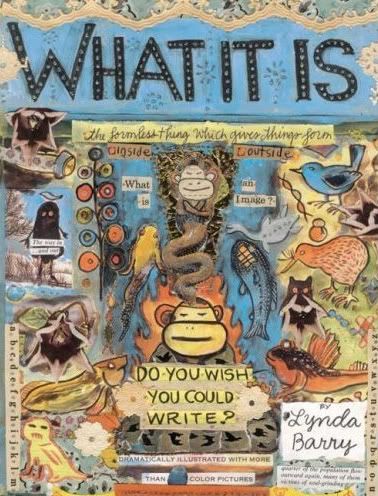

This is the much-anticipated new book from Lynda Barry, her first with publisher Drawn and Quarterly. I don't think it's out in Direct Market stores just yet, but some large bookstores should have it right now. It's a 208-page hardcover, sized at 11" x 8.5", priced at $24.95. You won't easily gloss it over on the shelves.

That's reassuring; Barry may be an experienced, influential figure in alternative comics -- her signature weekly strip, Ernie Pook's Comeek (which D&Q will reprint in five collected volumes starting later this year), has been running for over one quarter of a century -- but she doesn't have a terribly pronounced presence in book form. Most collections of her work are out of print, and even highly-acclaimed recent books like 2002's One! Hundred! Demons! (from Sasquatch Books, collecting material from Salon.com) can be tricky to find offline. But D&Q, fully in spite of its size, excels at getting its projects into a broad range of venues, often with a supple backing of varied media attention.

It'll be interesting to see what those sources make of What It Is, a colorful, sometimes cacophonous mix of 'How To' writing instruction, philosophic text and creative autobiography, adopting the visual attributes of anything that might meld words and pictures, be it comics, collage or activity workpages. Steeped in personal reflection and lessons learned from valued teachers -- not to mention the author's own Writing the Unthinkable seminars -- it's as crisply straightforward in presentation as any student could like, yet as elusive and challenging in certain passages as the questions it confronts, those Barry deems fundamental to the individual human experience.

Memory, imagination, myth, thought, meaning, image - all are addressed, perhaps in so individual a manner that those looking for basic writing instruction from a glance at the cover might find it all unduly digressive, a bit arty for adequate tutoring as to the arts. But I'm not sure how else this book could have read, given Barry's take on the inseparability of creation and being, the impossible beauty of transubstantiating the several species of recollection, the immaterial, into the experiential.

The bulk of the book's space is occupied by a 133-page section titled, appropriately, What It Is. As you can see, the paper stock is blue, the images themselves appear to have been composed on sheets from a yellow notepad, and all of the text is handwritten, with certain words displayed in cursive, just as a typical comic book dialog bubble might set some words in bold. Other elements of the page include drawings, as exuberantly doodled as any Barry has done, and 'found' elements pasted down among the rest. Across the scope of her narrative, Barry suggests the importance of everything we can see that she has done.

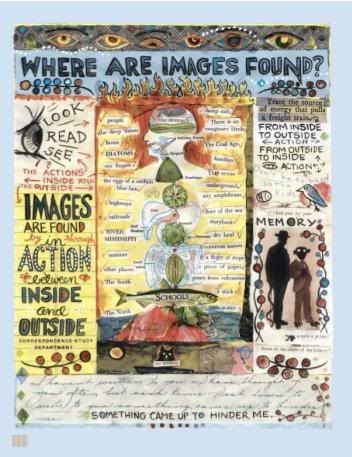

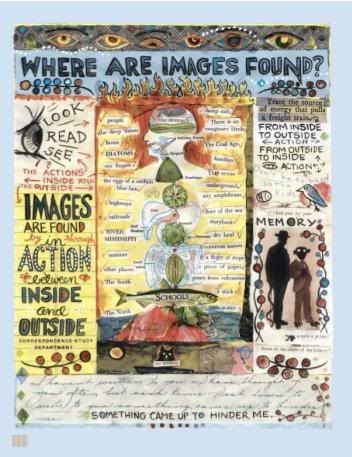

For most of the 'blue' section, the narrative alternates between two modes: (1) text and drawing-heavy narration, tracking some of the author's experiences from childhood forward; and (2) "Essay Questions" illuminated through intensive mixed-media displays, involving bits of old textbooks, altered photographs, childlike scribbles, snatches from a cache of elementary school assignments dating back to the 1920s and other miscellaneous objects. The overall texture is that of a deeply purposeful scrapbook; when Barry opts to plug in a 13-page story that first appeared in McSweeny's, it looks as if she may have literally cut the pages out of copies of the original publication, laying it all down on her yellow base.

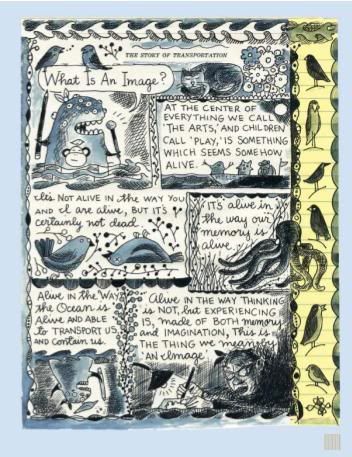

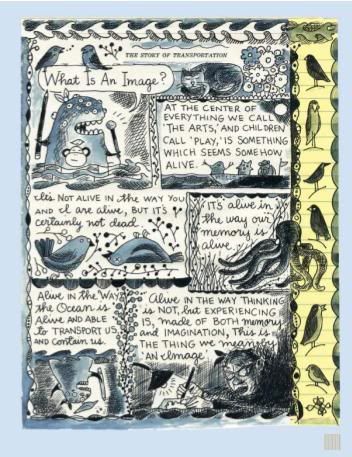

Both modes are autobiographical; that becomes clear very quickly. There's a telling bit later on in the book in which Barry presents some of her initial mixed-media designs for the Penguin Deluxe Classics cover of Little Women she was commissioned to do - her initial plan was rejected by the art director for not looking enough like 'her' work, a reaction she found both funny and sad (I wonder what that art director made of Frank Miller?). As such, Barry's 'mode one' narrative begins with her initial childlike inability to segregate living things from images, which she uses as a springboard for discussing how some images are indeed alive in the manner of memories and imaginings. Images are the base of Barry's concept of 'writing' -- in contrast to events or impressions -- and as the narrative proceeds, realizations and metaphors spring up to accompany the girl's growth.

"We don't create a fantasy world to escape reality, we create it to be able to stay." So declares Barry as she muses on the transportation of reading, which in the uncertainty of recollection can become just as vivid as 'real' experiences. She tells of her favorite mythic monster, the Gorgon, who helped her understand her own mother, although she also explodes the notion into a larger metaphor of passive media consumption -- watching television -- as turning one to stone, both to the effect of pleasurably destroying oscillating life emotions (even providing some creative inspiration!), and freezing the recollected life into a prepared flow of images while rendering the viewer perfectly still. I have to wonder if the reader of a comic would be any less still if the characters could stare out past the fourth wall, but I presume by this understanding that the reader's involvement with filling in the gutters would transport them inside the work.

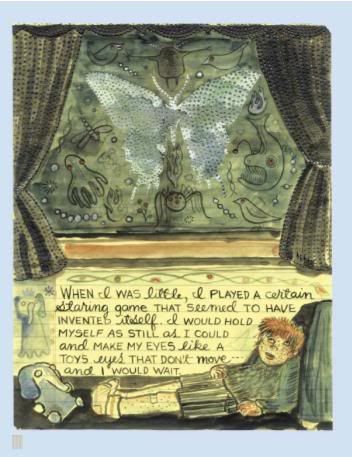

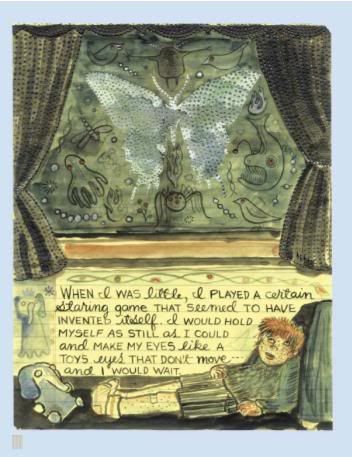

All of this is bolstered by Barry's 'mode two' creations, which aren't so much answers to her omnipresent queries ("We do not know the answers," she remarks up front), as marshallings of how the contours of those questions can be understood through creative work, writing presented as the natural extension of reading. There's an excellent image repeated twice (with some variation) in the book, depicting Barry as a child seated in a darkened room, a square source of light transfixing her - the initial impression is that of a television, but Barry's linework within the light source suggests a scribbly drawing of shapes, that which lays close but cannot immediately be grasped without desire. It's perhaps the best of several visual metaphors at work in a book not lacking for anything of the type.

Connections pile up as the narrative goes on. Barry does not address drawing as drawing-for-comics, but insists on the power of writing by hand: drawing words. This is linked to the concept of childhood 'play,' which can be very much like work to a young kid left alone. But just as kids give up many forms of play as they grow self-conscious to societal standards of behavior, so do people stop creating when confronted with democratic or academic decrees of what 'good' art is; this does not sit well with Barry, whose advocation of creation, writing, is in the form of a personal means of expression best kept far away from the concerns of audience or commerce, in that way that one needn't take the stage to breathe.

Ah, but Barry is a respected, successful artist, one who did eventually revise that book cover! This not unimportant facet of her experience forms the concluding pages of the blue section, in which the eventual demands of art-as-work extends the societal concept of 'good' art into Two Questions the author finds surrounding her work, as she works: "Is this good?" and "Does this suck?" She depicts it as a paralyzing dichotomy, abrogated only by a temporary abandonment of the very concept of 'good' work when actually creating (Marion Milner's On Not Being Able to Paint is duly cited). After all, Barry characterizes her own career as a cartoonist as accidental; to invoke one of her own explanatory tales, writing is like setting your life free from a can, and while fame or fortune or even a living wage cannot be guaranteed, being out of the can is its own powerful joy.

The rest of the book serves to spur action or reflecting regarding what has gone before. There's a 37-page pink section titled Activity Book -- a good portion of which served as D&Q's Free Comic Book Day giveaway for 2007 -- which provides more pointed, exercise-driven instruction from Barry and her cast of characters (a multi-eyed beastie called Sea-Man, a helpful Magic Cephalopod), much of it taking the form of expanding memory points into environments, keeping the hand moving at all times, basic steps to shore up (or establish) the bond between thought and language. A 15-page green section called Let's Make a Free Writing Kit focuses on tools to use in furthering your exercise, and a 22-page orange section, Notes on Notes, serves as both a slightly obscure appendix -- letting the reader see what Barry was doodling while working on other pages -- and a further extension of the artist's always-writing ethos, always personal.

But maybe it's the most appropriate way to 'end' a book that can't have an ending. What It Is surely isn't going to lead anyone into creating a commercially viable or particularly entertaining work, because it aches to address the creative impulse on a more primal level, one of sheer self-satisfaction as a means to assure one's self of simple aliveness. As a result, it can only end with the end of life itself, and can otherwise spread into every evocative and opaque form, neat or unruly. This book is all of that, but it's mostly a success in embodying how emphatic Barry is about her means of creation, and how far inside she's ready to climb.

This is the much-anticipated new book from Lynda Barry, her first with publisher Drawn and Quarterly. I don't think it's out in Direct Market stores just yet, but some large bookstores should have it right now. It's a 208-page hardcover, sized at 11" x 8.5", priced at $24.95. You won't easily gloss it over on the shelves.

That's reassuring; Barry may be an experienced, influential figure in alternative comics -- her signature weekly strip, Ernie Pook's Comeek (which D&Q will reprint in five collected volumes starting later this year), has been running for over one quarter of a century -- but she doesn't have a terribly pronounced presence in book form. Most collections of her work are out of print, and even highly-acclaimed recent books like 2002's One! Hundred! Demons! (from Sasquatch Books, collecting material from Salon.com) can be tricky to find offline. But D&Q, fully in spite of its size, excels at getting its projects into a broad range of venues, often with a supple backing of varied media attention.

It'll be interesting to see what those sources make of What It Is, a colorful, sometimes cacophonous mix of 'How To' writing instruction, philosophic text and creative autobiography, adopting the visual attributes of anything that might meld words and pictures, be it comics, collage or activity workpages. Steeped in personal reflection and lessons learned from valued teachers -- not to mention the author's own Writing the Unthinkable seminars -- it's as crisply straightforward in presentation as any student could like, yet as elusive and challenging in certain passages as the questions it confronts, those Barry deems fundamental to the individual human experience.

Memory, imagination, myth, thought, meaning, image - all are addressed, perhaps in so individual a manner that those looking for basic writing instruction from a glance at the cover might find it all unduly digressive, a bit arty for adequate tutoring as to the arts. But I'm not sure how else this book could have read, given Barry's take on the inseparability of creation and being, the impossible beauty of transubstantiating the several species of recollection, the immaterial, into the experiential.

The bulk of the book's space is occupied by a 133-page section titled, appropriately, What It Is. As you can see, the paper stock is blue, the images themselves appear to have been composed on sheets from a yellow notepad, and all of the text is handwritten, with certain words displayed in cursive, just as a typical comic book dialog bubble might set some words in bold. Other elements of the page include drawings, as exuberantly doodled as any Barry has done, and 'found' elements pasted down among the rest. Across the scope of her narrative, Barry suggests the importance of everything we can see that she has done.

For most of the 'blue' section, the narrative alternates between two modes: (1) text and drawing-heavy narration, tracking some of the author's experiences from childhood forward; and (2) "Essay Questions" illuminated through intensive mixed-media displays, involving bits of old textbooks, altered photographs, childlike scribbles, snatches from a cache of elementary school assignments dating back to the 1920s and other miscellaneous objects. The overall texture is that of a deeply purposeful scrapbook; when Barry opts to plug in a 13-page story that first appeared in McSweeny's, it looks as if she may have literally cut the pages out of copies of the original publication, laying it all down on her yellow base.

Both modes are autobiographical; that becomes clear very quickly. There's a telling bit later on in the book in which Barry presents some of her initial mixed-media designs for the Penguin Deluxe Classics cover of Little Women she was commissioned to do - her initial plan was rejected by the art director for not looking enough like 'her' work, a reaction she found both funny and sad (I wonder what that art director made of Frank Miller?). As such, Barry's 'mode one' narrative begins with her initial childlike inability to segregate living things from images, which she uses as a springboard for discussing how some images are indeed alive in the manner of memories and imaginings. Images are the base of Barry's concept of 'writing' -- in contrast to events or impressions -- and as the narrative proceeds, realizations and metaphors spring up to accompany the girl's growth.

"We don't create a fantasy world to escape reality, we create it to be able to stay." So declares Barry as she muses on the transportation of reading, which in the uncertainty of recollection can become just as vivid as 'real' experiences. She tells of her favorite mythic monster, the Gorgon, who helped her understand her own mother, although she also explodes the notion into a larger metaphor of passive media consumption -- watching television -- as turning one to stone, both to the effect of pleasurably destroying oscillating life emotions (even providing some creative inspiration!), and freezing the recollected life into a prepared flow of images while rendering the viewer perfectly still. I have to wonder if the reader of a comic would be any less still if the characters could stare out past the fourth wall, but I presume by this understanding that the reader's involvement with filling in the gutters would transport them inside the work.

All of this is bolstered by Barry's 'mode two' creations, which aren't so much answers to her omnipresent queries ("We do not know the answers," she remarks up front), as marshallings of how the contours of those questions can be understood through creative work, writing presented as the natural extension of reading. There's an excellent image repeated twice (with some variation) in the book, depicting Barry as a child seated in a darkened room, a square source of light transfixing her - the initial impression is that of a television, but Barry's linework within the light source suggests a scribbly drawing of shapes, that which lays close but cannot immediately be grasped without desire. It's perhaps the best of several visual metaphors at work in a book not lacking for anything of the type.

Connections pile up as the narrative goes on. Barry does not address drawing as drawing-for-comics, but insists on the power of writing by hand: drawing words. This is linked to the concept of childhood 'play,' which can be very much like work to a young kid left alone. But just as kids give up many forms of play as they grow self-conscious to societal standards of behavior, so do people stop creating when confronted with democratic or academic decrees of what 'good' art is; this does not sit well with Barry, whose advocation of creation, writing, is in the form of a personal means of expression best kept far away from the concerns of audience or commerce, in that way that one needn't take the stage to breathe.

Ah, but Barry is a respected, successful artist, one who did eventually revise that book cover! This not unimportant facet of her experience forms the concluding pages of the blue section, in which the eventual demands of art-as-work extends the societal concept of 'good' art into Two Questions the author finds surrounding her work, as she works: "Is this good?" and "Does this suck?" She depicts it as a paralyzing dichotomy, abrogated only by a temporary abandonment of the very concept of 'good' work when actually creating (Marion Milner's On Not Being Able to Paint is duly cited). After all, Barry characterizes her own career as a cartoonist as accidental; to invoke one of her own explanatory tales, writing is like setting your life free from a can, and while fame or fortune or even a living wage cannot be guaranteed, being out of the can is its own powerful joy.

The rest of the book serves to spur action or reflecting regarding what has gone before. There's a 37-page pink section titled Activity Book -- a good portion of which served as D&Q's Free Comic Book Day giveaway for 2007 -- which provides more pointed, exercise-driven instruction from Barry and her cast of characters (a multi-eyed beastie called Sea-Man, a helpful Magic Cephalopod), much of it taking the form of expanding memory points into environments, keeping the hand moving at all times, basic steps to shore up (or establish) the bond between thought and language. A 15-page green section called Let's Make a Free Writing Kit focuses on tools to use in furthering your exercise, and a 22-page orange section, Notes on Notes, serves as both a slightly obscure appendix -- letting the reader see what Barry was doodling while working on other pages -- and a further extension of the artist's always-writing ethos, always personal.

But maybe it's the most appropriate way to 'end' a book that can't have an ending. What It Is surely isn't going to lead anyone into creating a commercially viable or particularly entertaining work, because it aches to address the creative impulse on a more primal level, one of sheer self-satisfaction as a means to assure one's self of simple aliveness. As a result, it can only end with the end of life itself, and can otherwise spread into every evocative and opaque form, neat or unruly. This book is all of that, but it's mostly a success in embodying how emphatic Barry is about her means of creation, and how far inside she's ready to climb.

<< Home