Return of the Triumph of the Diluted Ambition

The Boys (thus far)

This is writer Garth Ennis' only 'big' series at the moment, now that he's done with The Punisher MAX. It's drawn by Darick Robertson, although he just picked up an inker, Matt Jacobs, in the most recent issue (#22). He also used Rodney Ramos' inks in issue #12, though, so maybe it's just a one-off. Peter Snejbjerg drew a pair of fill-in issues too (#13-14). It all used to be published by Wildstorm, but it got canned under curious circumstances with issue #6; sales were fine -- above the Wildstorm average, really -- but the general tone apparently did not sit well with certain parties over at DC. The project was soon picked up by Dynamite Entertainment - it is anticipated to run the usual-for-Ennis 60 or so issues.

I read a little of this series back when it was new, and I didn't like it much at all. It struck me as a dull retread of capes 'n tights lampoons Ennis had long ago run into the ground, populated by barely-shaded variations on his beloved black ops killers, capable of those very nearly super-human action movie feats that have a way of rendering the writer's oft-voiced dislike for superhero tropes as more a matter of sheer aesthetic discomfort than anything else. Which is fine -- plenty of smart and creative people in the world don't think superhero comics are cool or stylish or attractive at all -- but it's not the type of opposition that easily bears much repetition.

But what do I know? The stuff sells to superhero readers. Why not go and 'out-Preacher Preacher,' a line of Ennis-backed hype that had the queasy effect of boiling his prior long series down to nothing of apparent authorial resonance or value beyond gore and shit jokes and miscellaneous badassery, while assuring readers that sights wouldn't be set an inch higher for the present work, god forbid.

I'm an admirer of a lot of the man's work, though, and I know it's usually a mistake to read interviews or advertisements so seriously. Surely if Ennis was willing to bring a certain level of depth and thematic rigor to the fucking Punisher, it'd probably be best to give him the benefit of the doubt. And, sure enough, The Boys has become a better work than I'd given it credit for back when there was less of it; it's still a flawed thing, yes, but not without virtue, traits that frankly become easier to appreciate the closer you get to the work's surface.

One thing ought to be mentioned quickly - this still isn't much of a satire. It's got the basic parts of one, being the saga of conspiracy-minded Scot (and Simon Pegg lookalike) Wee Hughie, whose beloved (if somewhat new) girlfriend is smooshed to death in the midst of a slam-bang superhuman brawl; Hughie is then recruited by Billy Butcher, a grinning he-man who's putting (back) together an elite team of killer operatives pumped full of super-soldier serum and given the mission of watching over the superhero population, although Butcher clearly has nastier plans in store for those hated, hypocritical, degenerate supes.

And so, four-issue stories abound (save for a two-issue prelude), equipped with elements ranging from little prods at popular superhero tropes (dead heroes often come back, always much dumber than before) to whole adventures devoted to taking on visible superhero interests - the series' third storyline, Get Some, is an extensive shot at Judd Winickish presentations of homosexual characters in superhero comics (particularly evoking Winick's Green Lantern work), which Ennis appears to take as addressing neither the complexities of homosexual relationships nor the deep-seated unease that lives in otherwise well-intentioned heterosexual men.

On the particulars it's a scattered work, with a closeted superhero's sudden desire to fuck anything that does or doesn't move mixing the metaphor a bit too much, and the obligatory homophobe villain spitting out over-the-top slurs that don't strike me as much more convincing than anything in a proper corporate-owned all-ages-or-thereabouts superhero comic. It's also notable that a lot of these works are over half a decade old, coming before works like Ennis' own short run on Wildstorm's The Midnighter.

Yet, while related, the core problem with this series' satirical outlook is more general. Ennis, in 2008, continues to steep his criticism in some secret, shocking superhero dichotomy, that the seeming purity of heroes can (and typically does) mask a capacity for incredible abuse of power. It's a well-taken point, enough so that it should be elementary to literally anyone reading superhero comics today; hell, it's been an active component in straightforward superhero stories since the days of the old genre satires Ennis is so indebted to. One of the first superhero comics I can remember reading is an issue of Spectacular Spider-Man that ended with the Punisher emptying his gun into a supervillain and Spider-Man yelling at him over the intricacies of bringing bigger villains to justice, and Frank Castle just brushing his stupid ass off. Right there's your challenge to the nobility of the superhero idea, in a dead-center genre piece.

Further, even as he raises points long ago belabored, Ennis does little to address the underlying mechanics of the genre. There's a lot of Marshal Law in here, for example, enough so that Ennis seems to be wearing his influences on his sleeve; the acrimony Butcher holds toward Superman/Captain America archetype The Homelander seems a very deliberate reference to the earliest of Pat Mills' and Kevin O'Neill's work -- the titular hero hunter obsessed with the patriotic Public Spirit, he who drove young men into useless wars -- and Ennis quite cleverly revamps the prior work's superhero-as-soldiers motif into superheroes-as-arms, allowing for some riffing on faulty weapons while feeding into the writer's ever-present passion for military accoutrement.

But Mills' writing was more passionate in its critique, and willing to swiftly acknowledge that its anti-hero's maverick style could (perhaps inevitably) be co-opted as a fresh brand for the superhero status quo, with little of substance truly changed; Ennis, in contrast, has thus far been content to stretch the suspense of Butcher's obsession running into Hughie's compassion over the course of the series, elementary as the point might be. Even in later, less effective storylines, Mills adopted a jaundiced view toward the very concept of 'heroism,' always exposing heroic figures as latently awful or ineffective, and constantly returning his title character to his violent, angry, primal state.

Ennis' work, meanwhile, often seems upset that heroes can't really exist, with a bit of hope held out that maybe the superhero dream can yet be fulfilled in a more idealistic manner, via the few 'good' super-powered characters presented. It's probably a bit closer to Rick Veitch's outlook, his incomplete King Hell Heroica being another apparent influence (at one point Butcher tells the story of a woman being killed by a super-powered, heat-vision capable infant, an extremely similar scenario to the most memorable bit of The Maximortal) - but Veitch's work also had the force of historical anger behind it, a rage at the debased state of superheroes (no special revelation to him - Brat Pack presumed the reader knew that supes could and would take us to hell) manifesting as one more blob of spit being slung at writers and artists long ago sucked dry by the corporate machine.

Compared to all of that, The Boys just isn't very insightful as commentary; it's hard to be shocked out of genre torpor by Justice League stand-ins demanding blowjobs when Epic Comics introduced thousands of minds to the concept of waterboarding via a Punisher/Avengers burlesque in 1989.

Still, there's something to this series. Looking at it another way, it's more realistic that some superheroes would actually be as good as advertised, just as some black-clad killer motherfuckers would long for kinder relations (especially if they're the reader/Simon Pegg surrogate). And while I've never quite been sold on Ennis' satire, he's proven himself to be very adept at worldbuilding, and carefully thinking through the implications of what goes on in his environments.

That's the trick, I think. By not looking at The Boys as anything 'about' superheroes -- which can be sticky, since parts of it seem deliberately tuned toward that reading -- but instead as a bleakly funny drama set among superheroes and superpowered anti-heroes, it becomes exponentially more effective.

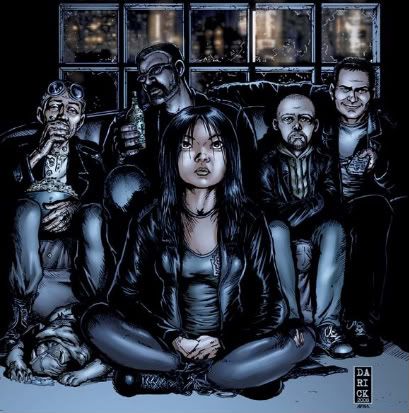

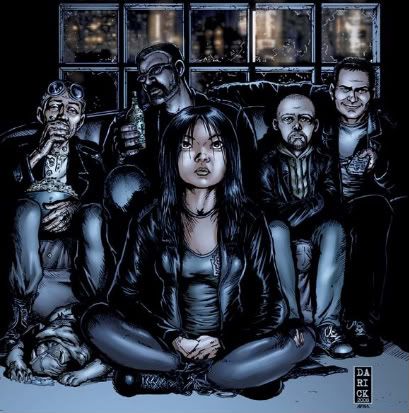

It's still not without its faults, sure. Some of the plotting seems strung together mainly as a means of getting along with striking/funny images - the Russia-set Glorious Five Year Plan is especially haphazard in this regard. A few of the nominal primary characters still haven't taken more than a few steps of development away from their introductions, although Robertson at least lends a certain alien quality to the series' take on the Deadly Lil' Lady character type, laying down to sleep on tables when she's bored, or generally lounging in a catatonic state without violence to prompt her.

The visuals as a whole have gotten steadily more effective; I tend to find Robertson's visuals to be less interesting the more slickly 'realistic' he gets, and I'm not huge on 'casting' actors in comics, retroactively okayed or not (and yes, I know the history of the practice). But his Simon Pegg has gradually become a little less detailed, more self-sufficiently Wee Hughie, as the world surrounding him has grown harsher and inkier. I suspect part of this might be due to the workload of balancing a monthly book with everything else - some of it starts to resemble Robertson's issues of 52, all harsh and dark.

But I like that here. I think a 'messier,' more darkly cartooned style fits The Boys well, transforming Robertson's able superhero compostions into something good and dirty, like nasty violence is ready to spring out of anything, with nobody capable of escaping the world's hard nature - Jacobs' scratchy inks on issue #22 teased out even more of this feeling, and it compliments Ennis' storytelling nicely.

And that storytelling, as it exists within Ennis' world, can be interesting. Issue by issue, the series builds up an impressive air of decadence, a hard-R place in which perversion is most folks' default, and 'realism' has a way of creeping up in the worst ways. The most recent storyline, I Tell You No Lie, G.I., has mostly been taken up by a history lesson from a superhero image-maker (i.e. comic book writer) called the Legend, who's grown more unreal and trollish with every issue Robertson has drawn (to good effect!); it was a nice, thought-through infodump, but it paused in issue #21 for a rip-down-the-sky 9/11 adventure that illustrated a lot of things that could go wrong with attempting to stop a soaring aircraft with various JLA orthodox superpowers (that's the Aquaman character above center, trying to help).

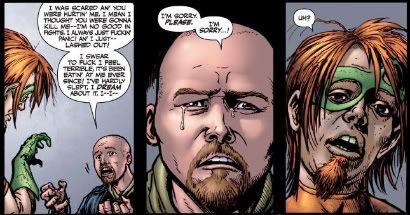

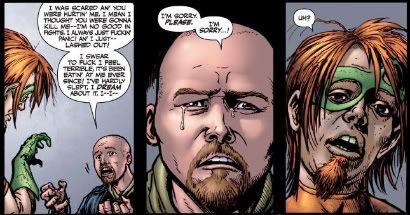

Beyond all that, Ennis' control of the character relationships is very measured, very effective. Butcher's and Hughie's interactions may be typical of the writer -- the sensitive fellow with a killer's heart and the hard man lost in darkness -- but there's a careful rapport that keeps either from seeming stale. And while clueless Hughie's relationship with a nice woman who's secretly (*gasp* *choke*) a superheroine might lend itself to some familiar melodrama and/or a too-cute take on secret identities, there's a genuine warmth to Ennis' scripting that enlivens his ever-careful pacing.

It can be a fun comic, this. Depressing too, considering the wall of corruption Ennis builds around his superheroes and superhumans. It's well-told and smartly detailed, enough so that you find yourself pulled down to the level of Ennis' superhuman world, where cracks seen from farther up aren't so important. Is it a victory for superficiality? I don't think so - it's just that Ennis' talents support different levels of engagement with the work, some of which are simply more pleasing than others. I'm not where I started, but I'm glad to be standing where I am.

This is writer Garth Ennis' only 'big' series at the moment, now that he's done with The Punisher MAX. It's drawn by Darick Robertson, although he just picked up an inker, Matt Jacobs, in the most recent issue (#22). He also used Rodney Ramos' inks in issue #12, though, so maybe it's just a one-off. Peter Snejbjerg drew a pair of fill-in issues too (#13-14). It all used to be published by Wildstorm, but it got canned under curious circumstances with issue #6; sales were fine -- above the Wildstorm average, really -- but the general tone apparently did not sit well with certain parties over at DC. The project was soon picked up by Dynamite Entertainment - it is anticipated to run the usual-for-Ennis 60 or so issues.

I read a little of this series back when it was new, and I didn't like it much at all. It struck me as a dull retread of capes 'n tights lampoons Ennis had long ago run into the ground, populated by barely-shaded variations on his beloved black ops killers, capable of those very nearly super-human action movie feats that have a way of rendering the writer's oft-voiced dislike for superhero tropes as more a matter of sheer aesthetic discomfort than anything else. Which is fine -- plenty of smart and creative people in the world don't think superhero comics are cool or stylish or attractive at all -- but it's not the type of opposition that easily bears much repetition.

But what do I know? The stuff sells to superhero readers. Why not go and 'out-Preacher Preacher,' a line of Ennis-backed hype that had the queasy effect of boiling his prior long series down to nothing of apparent authorial resonance or value beyond gore and shit jokes and miscellaneous badassery, while assuring readers that sights wouldn't be set an inch higher for the present work, god forbid.

I'm an admirer of a lot of the man's work, though, and I know it's usually a mistake to read interviews or advertisements so seriously. Surely if Ennis was willing to bring a certain level of depth and thematic rigor to the fucking Punisher, it'd probably be best to give him the benefit of the doubt. And, sure enough, The Boys has become a better work than I'd given it credit for back when there was less of it; it's still a flawed thing, yes, but not without virtue, traits that frankly become easier to appreciate the closer you get to the work's surface.

One thing ought to be mentioned quickly - this still isn't much of a satire. It's got the basic parts of one, being the saga of conspiracy-minded Scot (and Simon Pegg lookalike) Wee Hughie, whose beloved (if somewhat new) girlfriend is smooshed to death in the midst of a slam-bang superhuman brawl; Hughie is then recruited by Billy Butcher, a grinning he-man who's putting (back) together an elite team of killer operatives pumped full of super-soldier serum and given the mission of watching over the superhero population, although Butcher clearly has nastier plans in store for those hated, hypocritical, degenerate supes.

And so, four-issue stories abound (save for a two-issue prelude), equipped with elements ranging from little prods at popular superhero tropes (dead heroes often come back, always much dumber than before) to whole adventures devoted to taking on visible superhero interests - the series' third storyline, Get Some, is an extensive shot at Judd Winickish presentations of homosexual characters in superhero comics (particularly evoking Winick's Green Lantern work), which Ennis appears to take as addressing neither the complexities of homosexual relationships nor the deep-seated unease that lives in otherwise well-intentioned heterosexual men.

On the particulars it's a scattered work, with a closeted superhero's sudden desire to fuck anything that does or doesn't move mixing the metaphor a bit too much, and the obligatory homophobe villain spitting out over-the-top slurs that don't strike me as much more convincing than anything in a proper corporate-owned all-ages-or-thereabouts superhero comic. It's also notable that a lot of these works are over half a decade old, coming before works like Ennis' own short run on Wildstorm's The Midnighter.

Yet, while related, the core problem with this series' satirical outlook is more general. Ennis, in 2008, continues to steep his criticism in some secret, shocking superhero dichotomy, that the seeming purity of heroes can (and typically does) mask a capacity for incredible abuse of power. It's a well-taken point, enough so that it should be elementary to literally anyone reading superhero comics today; hell, it's been an active component in straightforward superhero stories since the days of the old genre satires Ennis is so indebted to. One of the first superhero comics I can remember reading is an issue of Spectacular Spider-Man that ended with the Punisher emptying his gun into a supervillain and Spider-Man yelling at him over the intricacies of bringing bigger villains to justice, and Frank Castle just brushing his stupid ass off. Right there's your challenge to the nobility of the superhero idea, in a dead-center genre piece.

Further, even as he raises points long ago belabored, Ennis does little to address the underlying mechanics of the genre. There's a lot of Marshal Law in here, for example, enough so that Ennis seems to be wearing his influences on his sleeve; the acrimony Butcher holds toward Superman/Captain America archetype The Homelander seems a very deliberate reference to the earliest of Pat Mills' and Kevin O'Neill's work -- the titular hero hunter obsessed with the patriotic Public Spirit, he who drove young men into useless wars -- and Ennis quite cleverly revamps the prior work's superhero-as-soldiers motif into superheroes-as-arms, allowing for some riffing on faulty weapons while feeding into the writer's ever-present passion for military accoutrement.

But Mills' writing was more passionate in its critique, and willing to swiftly acknowledge that its anti-hero's maverick style could (perhaps inevitably) be co-opted as a fresh brand for the superhero status quo, with little of substance truly changed; Ennis, in contrast, has thus far been content to stretch the suspense of Butcher's obsession running into Hughie's compassion over the course of the series, elementary as the point might be. Even in later, less effective storylines, Mills adopted a jaundiced view toward the very concept of 'heroism,' always exposing heroic figures as latently awful or ineffective, and constantly returning his title character to his violent, angry, primal state.

Ennis' work, meanwhile, often seems upset that heroes can't really exist, with a bit of hope held out that maybe the superhero dream can yet be fulfilled in a more idealistic manner, via the few 'good' super-powered characters presented. It's probably a bit closer to Rick Veitch's outlook, his incomplete King Hell Heroica being another apparent influence (at one point Butcher tells the story of a woman being killed by a super-powered, heat-vision capable infant, an extremely similar scenario to the most memorable bit of The Maximortal) - but Veitch's work also had the force of historical anger behind it, a rage at the debased state of superheroes (no special revelation to him - Brat Pack presumed the reader knew that supes could and would take us to hell) manifesting as one more blob of spit being slung at writers and artists long ago sucked dry by the corporate machine.

Compared to all of that, The Boys just isn't very insightful as commentary; it's hard to be shocked out of genre torpor by Justice League stand-ins demanding blowjobs when Epic Comics introduced thousands of minds to the concept of waterboarding via a Punisher/Avengers burlesque in 1989.

Still, there's something to this series. Looking at it another way, it's more realistic that some superheroes would actually be as good as advertised, just as some black-clad killer motherfuckers would long for kinder relations (especially if they're the reader/Simon Pegg surrogate). And while I've never quite been sold on Ennis' satire, he's proven himself to be very adept at worldbuilding, and carefully thinking through the implications of what goes on in his environments.

That's the trick, I think. By not looking at The Boys as anything 'about' superheroes -- which can be sticky, since parts of it seem deliberately tuned toward that reading -- but instead as a bleakly funny drama set among superheroes and superpowered anti-heroes, it becomes exponentially more effective.

It's still not without its faults, sure. Some of the plotting seems strung together mainly as a means of getting along with striking/funny images - the Russia-set Glorious Five Year Plan is especially haphazard in this regard. A few of the nominal primary characters still haven't taken more than a few steps of development away from their introductions, although Robertson at least lends a certain alien quality to the series' take on the Deadly Lil' Lady character type, laying down to sleep on tables when she's bored, or generally lounging in a catatonic state without violence to prompt her.

The visuals as a whole have gotten steadily more effective; I tend to find Robertson's visuals to be less interesting the more slickly 'realistic' he gets, and I'm not huge on 'casting' actors in comics, retroactively okayed or not (and yes, I know the history of the practice). But his Simon Pegg has gradually become a little less detailed, more self-sufficiently Wee Hughie, as the world surrounding him has grown harsher and inkier. I suspect part of this might be due to the workload of balancing a monthly book with everything else - some of it starts to resemble Robertson's issues of 52, all harsh and dark.

But I like that here. I think a 'messier,' more darkly cartooned style fits The Boys well, transforming Robertson's able superhero compostions into something good and dirty, like nasty violence is ready to spring out of anything, with nobody capable of escaping the world's hard nature - Jacobs' scratchy inks on issue #22 teased out even more of this feeling, and it compliments Ennis' storytelling nicely.

And that storytelling, as it exists within Ennis' world, can be interesting. Issue by issue, the series builds up an impressive air of decadence, a hard-R place in which perversion is most folks' default, and 'realism' has a way of creeping up in the worst ways. The most recent storyline, I Tell You No Lie, G.I., has mostly been taken up by a history lesson from a superhero image-maker (i.e. comic book writer) called the Legend, who's grown more unreal and trollish with every issue Robertson has drawn (to good effect!); it was a nice, thought-through infodump, but it paused in issue #21 for a rip-down-the-sky 9/11 adventure that illustrated a lot of things that could go wrong with attempting to stop a soaring aircraft with various JLA orthodox superpowers (that's the Aquaman character above center, trying to help).

Beyond all that, Ennis' control of the character relationships is very measured, very effective. Butcher's and Hughie's interactions may be typical of the writer -- the sensitive fellow with a killer's heart and the hard man lost in darkness -- but there's a careful rapport that keeps either from seeming stale. And while clueless Hughie's relationship with a nice woman who's secretly (*gasp* *choke*) a superheroine might lend itself to some familiar melodrama and/or a too-cute take on secret identities, there's a genuine warmth to Ennis' scripting that enlivens his ever-careful pacing.

It can be a fun comic, this. Depressing too, considering the wall of corruption Ennis builds around his superheroes and superhumans. It's well-told and smartly detailed, enough so that you find yourself pulled down to the level of Ennis' superhuman world, where cracks seen from farther up aren't so important. Is it a victory for superficiality? I don't think so - it's just that Ennis' talents support different levels of engagement with the work, some of which are simply more pleasing than others. I'm not where I started, but I'm glad to be standing where I am.

<< Home