Another Walking Man

A Distant Neighborhood Vol. 1 (of 2)

This is a new Jirô Taniguchi translation from the redoubtable Fanfare/Ponent Mon. It'll be $23.00 for 200 b&w pages upon North American distribution, whenever that is; a small number of early copies apparently slipped out at San Diego, but that appears to be the extent of the release so far.

You're likely to hear more when copies start getting out, if only by virtue of the thing's reputation. Originally hailing from the pages of the venerable seinen magazine Big Comic in 1998, A Distant Neighborhood has since become one of Taniguchi's most praised works, having won an Excellence Prize for Manga at the 1999 Japan Media Arts Festival and the Prize for Scenario at the 2003 Angoulême International Comics Festival. Indeed, the work's renown in Europe is enough that a feature film adaptation by Belgian director Sam Garbarski is currently underway, titled Quartier lointain, after the French translation, with the locale moved to Paris.

And twitchy as that may leave you, seeing an acclaimed Japanese work plunked down into a European setting for cinema airing, it's nonetheless worth noting that Taniguchi has always seemed an especially cosmopolitan mangaka, coming of artistic age in the early '70s at roughly the same time as Akira artist Katsuhiro Otomo; both men flaunt a distinctly western influence in their heavy pages, tight with realistic detail and populated by de-stylized (if still very much cartooned) characters. In later years Taniguchi's French connection would become personalized, as he began to work in collaboration with the likes of Frédéric Boilet (Tokyo Is My Garden, 1997) and Moebius (Icaro, 2000); Boilet, in fact, personally reoriented the present volume's art to a left-to-right reading format, with Taniguchi's consent.

Yet you just can't take the manga out of the man, and I suspect you remove the Japanese from the work at your peril. I'm not just talking about the book's autobiographical elements, although that's certainly pertinent: the protagonist, Hiroshi, is roughly Taniguchi's age as of 1998, and most of the story takes place in Kurayoshi, of the low-population Tottori Prefecture where the artist grew up. And then Hiroshi, by some mysterious means, finds his adult mind warped back in time to control his 14-year old body in 1963, the year his father abandoned his family with no explanation, and Taniguchi too was the age of that father, and his father when he was a kid for real.

But no, I'm really talking about the utterly straightforward manner in which the story plays out, calm with storytelling clarity and poetic insofar as one panel logically follows the next to present another clean, perhaps lovely scene. This is the disposition I pick up from a lot of slice-of-life, non-'genre' mainstream manga, and Taniguchi's realism quiets it even further. It's a story-driven work, this -- one of the main visual metaphors is helpfully explained via narration, in case you were feeling lost -- yet it's still awfully close in tone to The Walking Man, the artist's 1992 saunter through various unadorned locales, your vision as if his.

Frankly, I prefer some of Taniguchi's collaborations over these solo works, at least from what's available in English; his books with writer Natsuo Sekikawa benefit greatly from the restlessness of their writer, coaxing out the cool pathos of the heavily visual Hotel Harbour View or matching the verisimilitude of the vivid period settings of The Times of Botchan with a demanding density of text rarely seen in the 'literary' manga seen around here. In contrast, Taniguchi alone tends toward an on-the-nose directness in his stories that allows for some lovely visuals but a niggling superficiality in the way his words and pictures interact; it's little surprise that the most hailed of Fanfare's releases in North America, the Walking Man, is by far the book with the least to translate.

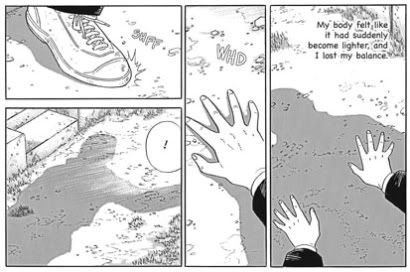

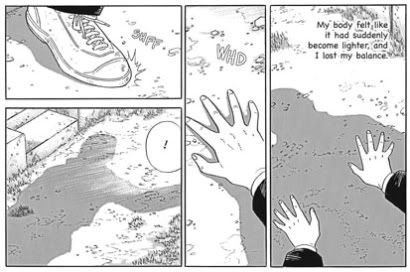

So it goes with this one too, its writing prize at Angoulême notwithstanding. Hiroshi is almost always explaining things; it's not enough for him to just sit up in his teenage bed, alarmed - he has to muse "Have I... still not woken from this dream?!" after which we get two panels of 1963 in action, subsequently punctuated with "Oh no... nothing's changed!"

Sometimes he fills us in on what he knows about his peers as an adult, the adult's narration acting as counterpoint to the child's visuals, but other times he merely announces his state of mind, as if to close off any possible reader confusion when confronted with a new scene; the exception is the book's early swoon over the old city as Hiroshi first beholds it, where a little ambiguity might be appropriate, for a moment, before its disposed of pages later. Occasionally he even briefly reiterates the book's premise, maybe for the benefit of folks joining the serial late; at least he's got a fantastical enough premise at hand that repeating things doesn't seem all that odd.

Mostly, however, Hiroshi comes to tell us of sensations, as if to vivify Taniguchi's immaculately composed gazes at period scenery. This kid gets to enjoy his youth, running faster from knowing the burden of age and acing his classes with proven adult skills, enough so that an otherwise unapproachable girl takes notice. There's some trouble too: we gradually learn that Hiroshi is either an alcoholic or well on the way, and the absence of his physical dependency doesn't necessarily abrogate his psychological needs. Still, he remains compelled to right the wrongs of the past, striding beneath Taniguchi's frequent visual motif, the mighty sky, constant in contempt of human time.

"Perhaps eternity is what the sky represents," narrates Hiroshi. Of course.

Don't let me give you the impression that the book is without charm, though. The draftsmanship is impeccable, naturally, and some of the situations are pretty funny - there's a good bit with Hiroshi inadvertently wowing the campus tough guys with his desire to smoke a real old-timey heavy-duty cigarette, and a decent running gag concerning Our Man's tendency to spill some of the beans regarding his odd situation to various people, none of whom understand at all.

It's also probably liable to go down as the most polite comic of 2009, rarely less than generous toward the people of decades gone by, even when the adult men are prone to giving an out-of-social-bounds Hiroshi a period-appropriate smack. The boy observes his kid sister in bed, frowning slightly, wisfully recounting how her young dreams will fade, and how her happiness will be in domesticity. A date with the aforementioned popular girl mostly gives the man in Hiroshi a chance to beam over how sweet she is as a girl as he gently prods her to pursue the goals he knows she'll realize. It's telling that the most searing bit of drama comes when Hiroshi envisions what's happening back in the present, where his wife and daughters are -- *gasp* -- speaking disrespectfully of him in his absence!

There's some utility to that, sure: it's how we find out Hiroshi maybe isn't as stellar an adult as he is a second-chance kid, possibly-maybe due to his own soon-to-vanish dad. But its effect, its tragedy in a man realizing his family is hiding things, talking about him - it's the anxiety of a middle-aged man, eased into the '90s status quo, his main problem being he doesn't fit the societal status quo as well as he could, as a family man, as a husband and father.

Indeed, what sets this story apart from similar takes -- Alex Robinson's 2008 Too Cool to Be Forgotten is notably similar, mixing the time warp premise with a physical vice (smoking, not drinking) and the looming father issues -- is the maturity, the age in its telling, the dominant tone of reflection and troubled nostalgia by a middle-aged man, for men of the same age, probably successful in some way, fine with society, but maybe thinking about their own fathers and their family situation, and the trials of their parents, the youth of World War II, in light of their own path as adults and, implicitly, the path of their nation. I wrote about a Howard Chaykin comic the other day, and I mentioned that Japan seems like the only country with a lot of comics aimed squarely at older men; this is clearly one of them.

And that might also account for the work's aesthetic, its sometimes blunt, clumsy rush toward explication. It is not a North American comic, nor a European album, it is Japanese, and thus part of the manga tradition, where comics grew and grew as mass entertainment, spreading to mature with the readership. I wonder if there wasn't much need to 'prove' comics to readers, to become as intense and arty as 'literary' or 'markmaking' resistance, to flaunt the elements of the form like Asterios Polyp does, to exist as 'art' in the twilight of an outmoded pamphlet format; there was Garo, and there is Ax, but I've always been told there aren't many more art comics in Japan than in the United States, regardless of how much more manga there is.

Instead, there's fat pamphlets for mature readers like Big Comic, with stories often as direct as can be, from the ease of an accomplished popular medium. This could be a culture clash, my reservations. It brings to mind a question a reader asked of Grant Morrison during a spotlight panel at the New York Comic Con the other year. The guy didn't think he understood the last (first) issue of The Invisibles.

"Of course you understood it," Morrison replied, "the words were what you read, and the pictures were what you saw."

You can bank on that here, morso than usual, for better or worse.

This is a new Jirô Taniguchi translation from the redoubtable Fanfare/Ponent Mon. It'll be $23.00 for 200 b&w pages upon North American distribution, whenever that is; a small number of early copies apparently slipped out at San Diego, but that appears to be the extent of the release so far.

You're likely to hear more when copies start getting out, if only by virtue of the thing's reputation. Originally hailing from the pages of the venerable seinen magazine Big Comic in 1998, A Distant Neighborhood has since become one of Taniguchi's most praised works, having won an Excellence Prize for Manga at the 1999 Japan Media Arts Festival and the Prize for Scenario at the 2003 Angoulême International Comics Festival. Indeed, the work's renown in Europe is enough that a feature film adaptation by Belgian director Sam Garbarski is currently underway, titled Quartier lointain, after the French translation, with the locale moved to Paris.

And twitchy as that may leave you, seeing an acclaimed Japanese work plunked down into a European setting for cinema airing, it's nonetheless worth noting that Taniguchi has always seemed an especially cosmopolitan mangaka, coming of artistic age in the early '70s at roughly the same time as Akira artist Katsuhiro Otomo; both men flaunt a distinctly western influence in their heavy pages, tight with realistic detail and populated by de-stylized (if still very much cartooned) characters. In later years Taniguchi's French connection would become personalized, as he began to work in collaboration with the likes of Frédéric Boilet (Tokyo Is My Garden, 1997) and Moebius (Icaro, 2000); Boilet, in fact, personally reoriented the present volume's art to a left-to-right reading format, with Taniguchi's consent.

Yet you just can't take the manga out of the man, and I suspect you remove the Japanese from the work at your peril. I'm not just talking about the book's autobiographical elements, although that's certainly pertinent: the protagonist, Hiroshi, is roughly Taniguchi's age as of 1998, and most of the story takes place in Kurayoshi, of the low-population Tottori Prefecture where the artist grew up. And then Hiroshi, by some mysterious means, finds his adult mind warped back in time to control his 14-year old body in 1963, the year his father abandoned his family with no explanation, and Taniguchi too was the age of that father, and his father when he was a kid for real.

But no, I'm really talking about the utterly straightforward manner in which the story plays out, calm with storytelling clarity and poetic insofar as one panel logically follows the next to present another clean, perhaps lovely scene. This is the disposition I pick up from a lot of slice-of-life, non-'genre' mainstream manga, and Taniguchi's realism quiets it even further. It's a story-driven work, this -- one of the main visual metaphors is helpfully explained via narration, in case you were feeling lost -- yet it's still awfully close in tone to The Walking Man, the artist's 1992 saunter through various unadorned locales, your vision as if his.

Frankly, I prefer some of Taniguchi's collaborations over these solo works, at least from what's available in English; his books with writer Natsuo Sekikawa benefit greatly from the restlessness of their writer, coaxing out the cool pathos of the heavily visual Hotel Harbour View or matching the verisimilitude of the vivid period settings of The Times of Botchan with a demanding density of text rarely seen in the 'literary' manga seen around here. In contrast, Taniguchi alone tends toward an on-the-nose directness in his stories that allows for some lovely visuals but a niggling superficiality in the way his words and pictures interact; it's little surprise that the most hailed of Fanfare's releases in North America, the Walking Man, is by far the book with the least to translate.

So it goes with this one too, its writing prize at Angoulême notwithstanding. Hiroshi is almost always explaining things; it's not enough for him to just sit up in his teenage bed, alarmed - he has to muse "Have I... still not woken from this dream?!" after which we get two panels of 1963 in action, subsequently punctuated with "Oh no... nothing's changed!"

Sometimes he fills us in on what he knows about his peers as an adult, the adult's narration acting as counterpoint to the child's visuals, but other times he merely announces his state of mind, as if to close off any possible reader confusion when confronted with a new scene; the exception is the book's early swoon over the old city as Hiroshi first beholds it, where a little ambiguity might be appropriate, for a moment, before its disposed of pages later. Occasionally he even briefly reiterates the book's premise, maybe for the benefit of folks joining the serial late; at least he's got a fantastical enough premise at hand that repeating things doesn't seem all that odd.

Mostly, however, Hiroshi comes to tell us of sensations, as if to vivify Taniguchi's immaculately composed gazes at period scenery. This kid gets to enjoy his youth, running faster from knowing the burden of age and acing his classes with proven adult skills, enough so that an otherwise unapproachable girl takes notice. There's some trouble too: we gradually learn that Hiroshi is either an alcoholic or well on the way, and the absence of his physical dependency doesn't necessarily abrogate his psychological needs. Still, he remains compelled to right the wrongs of the past, striding beneath Taniguchi's frequent visual motif, the mighty sky, constant in contempt of human time.

"Perhaps eternity is what the sky represents," narrates Hiroshi. Of course.

Don't let me give you the impression that the book is without charm, though. The draftsmanship is impeccable, naturally, and some of the situations are pretty funny - there's a good bit with Hiroshi inadvertently wowing the campus tough guys with his desire to smoke a real old-timey heavy-duty cigarette, and a decent running gag concerning Our Man's tendency to spill some of the beans regarding his odd situation to various people, none of whom understand at all.

It's also probably liable to go down as the most polite comic of 2009, rarely less than generous toward the people of decades gone by, even when the adult men are prone to giving an out-of-social-bounds Hiroshi a period-appropriate smack. The boy observes his kid sister in bed, frowning slightly, wisfully recounting how her young dreams will fade, and how her happiness will be in domesticity. A date with the aforementioned popular girl mostly gives the man in Hiroshi a chance to beam over how sweet she is as a girl as he gently prods her to pursue the goals he knows she'll realize. It's telling that the most searing bit of drama comes when Hiroshi envisions what's happening back in the present, where his wife and daughters are -- *gasp* -- speaking disrespectfully of him in his absence!

There's some utility to that, sure: it's how we find out Hiroshi maybe isn't as stellar an adult as he is a second-chance kid, possibly-maybe due to his own soon-to-vanish dad. But its effect, its tragedy in a man realizing his family is hiding things, talking about him - it's the anxiety of a middle-aged man, eased into the '90s status quo, his main problem being he doesn't fit the societal status quo as well as he could, as a family man, as a husband and father.

Indeed, what sets this story apart from similar takes -- Alex Robinson's 2008 Too Cool to Be Forgotten is notably similar, mixing the time warp premise with a physical vice (smoking, not drinking) and the looming father issues -- is the maturity, the age in its telling, the dominant tone of reflection and troubled nostalgia by a middle-aged man, for men of the same age, probably successful in some way, fine with society, but maybe thinking about their own fathers and their family situation, and the trials of their parents, the youth of World War II, in light of their own path as adults and, implicitly, the path of their nation. I wrote about a Howard Chaykin comic the other day, and I mentioned that Japan seems like the only country with a lot of comics aimed squarely at older men; this is clearly one of them.

And that might also account for the work's aesthetic, its sometimes blunt, clumsy rush toward explication. It is not a North American comic, nor a European album, it is Japanese, and thus part of the manga tradition, where comics grew and grew as mass entertainment, spreading to mature with the readership. I wonder if there wasn't much need to 'prove' comics to readers, to become as intense and arty as 'literary' or 'markmaking' resistance, to flaunt the elements of the form like Asterios Polyp does, to exist as 'art' in the twilight of an outmoded pamphlet format; there was Garo, and there is Ax, but I've always been told there aren't many more art comics in Japan than in the United States, regardless of how much more manga there is.

Instead, there's fat pamphlets for mature readers like Big Comic, with stories often as direct as can be, from the ease of an accomplished popular medium. This could be a culture clash, my reservations. It brings to mind a question a reader asked of Grant Morrison during a spotlight panel at the New York Comic Con the other year. The guy didn't think he understood the last (first) issue of The Invisibles.

"Of course you understood it," Morrison replied, "the words were what you read, and the pictures were what you saw."

You can bank on that here, morso than usual, for better or worse.

<< Home