When Am I?

*Jesus lord, it is crap to work on stuff that can't instantaneously pop up for everyone to see. The next few days ought to bring something new, though.

*Ye Olde '90s Dept: Meanwhile, I've kept on digging through old comics - as if I'd ever stop! There's great rewards sitting around in fifty cent bins across this fine land; strange, forgotten things that carry new significance to our troubled contemporary times. You never know what you'll find.

Like, maybe Brett Lewis and John Paul Leon, creators of The Winter Men, working on a doomed series from 1996 that nobody seems to remember?

Well, ok, I'm stretching a bit. Leon only did covers for this series, and I'm not even 100% sure this is the same Brett Lewis, although it'd be a funny coincidence if someone with the same name was around for a different Image-published series (Bulletproof Monk) less than two years later and went on to collaborate with Leon... whenever the hell The Winter Men actually got started.

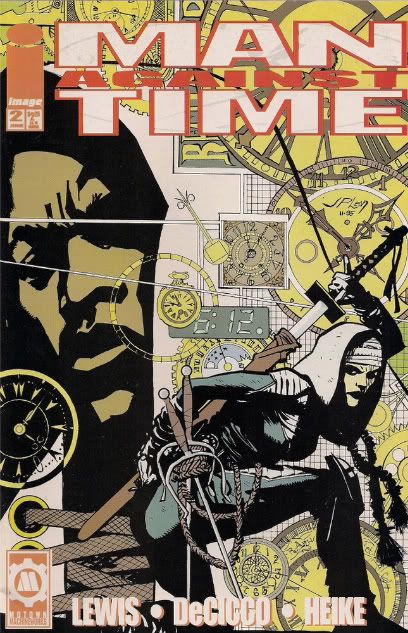

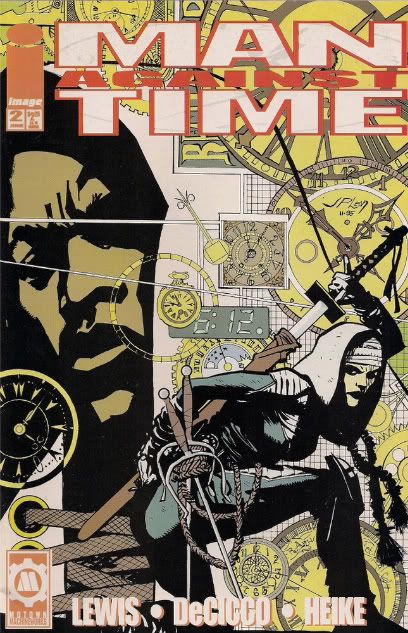

As you can from the cover, Man Against Time (rather than Crime, haw haw) was presented under the banner of Motown Machineworks -- apparently the comics wing of Motown Animation, itself the animation division of the famed Motown Records -- which was headed by Michael Davis (President/CEO) & Denys Cowan (VP/EiC), two of the founders of Milestone Media. "Machineworks" has kind of an omnious ring, like hammers banging on properties as they glide down a conveyor belt toward some hopeful multimedia exploitation, but not a lot came of the line - as far as I can tell, Motown was only ever in the comics game in 1996, which wasn't exactly a banner year for the health of the Direct Market, to say nothing of the unchecked proliferation of readymade superhero universes just then cresting.

But anyway, Motown Machineworks did exist, and Brett Lewis was its editorial director for a short while. Man Against Time appears to be his first-ever published comics work, accompanied by the pencils of one Gino DiCicco, in what seems to be his one and only comics credit. The visuals are very much of the era (and publisher), loaded with splashes and poses and details and muscles, although the energy seems to flag in issue #2 when inker Andrew Pepoy is replaced by Mark Heike and the colorists are changed. Still:

I can't say it's a really good series or a stellar piece of writing or anything - it feels like early work, with a type of throw-everything-at-you aesthetic that suggests a restless creativity without a ton of restraint.

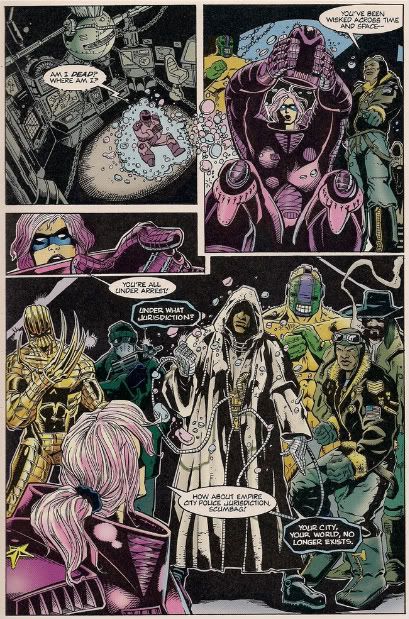

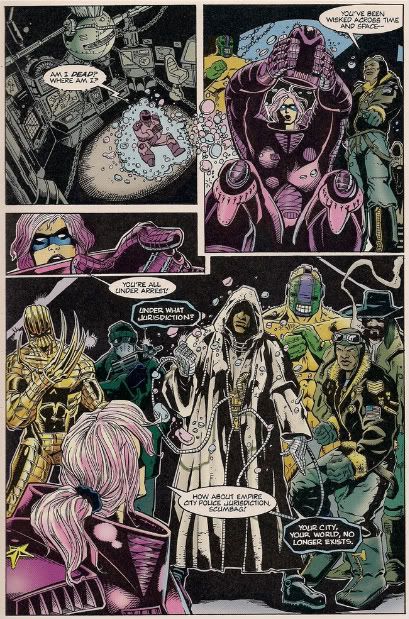

The dialogue is blunt and perpetually declarative, and the pace of the action easily outsteps attempts at characterization - a rocket-suited pink-haired policewoman Of The Future is whisked outside of time and goes from befuddlement in one panel ("You're all under arrest!") to fighting anger half a page later to weeping despair following seven panels and four word balloons of explanation as to why her timeline no longer exists, and that's pretty much the most extensive arc anyone goes through.

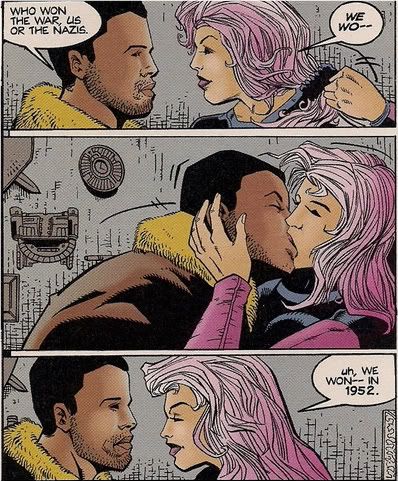

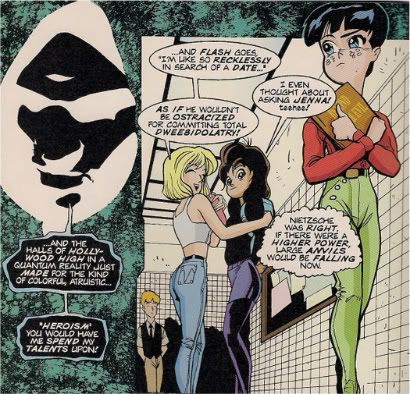

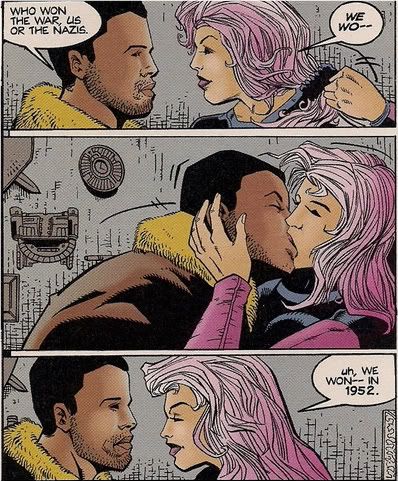

The flow is jerky, with a romantic interlude leading without warning to one of its participants bursting into a different room shouting crucial plot information they've learned off-page, prompting a small explosion of violence by characters otherwise bereft of motivation, or sometimes even names. Maybe it's modernism?

Nah, it strikes me as more the product of a writer with pretty specific ideas of how a series ought to connect -- a lived-in world surrounding the reader and various colorful characters as small mysteries cluster to obscure a grand scheme -- but somehow without the ability (be it through inexperience or interference or something) to pull it off.

Still, it's a fun, loopy plot, while it lasts. The concept of the series has Law, a white-cloaked enigma, plucking people out of their discreet timelines so as apply their special skills to his crack team of extra-temporal operatives; it eventually turns out that Law has actually been creating some of the timelines for the express purpose of cultivating specific skill sets, only to collect the cream of the crop and shut things down on the remaining billions of timeline residents.

So it goes for Tammie, the aforementioned pink-haired cop in a robot suit (chunky and domino-masked in the much-later manner of The Umbrella Academy), chasing Flash Gordon-costumed crooks in the far-flung metropolis of 1985 one moment, then zapped away as Law closes down her universe (without quite telling her) and assigning her to the important task of knocking down trees in the 15th century so as to somehow affect the master future in some obscure way.

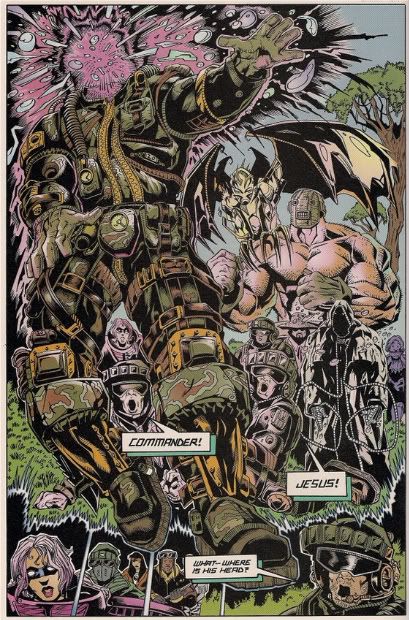

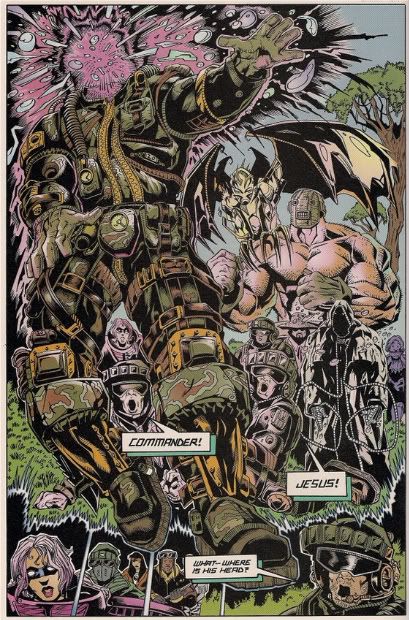

Obscurity is necessary, so as to throw off the Chrono Cops who've been after Law for a while - there may be a psychic and a brute and a gold thing with claws on the team, but our all-powerful anti-hero still needs to step in sometimes and transfer some nosy fucker's head (and only their head) to an alley in 1972. It's little wonder that issue #2 sees Law builds himself a legendary assassin by subtly toying with the emotions of a little girl who's just witnessed her black ops tech father's murder at the hands of ninjas sent by Congress.

Meanwhile, Tammie and a lecherous math whiz named Glom (who closes out his part of the chapter laying on the ground with a bloody face huffing one of Tammie's shoes) infiltrate the funeral luncheon of a character killed in the prior issue, while a 19th century cowboy goes undercover in 18th century Rotterdam County to urge the citizenry to turn on the Redcoats with aid from local natives, who are led by Law to believe that their grandchildren will romp on the land twenty generations hence.

"Why didn't you tell them the truth?" Law is asked by an operative.

"Because I haven't decided it yet."

Of course, trouble was apparent with the series early. As of issue #2, Lewis was no longer listed as Motown Machineworks' editorial director, the position having been replaced(?) with the role of editor, filled by former associate editor Thomas Fassbender. The same page bore a message from production director Jason Medley apologizing to penciller DeCicco for issue #1.

The second issue's house ad for issue #3 listed Lewis as writer, but the actual comic suddenly featured Faust scribe David Quinn on script, working from a story by Lewis and himself - a situation oddly similar to that of later issues of Bulletproof Monk, albeit with no discernible Tim Vigil connection.

It's funny reading issue #3 - the comic all but screeches as Quinn steers the plot in his own direction, at one point dispensing with most of Lewis' supporting cast by having Law get really upset and blast the lot of 'em off to parts unknown in the chronosphere. DeCicco pencils only select pages, with Shawn Martinbrough filling in the rest in his own, completely different style. With issue #4, Milestone veteran ChrisCross took control of the pencils, and Quinn's story became increasingly bizarre, with roughly 1/3 of the issue expended on Law's efforts to prove himself a hero through a manga-style parody of the origin of Spider-Man, while other scenes saw the remaining operatives plot a comedic insurrection.

None of it came to much. An ad for issue #5 popped up in the back, and some websited claim it exists, although I've never seen a copy (or evidence of a copy for sale) myself. The whole Motown Machineworks line seemed to poof out of existence with the summer of 1996, almost as if collected by some weird cloaked time god, determined that none of us would even recognize the stuff left behind.

All right, enough of that. Tons of comics came and went in the immediate post-boom of the mid-'90s, most of 'em rightfully so. Man Against Time is a curiosity, noteworthy for some of the people involved and the lack of information surrounding the whole thing, although far from a satisfying experience.

And yet, I think such things are worthwhile. For their little bits of foreshadowing. Their hints.

There's a bit in issue #2 where the sad little girl has grown up and Law has picked her up for his use, as a means of bookending the issue. She's finished murdering the last of the Congressional ninjas that killed her dad, and she lets out a cry she's been denying herself since Law pursuaded her to keep silent, thus placing her on her life's path. At that moment, she meets her white-cloaked god, and he shows her the massive clockwork machine that allows him to track all timelines, and we see it's not dissimilar to the mechanisms her father used to build weapons, and she realizes that the crucial moment of her childhood has always been connected to that place, that everything she's done since has been timed and planned, like clockwork.

You get the feeling you're standing in the midst of the series' Big Idea, and it's pulled off pretty well, maybe the best bit of the series. It comes to nothing, as did many big ideas of 1996 and surrounding years. Maybe it's more appreciable now, with a stronger Brett Lewis (hopefully the same guy!) around, here at the font of the latest not-quite-a-banner-year for the Direct Market, maybe. The more things change...

*Ye Olde '90s Dept: Meanwhile, I've kept on digging through old comics - as if I'd ever stop! There's great rewards sitting around in fifty cent bins across this fine land; strange, forgotten things that carry new significance to our troubled contemporary times. You never know what you'll find.

Like, maybe Brett Lewis and John Paul Leon, creators of The Winter Men, working on a doomed series from 1996 that nobody seems to remember?

Well, ok, I'm stretching a bit. Leon only did covers for this series, and I'm not even 100% sure this is the same Brett Lewis, although it'd be a funny coincidence if someone with the same name was around for a different Image-published series (Bulletproof Monk) less than two years later and went on to collaborate with Leon... whenever the hell The Winter Men actually got started.

As you can from the cover, Man Against Time (rather than Crime, haw haw) was presented under the banner of Motown Machineworks -- apparently the comics wing of Motown Animation, itself the animation division of the famed Motown Records -- which was headed by Michael Davis (President/CEO) & Denys Cowan (VP/EiC), two of the founders of Milestone Media. "Machineworks" has kind of an omnious ring, like hammers banging on properties as they glide down a conveyor belt toward some hopeful multimedia exploitation, but not a lot came of the line - as far as I can tell, Motown was only ever in the comics game in 1996, which wasn't exactly a banner year for the health of the Direct Market, to say nothing of the unchecked proliferation of readymade superhero universes just then cresting.

But anyway, Motown Machineworks did exist, and Brett Lewis was its editorial director for a short while. Man Against Time appears to be his first-ever published comics work, accompanied by the pencils of one Gino DiCicco, in what seems to be his one and only comics credit. The visuals are very much of the era (and publisher), loaded with splashes and poses and details and muscles, although the energy seems to flag in issue #2 when inker Andrew Pepoy is replaced by Mark Heike and the colorists are changed. Still:

I can't say it's a really good series or a stellar piece of writing or anything - it feels like early work, with a type of throw-everything-at-you aesthetic that suggests a restless creativity without a ton of restraint.

The dialogue is blunt and perpetually declarative, and the pace of the action easily outsteps attempts at characterization - a rocket-suited pink-haired policewoman Of The Future is whisked outside of time and goes from befuddlement in one panel ("You're all under arrest!") to fighting anger half a page later to weeping despair following seven panels and four word balloons of explanation as to why her timeline no longer exists, and that's pretty much the most extensive arc anyone goes through.

The flow is jerky, with a romantic interlude leading without warning to one of its participants bursting into a different room shouting crucial plot information they've learned off-page, prompting a small explosion of violence by characters otherwise bereft of motivation, or sometimes even names. Maybe it's modernism?

Nah, it strikes me as more the product of a writer with pretty specific ideas of how a series ought to connect -- a lived-in world surrounding the reader and various colorful characters as small mysteries cluster to obscure a grand scheme -- but somehow without the ability (be it through inexperience or interference or something) to pull it off.

Still, it's a fun, loopy plot, while it lasts. The concept of the series has Law, a white-cloaked enigma, plucking people out of their discreet timelines so as apply their special skills to his crack team of extra-temporal operatives; it eventually turns out that Law has actually been creating some of the timelines for the express purpose of cultivating specific skill sets, only to collect the cream of the crop and shut things down on the remaining billions of timeline residents.

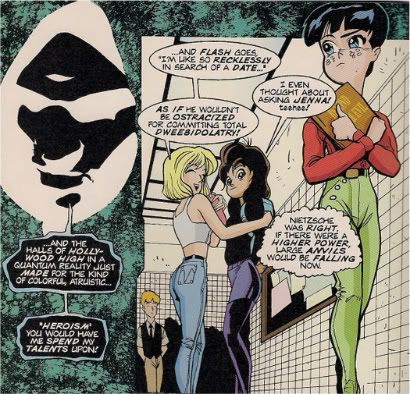

So it goes for Tammie, the aforementioned pink-haired cop in a robot suit (chunky and domino-masked in the much-later manner of The Umbrella Academy), chasing Flash Gordon-costumed crooks in the far-flung metropolis of 1985 one moment, then zapped away as Law closes down her universe (without quite telling her) and assigning her to the important task of knocking down trees in the 15th century so as to somehow affect the master future in some obscure way.

Obscurity is necessary, so as to throw off the Chrono Cops who've been after Law for a while - there may be a psychic and a brute and a gold thing with claws on the team, but our all-powerful anti-hero still needs to step in sometimes and transfer some nosy fucker's head (and only their head) to an alley in 1972. It's little wonder that issue #2 sees Law builds himself a legendary assassin by subtly toying with the emotions of a little girl who's just witnessed her black ops tech father's murder at the hands of ninjas sent by Congress.

Meanwhile, Tammie and a lecherous math whiz named Glom (who closes out his part of the chapter laying on the ground with a bloody face huffing one of Tammie's shoes) infiltrate the funeral luncheon of a character killed in the prior issue, while a 19th century cowboy goes undercover in 18th century Rotterdam County to urge the citizenry to turn on the Redcoats with aid from local natives, who are led by Law to believe that their grandchildren will romp on the land twenty generations hence.

"Why didn't you tell them the truth?" Law is asked by an operative.

"Because I haven't decided it yet."

Of course, trouble was apparent with the series early. As of issue #2, Lewis was no longer listed as Motown Machineworks' editorial director, the position having been replaced(?) with the role of editor, filled by former associate editor Thomas Fassbender. The same page bore a message from production director Jason Medley apologizing to penciller DeCicco for issue #1.

The second issue's house ad for issue #3 listed Lewis as writer, but the actual comic suddenly featured Faust scribe David Quinn on script, working from a story by Lewis and himself - a situation oddly similar to that of later issues of Bulletproof Monk, albeit with no discernible Tim Vigil connection.

It's funny reading issue #3 - the comic all but screeches as Quinn steers the plot in his own direction, at one point dispensing with most of Lewis' supporting cast by having Law get really upset and blast the lot of 'em off to parts unknown in the chronosphere. DeCicco pencils only select pages, with Shawn Martinbrough filling in the rest in his own, completely different style. With issue #4, Milestone veteran ChrisCross took control of the pencils, and Quinn's story became increasingly bizarre, with roughly 1/3 of the issue expended on Law's efforts to prove himself a hero through a manga-style parody of the origin of Spider-Man, while other scenes saw the remaining operatives plot a comedic insurrection.

None of it came to much. An ad for issue #5 popped up in the back, and some websited claim it exists, although I've never seen a copy (or evidence of a copy for sale) myself. The whole Motown Machineworks line seemed to poof out of existence with the summer of 1996, almost as if collected by some weird cloaked time god, determined that none of us would even recognize the stuff left behind.

All right, enough of that. Tons of comics came and went in the immediate post-boom of the mid-'90s, most of 'em rightfully so. Man Against Time is a curiosity, noteworthy for some of the people involved and the lack of information surrounding the whole thing, although far from a satisfying experience.

And yet, I think such things are worthwhile. For their little bits of foreshadowing. Their hints.

There's a bit in issue #2 where the sad little girl has grown up and Law has picked her up for his use, as a means of bookending the issue. She's finished murdering the last of the Congressional ninjas that killed her dad, and she lets out a cry she's been denying herself since Law pursuaded her to keep silent, thus placing her on her life's path. At that moment, she meets her white-cloaked god, and he shows her the massive clockwork machine that allows him to track all timelines, and we see it's not dissimilar to the mechanisms her father used to build weapons, and she realizes that the crucial moment of her childhood has always been connected to that place, that everything she's done since has been timed and planned, like clockwork.

You get the feeling you're standing in the midst of the series' Big Idea, and it's pulled off pretty well, maybe the best bit of the series. It comes to nothing, as did many big ideas of 1996 and surrounding years. Maybe it's more appreciable now, with a stronger Brett Lewis (hopefully the same guy!) around, here at the font of the latest not-quite-a-banner-year for the Direct Market, maybe. The more things change...

<< Home