"And you - you've made quite a name for yourself cracking down on the bad boys!"

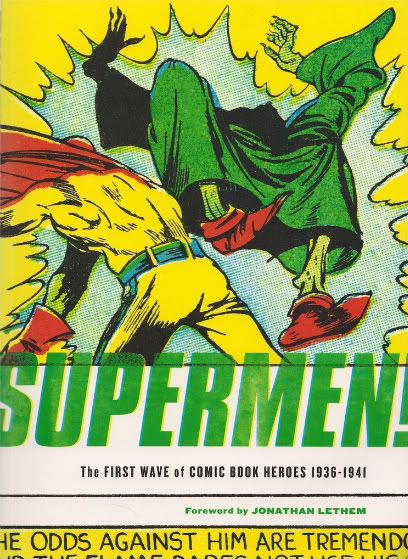

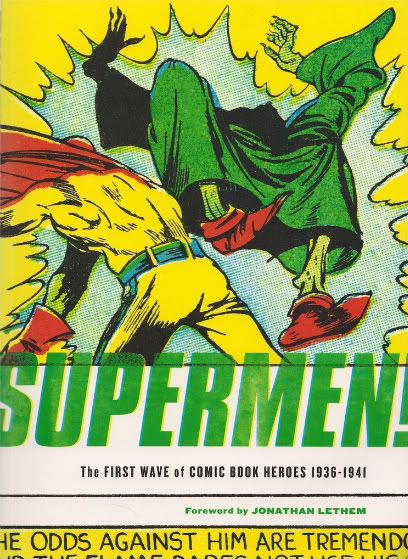

Supermen! The First Wave of Comic Book Heroes 1936-1941

"So, answer the question, even if only in the privacy of your mind: Who was your first? No, go further back even than your 'official' first - recollect, if you can, not the first superhero with whom you consummated your curiosities, but the first who gave you an inkling, the first to stir the curiosities you hadn't know you possessed, the first human outline in a cape flashing through your dawning gaze."

- Jonathan Lethem, from his Foreword

This thing is pretty goddamned amazing.

It's a sampler of 20 pre-WWII superhero stories -- and covers & house ads, bells & whistles -- due out very soon from Fantagraphics, a 192-page color softcover priced at $24.99. Nobody will be able to resist comparisons to the publisher's 2007 superhero reprint hit I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets! The Comics of Fletcher Hanks, although it's somewhat smaller, a good deal thicker, much broader in scope and powered by a different vision, that of editor/designer/producer Greg Sadowski, author of the noted 2002 cartoonist biography B. Krigstein. There's lots of different artists instead of one, none of the backmatter is in cartoon format and, yes, Jonathan Lethem on the topics of curiosities and stirring.

He doesn't stop there either; soon we're deep into a prolonged metaphor concerning Marvel/DC superheroes as elements of a child's circle of acquaintances, from the unequivocal authority of history behind Superman & Batman, mommy & daddy, down through the distanced modernity of the Lee/Kirby Marvel ("something like cool kids who'd lived on your block in the decade before you started playing on the street, and now were off to college or in the army, but their legend persisted") and landing at the feet of Ghost Rider and Luke Cage and (sure!) Omega the Unknown, the new and curious stuff approachable as a peer, if you were a kid when Lethem was.

The point, naturally, is that the world of 'adults' is never so organized as it seems when you're young; grownups are often up to weird shit, and so it goes with grownup culture, like old and moldy comic books. You didn't think Fletcher Hanks acted alone, did you?

He was an individual, sure, but there were many of those at the dawn of the superhero genre; if there's any working thesis to be divined from Sadowski's arrangement -- stories grouped by publisher, with six pages of teensy-font Notes offering a short history of those publishers along with scattered artist bios -- it's that the pre-WWII superheroes were glowing novelties of desperation, forged by artists too young or too troubled to get work in more established medium, stacked up and shipped out to fill the copious waiting pages of a new, pamphlet format, nakedly derivative yet thrilled from a lack of restraining standards.

In other words, of course they were odd and glitchy and fucked-up; they didn't have the experience not to be. Forget American society - there wasn't yet a superhero society to provide direction for the wilder types, left to roam under the vaguely defined (if noticeably enormous) shadow of Superman's success. Or maybe the path of the mighty Flash Gordon from the papers; Sadowski counts space adventurers as superheroes, along with non-powered pulpish crime fighters and turbaned mystics (two of 'em!), since there's no point in being exclusionary with such an undefined age. All he leaves out is any notion of superheroes as Our Modern Myths, preferring to see each (mad)man/woman of mystery as a very specific personality; from their idiosyncrasies, we can know them as the adults Lethem considers.

And hell, what a lineup! Since Sadowski's design playfully groups his 20 selected characters in head-and-shoulders portraits on the title page, and then has them 'mingle' under the table of contents as a super-team, allow me run down the vital stats of just a few members of this Justice League.

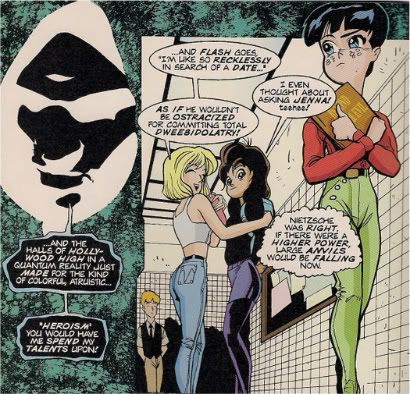

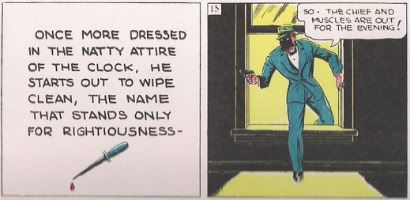

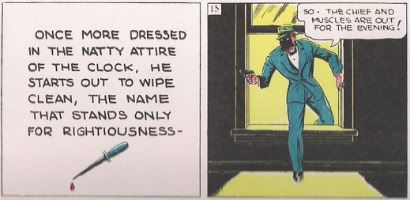

*The Clock!

The Clock is a gritty pulp magazine adventure man whose costume is a black napkin he wears over his face. His secret identity is that of a local drug addict, which is actually pretty clever, and probably only didn't catch on in superheroics from the arrival of the Comics Code.

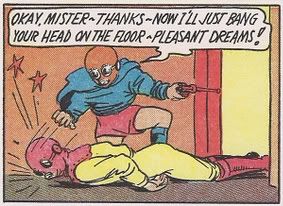

So, the Clock steals money from gangsters and gives to the poor, but since he's outside the law he likes teasing the police too, and really all that keeps his story moving is writer/artist's George E. Brenner's delightfully gritty sense of humor, seeing a gang boss cluck lines like "Now get dressed, - we gotta date with a coupla choras cuties -- an' we won't get to first base if we keep 'em waitin' th' first time!" Also: after the Clock kicks the snot out of a made man and has him write out a confession for his crimes, he makes sure he throws in a clause noting that the confession is made of the guy's free will.

The knife is bloody from carving extra commas.

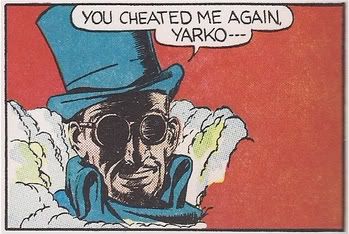

*Yarko the Great!

No less than the famed Will Eisner sends the scowling Yarko and his turban out on what can rightly be called a two-fisted metaphysical journey, by which I mean Yarko travels to the land of the dead in search of a murdered woman and confronts personifications of Pain, Fear and Horror, which Our Hero overcomes by hitting them in the face and/or knocking them off of high ledges. Then he meets Death, who's a goateed hipster in a top hat and solid black Lennon glasses, which he totally wears indoors. Somehow Yarko outsmarts everyone and saves the day, but I presume he'd rather hit them.

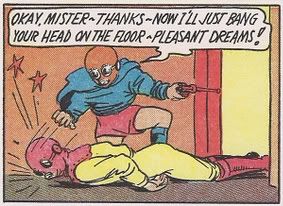

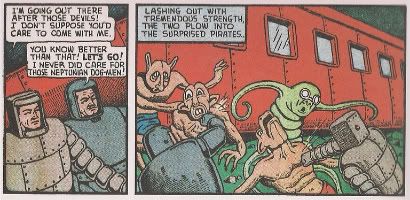

*Fero, Planet Detective!

Apparently host to the first published work by Al Bryant. Fero leads a pretty simple life, rocking an ascot and taking on tough jobs which I suspect invariably center around the recent invasion of Earth by vampires & werewolves from Pluto. This particular outing sees the detective approached by an old man who wants him to find his missing daughter and unravel the enigma of the green light out in the lodge where the gardner got killed.

So the old man takes Fero out to the lodge, and the green light is a werewolf from Pluto who kills the old man and Fero shoots it. Then Fero finds the missing daughter inside the lodge, but a green dwarf shows up and demands to take her away to Pluto, and Fero strangles him. Then another green light appears and it's a vampire from Pluto, which Fero kills by knocking it off of a high ledge. Then the lodge explodes. Another case cracked.

*Dirk the Demon!

Dick the Demon is a happy kid hero in short pants, created and drawn by Bill Everett. As Sadowski notes in the backmatter, Dirk is pretty much the sort of character who'd be a boy sidekick in later comics, but didn't have much commercial success on his own. Dirk is a space hero, accompanying Princess Nemo home to her wedding with some guy. Then they're captured by masked villains, who toss Dirk in a cell, but fortunately he gathers his pluck and lures one of them in, and then knifes him in the heart.

Dirk stays smiling after that, and the scantly-clad princess even flashes him a big grin at adventure's end, although I get the feeling Dirk is a little too young to peel himself away from fatal stabbings and understand her charms! Out of all the comics in here, this is the one that most feels like the lead-in to the next storyline in The Boys. Hell, this could be the first three pages, as-is, not a word changed.

Maybe he'd ease up with a chaperone? Did Terry Lee ever bury a shiv in anyone?

*The Comet!

Of course, then there's adults like the Comet. A creation of the great Jack Cole, the Comet is a guy who injected himself with gas and learned he could soar around, although his eyes also beam out disintegration rays so he has to wear a visor; I've heard of other superheroes with the same problem, although none of them could pull off the stars 'n moons-patterned top.

Anyway, the story in here is an early (the first?) example of the classic 'villains mind-control the hero and make him commit crimes (or commit crimes dressed as him, or something) to ruin his good name.' But since this is nice and early in the genre game -- and Jack Cole (he of the legendary syringe-toward-the-eye in Murder, Morphine and Me) is in charge -- the nasties send the Comet out on a no-fucking-around all-caps RAMPAGE in which he chucks a dude off of a high ledge, steals a bunch of money and kills a whole mess of cops. And I'm not talking 'buried under rubble' or anything; I mean straight-up head shots. No, really:

Those aren't ouch circles at the end of those optic blasts, those are guys' skulls disappearing from their shoulders. Better yet: the publisher is M.L.J. Magazines, future home of Archie. The story ends with the Comet vowing to clear his name, and I presume polite society eventually got over it; he went on to grasp the acclaimed status of first-ever superhero to get killed.

Cole had moved on by that time, driven toward more excellent things. But even in the 1940 of the Comet's murder spree, it was clear that he was a cut above. Those tilted panels, so accomodating of the hero's curled dive, are the first we see of such formal trickery in the book - there's still a palpable, visceral impact to it, a real glee over destruction, coupled with an ecstasy of movement, that red arrow up charging up the hero's spine in the middle panel, launching into the space of that awesome/ridiculous cosmos leotard top and fire pouring out the front, a death ray from a sci-fi comet. Look at his hands. He'll kill them all with those if he has to.

And lest you think it's all campy laffs in here -- and there are more than a few, Lethem spells it out in the Foreword, nothing to be ashamed of -- I can assue you there's many similar moments of impact.

Sure, some stories appear to have been positioned for very specific reasons. The book kicks off with Jerry Siegel's & Joe Shuster's Dr. Mystic (aka: Dr. Occult), their first published superhero and obviously symbolic of both the birth of the Superhero and the oddness/obscurity hiding within even those earliest days - and I'm sure it didn't hurt that the good doctor was a plainclothes Superman look-alike at that time, hair curl and everything (where was he in All Star Superman?).

On the lighter side, I cannot fathom any reason for the inclusion of a totally random chapter of Ken Fitch's & Fred Guardineer's spicily-titled Dan Hastings, save for the halfway-to-dada effect of seeing the titular space hero petition aid from the leaders of Canada, at which point a guy walks in and you kind of pause, because you can't really tell if it's an impossibly horrible racist caricature or a literal creature from beyond the stars, and then you realize that it probably doesn't matter, and luckily the chapter closes on that.

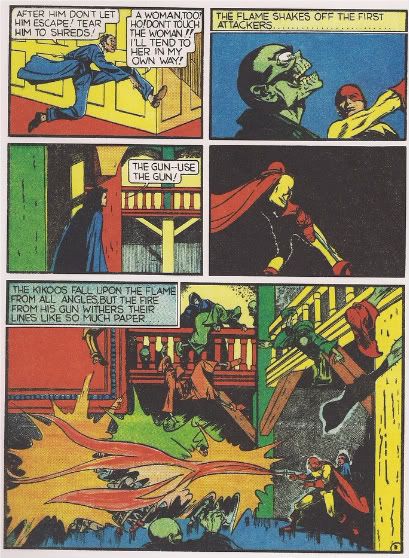

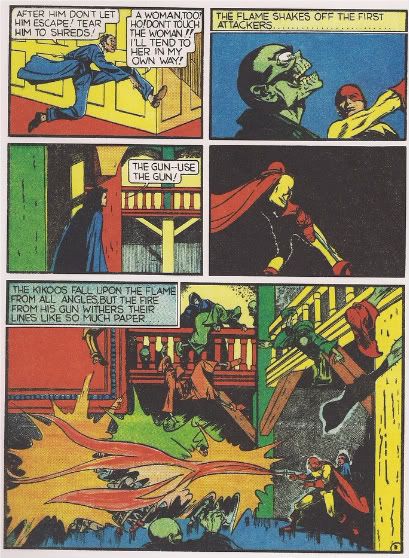

But then, elsewhere, you run into something bona fied odd and striking like an outing for Will Eisner's & Lou Fine's The Flame, wherein a villain has built a small army from a weird native tribe with thin green skin and pliable minds, and everything takes place at night and there's whipping in a castle dungeon, and the hero is a red-yellow suit with a gun that spits graceful flames, and there's pages like:

That is something. From the galloping cartoon nasty in panel #1 -- disturbingly stiff and coughing sexual threats -- to the stony posed close-up of panel #2, then the woman somewhere else, far off, then he reaches for his gun and the whole. world. stops. and explodes as he spins around on the bottom half of the page, god damn. It's a mug's game to try and evaluate the colors in comics this old as anything totally in the artist's control -- usually anonymous souls at the printer just tried to get it ok -- but Will & Lou were blessed on this one. Never mind that the story, once you stop and think about it, is essentially a glass raised toward paternalistic oversight of inferior, ignorant cultures - the visuals just absorb your disquiet, making it all the more itchy and bleak.

Fletcher Hanks is around too, speaking of blessed colors and bleakness, and while his two included stories may seem gratuitous, seeing as how both are slated to be reprinted again in this summer's second all-Hanks omnibus from Fantagraphics & Paul Karasik (the oft-seen online Fantomah story is even the one that contains the book's title, You Shall Die By Your Own Evil Creation!), their presence is kind of fitting anyway; the success of the first Hanks book probably helped a bit with getting this collection published, after all, and now the newer, wider survey can afford Hanks' work some context, treating it as the product of a time that perhaps couldn't help but allow for strange superhero comic visions, like that of Rodan-sized Venusian vultures descending on a European battlefield (it was 1940) to feast freely on combatants.

Er, vultures aren't scavengers on Venus, I guess.

Also worthwhile is the chance to compare the likes of Hanks with equally curious visualists. Basil Wolverton may be acknowleged as a humor great, but his included Spacehawk adventure is a marvel of seething creativity (as Lethem puts it, "each panel like some uncanny rebus, all surfaces stirring from beneath with some incompletely disclosed or acknowledged emotional disquiet, a barely-sublimated mystical Freudian dream"), setting stolid human figures against masses of alien textures and spaghetti 'n meatballs monsters, not quite cooked yet; it probably benefits from Wolverton's eventual association with Mad, and Mad's effect on the '60s underground, since it rather looks more like some underground genre hound's homage to a Golden Age superperson sci-fi comic than an actual product of its time.

But then, that's an appeal of the sampler: matching up works that might play tricks with their influence (however many generations removed) with equally curious, frozen-in-time works, and establishing both as products of the same time, and similar circumstances.

That can all go to hell if the samples themselves are poorly selected, of course. I've read some clunky, overwritten Golden Age superhero stories, and the most boring of them can kill your interest in reading anything stone dead in no time flat. But while there's slow spots in here -- Gardner Fox's & Ogden Whitney's the Skyman embarks on an aimless war against all comers that drags on for 11 long pages, in spite of Whitney's fun, bulky character design -- Sadowski does a remarkable job keeping things lively.

Big, bleeding cover art and barking ads interject themselves at just the right time, with any dull moment quickly counterbalanced by someone like Marvelo, Monarch of Magicians marching in to establish the superhero-as-dickhead archetype, changing rude people to hogs and bringing a huge statue of George Washington to life to lecture gangsters on proper citizenship and walk them to prison. Then he tries to drive the head gangsters insane, because he fucking can. "Kalora!"

That's Jack Cole again, up above; he's got the most pieces in here, three, because he's the best. The Claw rips down a ton of NYC skyscrapers in that one, but the Daredevil (no, not that one) survives by jumping off a plunging ledge at just the right moment and suits up to take him on in what's two or so steps away from a fully comedic Plastic Man opus. We're talking dynamite-down-the-throat silly, but bodies getting crushed so they bleed. The Claw is such mannered Yellow Scare he doesn't look so much like a hateful caricature as a guy possessed by a culturally insensitive ancestor of the Venom symbiote.

Oh, it's still racist as hell, sure; there's a fair amount of that in here. But in positioning this particular clash near the end of the book, aside from saving the best for the final quarter, Sadowski conveys the congealing of superhero tropes; the racial terror of the Claw (himself the first big bad to star in a comic) becomes sunk into the pomp of supervillain superciliousness, even as he and the Daredevil engage in an especially high-profile hero-villain throwdown, with massive property damage and the nasty escaping in a poof of smoke to terrorize the world again, and again, and again, and again.

The Daredevil grins at the end, right at the reader, in the last panel. "Well, folks, it looks like we can breathe easier for awhile - but if I know the Claw, he'll be back for revenge. - And when he does return, this little scrap will seem like a Sunday school picnic!" New York is in ruins, and nobody cares. Get ready to amp it up. Get ready.

Get ready for Captain America. Get ready for Pearl Harbor. The book's final story finally teams Joe Simon & Jack Kirby, on Blue Bolt, two months before the debut of Captain America. It bookends the Siegel & Shuster piece at the beginning, odd stuff by known figures, just an inch or two away from a legendary breakthrough. But the end is really the end; Sadowski sees as the birth of Cap as the dawn of the WWII era in superhero comics, at which time the genre would adopt a broadly martial posture in the name of propoganda, thus becoming domesticated in a way. Falling in line. Lethem's teenagers going away to military school. The dawning of adulthood.

There's no blanket dismissals, mind you. No gnashing of teeth over how superheroes were never the same. It's not that kind of book. No, what happens is, we're shown what happened. That the first era was over, though greater and more Golden sales were to come. The aesthetic densened, the atoms slowed. Signs of condensation. Fletcher Hanks would never have made it then. There were things to be, instead of just things in being. It's all right, it happens to everyone. We have books like this to remind us. Books to get you fired up, to get wanting to draw this stuff. To recreate the Big Bang, collide some particles. Restart. Remember.

God, no wonder so many people starting reading these things, this genre.

Remember, remember.

"So, answer the question, even if only in the privacy of your mind: Who was your first? No, go further back even than your 'official' first - recollect, if you can, not the first superhero with whom you consummated your curiosities, but the first who gave you an inkling, the first to stir the curiosities you hadn't know you possessed, the first human outline in a cape flashing through your dawning gaze."

- Jonathan Lethem, from his Foreword

This thing is pretty goddamned amazing.

It's a sampler of 20 pre-WWII superhero stories -- and covers & house ads, bells & whistles -- due out very soon from Fantagraphics, a 192-page color softcover priced at $24.99. Nobody will be able to resist comparisons to the publisher's 2007 superhero reprint hit I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets! The Comics of Fletcher Hanks, although it's somewhat smaller, a good deal thicker, much broader in scope and powered by a different vision, that of editor/designer/producer Greg Sadowski, author of the noted 2002 cartoonist biography B. Krigstein. There's lots of different artists instead of one, none of the backmatter is in cartoon format and, yes, Jonathan Lethem on the topics of curiosities and stirring.

He doesn't stop there either; soon we're deep into a prolonged metaphor concerning Marvel/DC superheroes as elements of a child's circle of acquaintances, from the unequivocal authority of history behind Superman & Batman, mommy & daddy, down through the distanced modernity of the Lee/Kirby Marvel ("something like cool kids who'd lived on your block in the decade before you started playing on the street, and now were off to college or in the army, but their legend persisted") and landing at the feet of Ghost Rider and Luke Cage and (sure!) Omega the Unknown, the new and curious stuff approachable as a peer, if you were a kid when Lethem was.

The point, naturally, is that the world of 'adults' is never so organized as it seems when you're young; grownups are often up to weird shit, and so it goes with grownup culture, like old and moldy comic books. You didn't think Fletcher Hanks acted alone, did you?

He was an individual, sure, but there were many of those at the dawn of the superhero genre; if there's any working thesis to be divined from Sadowski's arrangement -- stories grouped by publisher, with six pages of teensy-font Notes offering a short history of those publishers along with scattered artist bios -- it's that the pre-WWII superheroes were glowing novelties of desperation, forged by artists too young or too troubled to get work in more established medium, stacked up and shipped out to fill the copious waiting pages of a new, pamphlet format, nakedly derivative yet thrilled from a lack of restraining standards.

In other words, of course they were odd and glitchy and fucked-up; they didn't have the experience not to be. Forget American society - there wasn't yet a superhero society to provide direction for the wilder types, left to roam under the vaguely defined (if noticeably enormous) shadow of Superman's success. Or maybe the path of the mighty Flash Gordon from the papers; Sadowski counts space adventurers as superheroes, along with non-powered pulpish crime fighters and turbaned mystics (two of 'em!), since there's no point in being exclusionary with such an undefined age. All he leaves out is any notion of superheroes as Our Modern Myths, preferring to see each (mad)man/woman of mystery as a very specific personality; from their idiosyncrasies, we can know them as the adults Lethem considers.

And hell, what a lineup! Since Sadowski's design playfully groups his 20 selected characters in head-and-shoulders portraits on the title page, and then has them 'mingle' under the table of contents as a super-team, allow me run down the vital stats of just a few members of this Justice League.

*The Clock!

The Clock is a gritty pulp magazine adventure man whose costume is a black napkin he wears over his face. His secret identity is that of a local drug addict, which is actually pretty clever, and probably only didn't catch on in superheroics from the arrival of the Comics Code.

So, the Clock steals money from gangsters and gives to the poor, but since he's outside the law he likes teasing the police too, and really all that keeps his story moving is writer/artist's George E. Brenner's delightfully gritty sense of humor, seeing a gang boss cluck lines like "Now get dressed, - we gotta date with a coupla choras cuties -- an' we won't get to first base if we keep 'em waitin' th' first time!" Also: after the Clock kicks the snot out of a made man and has him write out a confession for his crimes, he makes sure he throws in a clause noting that the confession is made of the guy's free will.

The knife is bloody from carving extra commas.

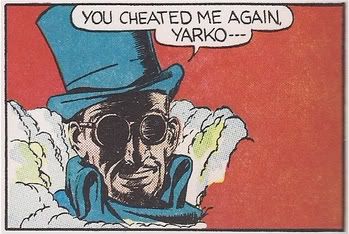

*Yarko the Great!

No less than the famed Will Eisner sends the scowling Yarko and his turban out on what can rightly be called a two-fisted metaphysical journey, by which I mean Yarko travels to the land of the dead in search of a murdered woman and confronts personifications of Pain, Fear and Horror, which Our Hero overcomes by hitting them in the face and/or knocking them off of high ledges. Then he meets Death, who's a goateed hipster in a top hat and solid black Lennon glasses, which he totally wears indoors. Somehow Yarko outsmarts everyone and saves the day, but I presume he'd rather hit them.

*Fero, Planet Detective!

Apparently host to the first published work by Al Bryant. Fero leads a pretty simple life, rocking an ascot and taking on tough jobs which I suspect invariably center around the recent invasion of Earth by vampires & werewolves from Pluto. This particular outing sees the detective approached by an old man who wants him to find his missing daughter and unravel the enigma of the green light out in the lodge where the gardner got killed.

So the old man takes Fero out to the lodge, and the green light is a werewolf from Pluto who kills the old man and Fero shoots it. Then Fero finds the missing daughter inside the lodge, but a green dwarf shows up and demands to take her away to Pluto, and Fero strangles him. Then another green light appears and it's a vampire from Pluto, which Fero kills by knocking it off of a high ledge. Then the lodge explodes. Another case cracked.

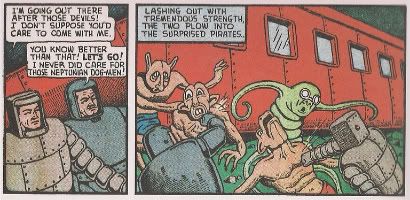

*Dirk the Demon!

Dick the Demon is a happy kid hero in short pants, created and drawn by Bill Everett. As Sadowski notes in the backmatter, Dirk is pretty much the sort of character who'd be a boy sidekick in later comics, but didn't have much commercial success on his own. Dirk is a space hero, accompanying Princess Nemo home to her wedding with some guy. Then they're captured by masked villains, who toss Dirk in a cell, but fortunately he gathers his pluck and lures one of them in, and then knifes him in the heart.

Dirk stays smiling after that, and the scantly-clad princess even flashes him a big grin at adventure's end, although I get the feeling Dirk is a little too young to peel himself away from fatal stabbings and understand her charms! Out of all the comics in here, this is the one that most feels like the lead-in to the next storyline in The Boys. Hell, this could be the first three pages, as-is, not a word changed.

Maybe he'd ease up with a chaperone? Did Terry Lee ever bury a shiv in anyone?

*The Comet!

Of course, then there's adults like the Comet. A creation of the great Jack Cole, the Comet is a guy who injected himself with gas and learned he could soar around, although his eyes also beam out disintegration rays so he has to wear a visor; I've heard of other superheroes with the same problem, although none of them could pull off the stars 'n moons-patterned top.

Anyway, the story in here is an early (the first?) example of the classic 'villains mind-control the hero and make him commit crimes (or commit crimes dressed as him, or something) to ruin his good name.' But since this is nice and early in the genre game -- and Jack Cole (he of the legendary syringe-toward-the-eye in Murder, Morphine and Me) is in charge -- the nasties send the Comet out on a no-fucking-around all-caps RAMPAGE in which he chucks a dude off of a high ledge, steals a bunch of money and kills a whole mess of cops. And I'm not talking 'buried under rubble' or anything; I mean straight-up head shots. No, really:

Those aren't ouch circles at the end of those optic blasts, those are guys' skulls disappearing from their shoulders. Better yet: the publisher is M.L.J. Magazines, future home of Archie. The story ends with the Comet vowing to clear his name, and I presume polite society eventually got over it; he went on to grasp the acclaimed status of first-ever superhero to get killed.

Cole had moved on by that time, driven toward more excellent things. But even in the 1940 of the Comet's murder spree, it was clear that he was a cut above. Those tilted panels, so accomodating of the hero's curled dive, are the first we see of such formal trickery in the book - there's still a palpable, visceral impact to it, a real glee over destruction, coupled with an ecstasy of movement, that red arrow up charging up the hero's spine in the middle panel, launching into the space of that awesome/ridiculous cosmos leotard top and fire pouring out the front, a death ray from a sci-fi comet. Look at his hands. He'll kill them all with those if he has to.

And lest you think it's all campy laffs in here -- and there are more than a few, Lethem spells it out in the Foreword, nothing to be ashamed of -- I can assue you there's many similar moments of impact.

Sure, some stories appear to have been positioned for very specific reasons. The book kicks off with Jerry Siegel's & Joe Shuster's Dr. Mystic (aka: Dr. Occult), their first published superhero and obviously symbolic of both the birth of the Superhero and the oddness/obscurity hiding within even those earliest days - and I'm sure it didn't hurt that the good doctor was a plainclothes Superman look-alike at that time, hair curl and everything (where was he in All Star Superman?).

On the lighter side, I cannot fathom any reason for the inclusion of a totally random chapter of Ken Fitch's & Fred Guardineer's spicily-titled Dan Hastings, save for the halfway-to-dada effect of seeing the titular space hero petition aid from the leaders of Canada, at which point a guy walks in and you kind of pause, because you can't really tell if it's an impossibly horrible racist caricature or a literal creature from beyond the stars, and then you realize that it probably doesn't matter, and luckily the chapter closes on that.

But then, elsewhere, you run into something bona fied odd and striking like an outing for Will Eisner's & Lou Fine's The Flame, wherein a villain has built a small army from a weird native tribe with thin green skin and pliable minds, and everything takes place at night and there's whipping in a castle dungeon, and the hero is a red-yellow suit with a gun that spits graceful flames, and there's pages like:

That is something. From the galloping cartoon nasty in panel #1 -- disturbingly stiff and coughing sexual threats -- to the stony posed close-up of panel #2, then the woman somewhere else, far off, then he reaches for his gun and the whole. world. stops. and explodes as he spins around on the bottom half of the page, god damn. It's a mug's game to try and evaluate the colors in comics this old as anything totally in the artist's control -- usually anonymous souls at the printer just tried to get it ok -- but Will & Lou were blessed on this one. Never mind that the story, once you stop and think about it, is essentially a glass raised toward paternalistic oversight of inferior, ignorant cultures - the visuals just absorb your disquiet, making it all the more itchy and bleak.

Fletcher Hanks is around too, speaking of blessed colors and bleakness, and while his two included stories may seem gratuitous, seeing as how both are slated to be reprinted again in this summer's second all-Hanks omnibus from Fantagraphics & Paul Karasik (the oft-seen online Fantomah story is even the one that contains the book's title, You Shall Die By Your Own Evil Creation!), their presence is kind of fitting anyway; the success of the first Hanks book probably helped a bit with getting this collection published, after all, and now the newer, wider survey can afford Hanks' work some context, treating it as the product of a time that perhaps couldn't help but allow for strange superhero comic visions, like that of Rodan-sized Venusian vultures descending on a European battlefield (it was 1940) to feast freely on combatants.

Er, vultures aren't scavengers on Venus, I guess.

Also worthwhile is the chance to compare the likes of Hanks with equally curious visualists. Basil Wolverton may be acknowleged as a humor great, but his included Spacehawk adventure is a marvel of seething creativity (as Lethem puts it, "each panel like some uncanny rebus, all surfaces stirring from beneath with some incompletely disclosed or acknowledged emotional disquiet, a barely-sublimated mystical Freudian dream"), setting stolid human figures against masses of alien textures and spaghetti 'n meatballs monsters, not quite cooked yet; it probably benefits from Wolverton's eventual association with Mad, and Mad's effect on the '60s underground, since it rather looks more like some underground genre hound's homage to a Golden Age superperson sci-fi comic than an actual product of its time.

But then, that's an appeal of the sampler: matching up works that might play tricks with their influence (however many generations removed) with equally curious, frozen-in-time works, and establishing both as products of the same time, and similar circumstances.

That can all go to hell if the samples themselves are poorly selected, of course. I've read some clunky, overwritten Golden Age superhero stories, and the most boring of them can kill your interest in reading anything stone dead in no time flat. But while there's slow spots in here -- Gardner Fox's & Ogden Whitney's the Skyman embarks on an aimless war against all comers that drags on for 11 long pages, in spite of Whitney's fun, bulky character design -- Sadowski does a remarkable job keeping things lively.

Big, bleeding cover art and barking ads interject themselves at just the right time, with any dull moment quickly counterbalanced by someone like Marvelo, Monarch of Magicians marching in to establish the superhero-as-dickhead archetype, changing rude people to hogs and bringing a huge statue of George Washington to life to lecture gangsters on proper citizenship and walk them to prison. Then he tries to drive the head gangsters insane, because he fucking can. "Kalora!"

That's Jack Cole again, up above; he's got the most pieces in here, three, because he's the best. The Claw rips down a ton of NYC skyscrapers in that one, but the Daredevil (no, not that one) survives by jumping off a plunging ledge at just the right moment and suits up to take him on in what's two or so steps away from a fully comedic Plastic Man opus. We're talking dynamite-down-the-throat silly, but bodies getting crushed so they bleed. The Claw is such mannered Yellow Scare he doesn't look so much like a hateful caricature as a guy possessed by a culturally insensitive ancestor of the Venom symbiote.

Oh, it's still racist as hell, sure; there's a fair amount of that in here. But in positioning this particular clash near the end of the book, aside from saving the best for the final quarter, Sadowski conveys the congealing of superhero tropes; the racial terror of the Claw (himself the first big bad to star in a comic) becomes sunk into the pomp of supervillain superciliousness, even as he and the Daredevil engage in an especially high-profile hero-villain throwdown, with massive property damage and the nasty escaping in a poof of smoke to terrorize the world again, and again, and again, and again.

The Daredevil grins at the end, right at the reader, in the last panel. "Well, folks, it looks like we can breathe easier for awhile - but if I know the Claw, he'll be back for revenge. - And when he does return, this little scrap will seem like a Sunday school picnic!" New York is in ruins, and nobody cares. Get ready to amp it up. Get ready.

Get ready for Captain America. Get ready for Pearl Harbor. The book's final story finally teams Joe Simon & Jack Kirby, on Blue Bolt, two months before the debut of Captain America. It bookends the Siegel & Shuster piece at the beginning, odd stuff by known figures, just an inch or two away from a legendary breakthrough. But the end is really the end; Sadowski sees as the birth of Cap as the dawn of the WWII era in superhero comics, at which time the genre would adopt a broadly martial posture in the name of propoganda, thus becoming domesticated in a way. Falling in line. Lethem's teenagers going away to military school. The dawning of adulthood.

There's no blanket dismissals, mind you. No gnashing of teeth over how superheroes were never the same. It's not that kind of book. No, what happens is, we're shown what happened. That the first era was over, though greater and more Golden sales were to come. The aesthetic densened, the atoms slowed. Signs of condensation. Fletcher Hanks would never have made it then. There were things to be, instead of just things in being. It's all right, it happens to everyone. We have books like this to remind us. Books to get you fired up, to get wanting to draw this stuff. To recreate the Big Bang, collide some particles. Restart. Remember.

God, no wonder so many people starting reading these things, this genre.

Remember, remember.