Movies to Comics - New Direction, Same Result

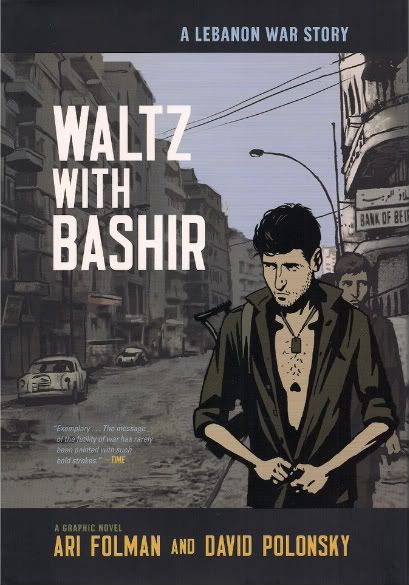

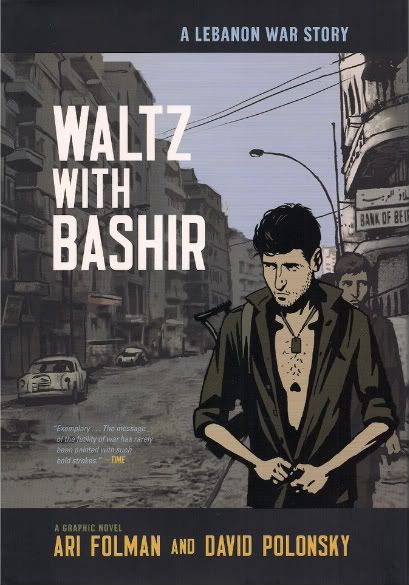

Waltz with Bashir

This should be out very soon. It's the comics version of a high-profile 2008 animated film, the first from Israel to debut in theaters, I think. I'm sure you've heard of it; the Academy's recent Best Foreign Language Film nomination was merely the latest bump to its profile. The book looks to be getting a strong push too - it's a 128-page color project, published by Metropolitan Books (of Henry Holt and Company) as both an $18.00 softcover and a $27.50 hardcover. I suspect bookstores will take to it.

Now, I haven't seen any of the movie beyond the trailer, although I've certainly heard plenty. It's actually a documentary project -- albeit heavy on reenactments -- focused on writer/director Ari Folman's inability to recall portions of his service in Israel's 1982 war with Lebanon. Many parties are consulted to help spark something: friends, fellow veterans, a journalist, a psychologist and even a fellow filmmaker. All of them lend opinions or personal stories, which, together, reconstruct a human view of the conflict, culminating in various parties' presence (Folman included) at the Sabra and Shatila massacre of September, 1982, in which Lebanese Phalangist militamen entered a pair of Palestinian refugee camps under the pretext of searching for suspected terrorists in the aftermath of Lebanese president-elect Bashir Gemayel's assassination, and killed hundreds, if not thousands, of refugees.

It's an interesting choice of subject matter for animation, and I don't mean the war story. No, it's the interplay between present-day conversation and dramatized recollection that gets my attention - supposedly there's some contrast between the (allegedly more limited) style of the conversations and the (supposedly fluid, surreal) manner through which the memories are conveyed, which I suspect could come off strikingly in animated form. I've also read that the particular art styles employed give the film a very 'moving comics' feel; I guess it seemed natural to actually make a comic in much the same style, although the prospect gave me pause when I realized that much of what I considered interesting (in theory) about the movie had to do with animation, not graphics.

And unfortunately, I can't say the book proved very effective on its own, though its troubles weren't born from any lack of attention by the film's principals. It's written by writer/director/protagonist Folman himself, with visuals headed by David Polonsky, the film's art director & chief illustrator, working from the original storyboards of animation director Yoni Goodman. Additional art is provided by Asaf & Tomer Hanuka, Michael Faust and Yaara Buchman, all illustrators from the film.

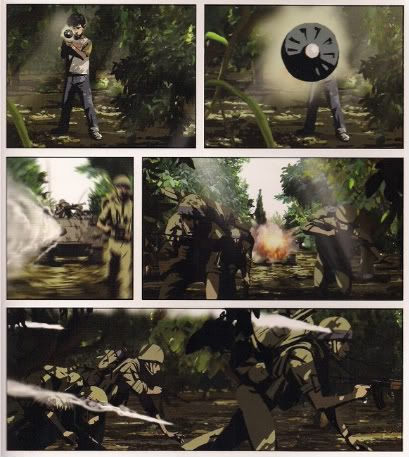

Indeed, from the looks of the Hanukas' production art, it seems some of the comic's images may have been taken virtually as-is from the movie, although I don't think there's any literal screen grabs. Rather, it appears that every effort was made to ensure that the comic resembles the movie as much as possible, without actually transforming it into the most high-falutin' cine-manga ever to grace your local Barnes & Noble.

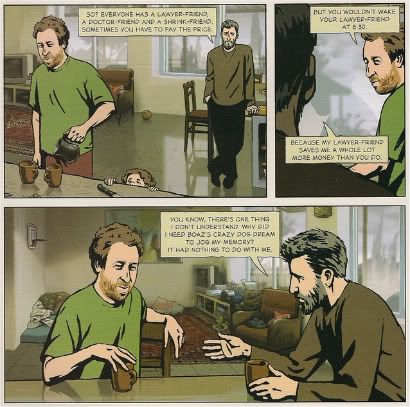

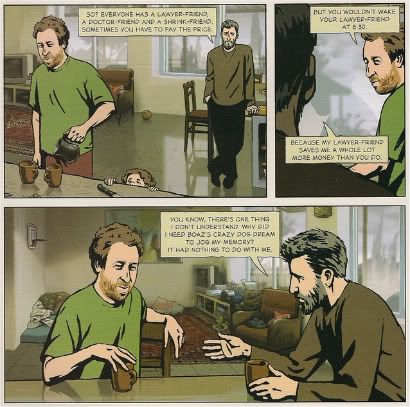

But as well-intentioned as I'm sure it all is, this approach doesn't flatter the comics form. For example, from what I've read, the animation (at least of the non-memory sequences) is executed through the pretty novel method of breaking character images up into many tiny bits, all fit together to form a seamless body, then manipulating various portions at once, puppet-like, to create movement. It does look neat in the movie trailer, but preserving that 'look' in the comic leads to odd effects, like a character having exactly the same facial expression in a series of panels, regardless of what he's saying.

I'm guessing this seems much more natural given the benefit of movement, whereby such limitations could be better integrated into a stylistic whole, but the comics form forces attention on specific gestures and expressions to carry an especial storytelling weight; stripped of the element of movement (and perhaps the vocal inflections of the characters), a small, maybe deliberate limitation suddenly becomes distracting and odd, since different parts of the image are required to perform different duties.

That's a small example, yes, but endemic to the book's approach to the comics form as a vessel for approximating cimetographic effects in a limited manner. It's very much an Official Comics Adaptation in that way, a true supplicant to its cinematic source material, if one prepared to stand and adopt the poise of a literary graphic novel, so very weighty and 21st century lush.

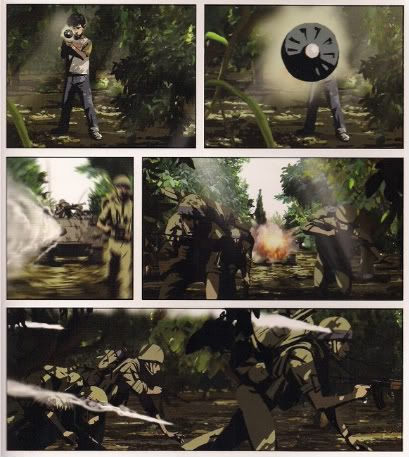

The illustrations themselves are sometimes quite nice, if very digital-oriented and shiny-blurred-flashy; it does the soul good to see a high-profile book come out and make the case for five artists on the same story, each of them unique but guided by clear aesthetic direction, so that variations in style become logical variations in tone. A flashback beach scene might suddenly see the character art cast off all black outlines, to briefly transform young soldiers into more self-evident graphic elements, leaving them both iconic and distanced, as fond recollections might be. A fantasy sequence sees a nude giantess rise from water, all soft features and huge eyes, and light shadows that give her a rich cartoon texture.

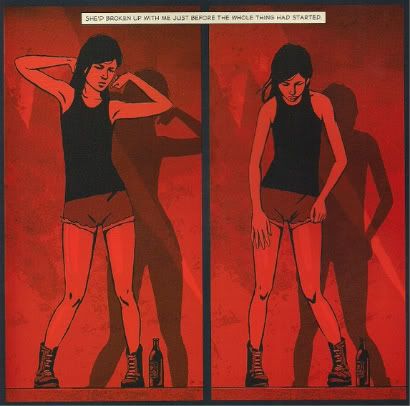

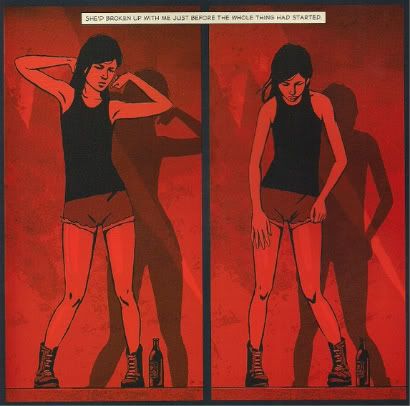

It's a smart mix of approaches, although the variation is strictly illustrative. The book is somewhat less successful at panel-to-panel flow, in that characters frequently seem frozen in place; a side-effect of such struggle to replicate the particulars of storyboards intended to serve as a launch pad for moving pictures, one expects, although I do believe the storyboards were themselves struck from video footage of live actors shot beforehand. Regardless, the final result becomes distracting when characters are called upon to make some particular movement, such as the gun-blazing waltz of the title. It wasn't until I saw the trailer that I could be sure the girl below was supposed to be dancing instead of pouting melodramatically in her narrating ex-boyfriend's face.

I do get the impression that Polonsky may have became aware of this limitation; the storytelling leans firmly on near-omnipresent narration captions used to keep the reader steady as to where characters are, and what they happen to be thinking behind their waxy, dramatically shadowed faces.

Land/cityscape vistas are favored for perspectives, with plenty of long horizontal panels provided for that movie-like 'widescreen' effect - it often seems a bit like The Ultimates, or some other North American pop comic from half a decade ago capering to play at Bruckheimerian bombast, but recontextualized for a 'literary' comic hewing as close to a bona fied cinema source as it possibly can.

Yet Waltz with Bashir has more to lose from that authenticity of origin. If there is some substantive shift in presentational style between the animation's present and recollection, it's certainly not visible here. The illustrations shift in style at times, as indicated above, but memory and conversation are flattened into one experience by the squares and rectangles of page layouts; those many shifts in perspective and scene, steadily narrated and denied much nuance of gesture (which I presume would be remidied by teeming animation), give Folman's storytelling a sensation of abridgement, although plot synopses suggest nearly all of the movie's content is represented.

Some impact remains. The gist of each character's story comes through, some of which are interesting; there's a nice bit with young Folman wandering through an airport terminal that's gradually revealed to be ruined. The work's general thrust remains certain, juxtaposing personal narratives to create a means of approaching a massive tragedy, long ago frozen in notoriety and thus elusive from personal relation, i.e. memory ("Against your will, you were cast in the role of Nazi," muses specialist in longform narrative).

And yes, the movie's big formal flourish is preserved in the comic, as all musing and puzzlement and stories and dreams and artifice are obliterated by a concluding volley of photographic evidence of the atrocity, a reminder that all the subjectivity of filmmaking and interviews and confession can't obscure the plain fact that something happened.

If only the artifice had been more compelling in its sale of subjectivity! I wouldn't call this a bad comic, but I'm also not sure what I'd call it; I feel like I still ought to see the movie to give a thorough opinion on the value of Waltz with Bashir. It's not incomplete so much as outlined in detail, like a very long trailer, or (yeah) a set of storyboards. Or an Official Comics Adaptation. Whether anyone will want that kind of keepsake in this lavish, bookstore-ready form, complete with a premium price tag higher than that of an actual movie ticket -- or, in the hardcover's case, maybe that of the eventual dvd -- remains to be seen.

This should be out very soon. It's the comics version of a high-profile 2008 animated film, the first from Israel to debut in theaters, I think. I'm sure you've heard of it; the Academy's recent Best Foreign Language Film nomination was merely the latest bump to its profile. The book looks to be getting a strong push too - it's a 128-page color project, published by Metropolitan Books (of Henry Holt and Company) as both an $18.00 softcover and a $27.50 hardcover. I suspect bookstores will take to it.

Now, I haven't seen any of the movie beyond the trailer, although I've certainly heard plenty. It's actually a documentary project -- albeit heavy on reenactments -- focused on writer/director Ari Folman's inability to recall portions of his service in Israel's 1982 war with Lebanon. Many parties are consulted to help spark something: friends, fellow veterans, a journalist, a psychologist and even a fellow filmmaker. All of them lend opinions or personal stories, which, together, reconstruct a human view of the conflict, culminating in various parties' presence (Folman included) at the Sabra and Shatila massacre of September, 1982, in which Lebanese Phalangist militamen entered a pair of Palestinian refugee camps under the pretext of searching for suspected terrorists in the aftermath of Lebanese president-elect Bashir Gemayel's assassination, and killed hundreds, if not thousands, of refugees.

It's an interesting choice of subject matter for animation, and I don't mean the war story. No, it's the interplay between present-day conversation and dramatized recollection that gets my attention - supposedly there's some contrast between the (allegedly more limited) style of the conversations and the (supposedly fluid, surreal) manner through which the memories are conveyed, which I suspect could come off strikingly in animated form. I've also read that the particular art styles employed give the film a very 'moving comics' feel; I guess it seemed natural to actually make a comic in much the same style, although the prospect gave me pause when I realized that much of what I considered interesting (in theory) about the movie had to do with animation, not graphics.

And unfortunately, I can't say the book proved very effective on its own, though its troubles weren't born from any lack of attention by the film's principals. It's written by writer/director/protagonist Folman himself, with visuals headed by David Polonsky, the film's art director & chief illustrator, working from the original storyboards of animation director Yoni Goodman. Additional art is provided by Asaf & Tomer Hanuka, Michael Faust and Yaara Buchman, all illustrators from the film.

Indeed, from the looks of the Hanukas' production art, it seems some of the comic's images may have been taken virtually as-is from the movie, although I don't think there's any literal screen grabs. Rather, it appears that every effort was made to ensure that the comic resembles the movie as much as possible, without actually transforming it into the most high-falutin' cine-manga ever to grace your local Barnes & Noble.

But as well-intentioned as I'm sure it all is, this approach doesn't flatter the comics form. For example, from what I've read, the animation (at least of the non-memory sequences) is executed through the pretty novel method of breaking character images up into many tiny bits, all fit together to form a seamless body, then manipulating various portions at once, puppet-like, to create movement. It does look neat in the movie trailer, but preserving that 'look' in the comic leads to odd effects, like a character having exactly the same facial expression in a series of panels, regardless of what he's saying.

I'm guessing this seems much more natural given the benefit of movement, whereby such limitations could be better integrated into a stylistic whole, but the comics form forces attention on specific gestures and expressions to carry an especial storytelling weight; stripped of the element of movement (and perhaps the vocal inflections of the characters), a small, maybe deliberate limitation suddenly becomes distracting and odd, since different parts of the image are required to perform different duties.

That's a small example, yes, but endemic to the book's approach to the comics form as a vessel for approximating cimetographic effects in a limited manner. It's very much an Official Comics Adaptation in that way, a true supplicant to its cinematic source material, if one prepared to stand and adopt the poise of a literary graphic novel, so very weighty and 21st century lush.

The illustrations themselves are sometimes quite nice, if very digital-oriented and shiny-blurred-flashy; it does the soul good to see a high-profile book come out and make the case for five artists on the same story, each of them unique but guided by clear aesthetic direction, so that variations in style become logical variations in tone. A flashback beach scene might suddenly see the character art cast off all black outlines, to briefly transform young soldiers into more self-evident graphic elements, leaving them both iconic and distanced, as fond recollections might be. A fantasy sequence sees a nude giantess rise from water, all soft features and huge eyes, and light shadows that give her a rich cartoon texture.

It's a smart mix of approaches, although the variation is strictly illustrative. The book is somewhat less successful at panel-to-panel flow, in that characters frequently seem frozen in place; a side-effect of such struggle to replicate the particulars of storyboards intended to serve as a launch pad for moving pictures, one expects, although I do believe the storyboards were themselves struck from video footage of live actors shot beforehand. Regardless, the final result becomes distracting when characters are called upon to make some particular movement, such as the gun-blazing waltz of the title. It wasn't until I saw the trailer that I could be sure the girl below was supposed to be dancing instead of pouting melodramatically in her narrating ex-boyfriend's face.

I do get the impression that Polonsky may have became aware of this limitation; the storytelling leans firmly on near-omnipresent narration captions used to keep the reader steady as to where characters are, and what they happen to be thinking behind their waxy, dramatically shadowed faces.

Land/cityscape vistas are favored for perspectives, with plenty of long horizontal panels provided for that movie-like 'widescreen' effect - it often seems a bit like The Ultimates, or some other North American pop comic from half a decade ago capering to play at Bruckheimerian bombast, but recontextualized for a 'literary' comic hewing as close to a bona fied cinema source as it possibly can.

Yet Waltz with Bashir has more to lose from that authenticity of origin. If there is some substantive shift in presentational style between the animation's present and recollection, it's certainly not visible here. The illustrations shift in style at times, as indicated above, but memory and conversation are flattened into one experience by the squares and rectangles of page layouts; those many shifts in perspective and scene, steadily narrated and denied much nuance of gesture (which I presume would be remidied by teeming animation), give Folman's storytelling a sensation of abridgement, although plot synopses suggest nearly all of the movie's content is represented.

Some impact remains. The gist of each character's story comes through, some of which are interesting; there's a nice bit with young Folman wandering through an airport terminal that's gradually revealed to be ruined. The work's general thrust remains certain, juxtaposing personal narratives to create a means of approaching a massive tragedy, long ago frozen in notoriety and thus elusive from personal relation, i.e. memory ("Against your will, you were cast in the role of Nazi," muses specialist in longform narrative).

And yes, the movie's big formal flourish is preserved in the comic, as all musing and puzzlement and stories and dreams and artifice are obliterated by a concluding volley of photographic evidence of the atrocity, a reminder that all the subjectivity of filmmaking and interviews and confession can't obscure the plain fact that something happened.

If only the artifice had been more compelling in its sale of subjectivity! I wouldn't call this a bad comic, but I'm also not sure what I'd call it; I feel like I still ought to see the movie to give a thorough opinion on the value of Waltz with Bashir. It's not incomplete so much as outlined in detail, like a very long trailer, or (yeah) a set of storyboards. Or an Official Comics Adaptation. Whether anyone will want that kind of keepsake in this lavish, bookstore-ready form, complete with a premium price tag higher than that of an actual movie ticket -- or, in the hardcover's case, maybe that of the eventual dvd -- remains to be seen.

<< Home