Something big is coming...

*But first, some old fashioned comic book comics; the first one'll show up in stores, at least. Links are for browsin' & buyin'.

***

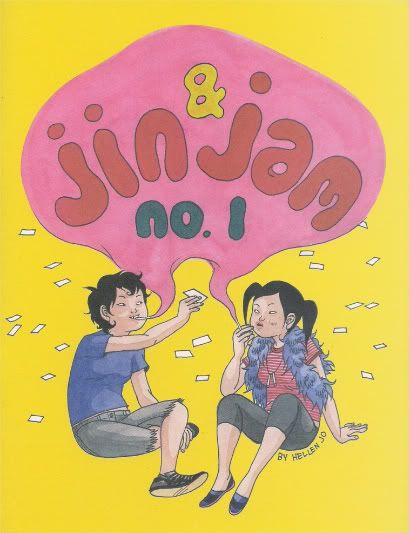

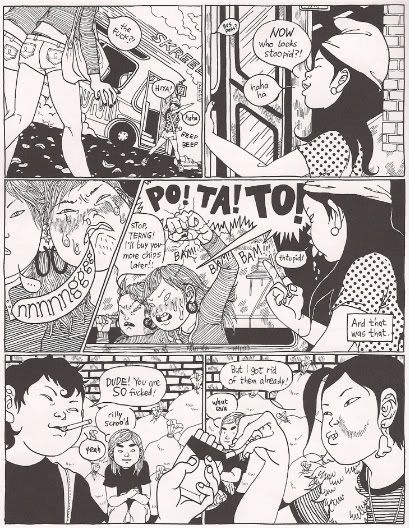

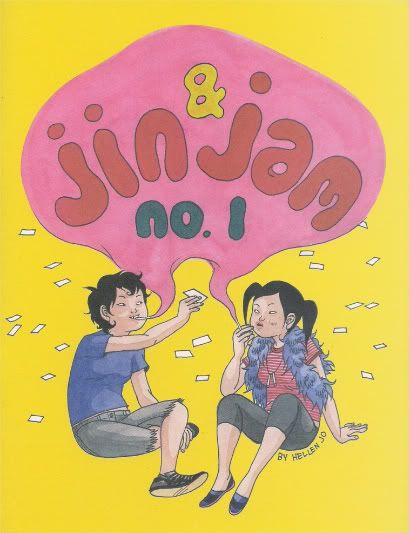

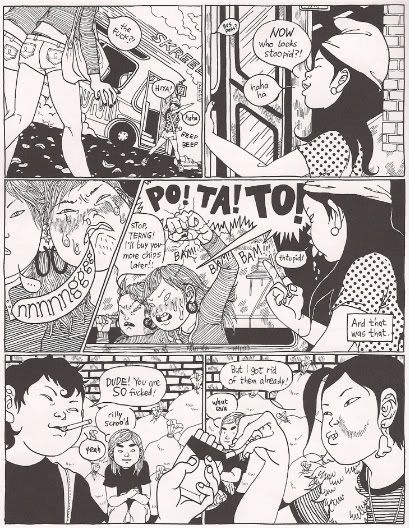

Jin & Jam #1 (Hellen Jo; Sparkplug Comic Books, 36 pages, $5.00): I liked this a lot, although I admit it's got some stuff going on (stuff I particularly liked) that maybe isn't going to be all that apparent to a ton of readers. That's not to say the work's surface qualities aren't nice; at its simplest, it's an energetic prelude-and-chapter-one, all about a pair of San Jose teenagers who bond over smokes and snacks and getting into fights with other girls and generally being happy and shitty. A slice of life with lots of shouting and sneering, and just a little bit of tenderness, conveyed through a visual style that's fine with tossing up a school of fish floating through the air, when the time's right. Perfectly fine.

But the comic also functions as a fairly specific homage to the mangaka Taiyō Matsumoto, and his 1993-94 anti-heroic action saga Tekkon Kinkreet (or: Black and White); Jo even goes so far as to announce her affinity with an opening quote ("We can beat 'em... just you 'n me!"), although even a quick glance at her art reveals a strong Matsumoto influence. But Jo strips away the mythic-generic undercurrent from Matsumoto's work, and transposes streetwise fighter Black's and giggling playactor White's two-fisted adventures in Treasure Town to a mostly realistic venue for less faux-heroic romping and clashes.

Basically, Jo takes part of Matsumoto's subtext and makes it pretty much the whole story (so far), cleverly converting seinen action stuff to something that seems especially personal to her, even as she slips in a few direct cites to the manga, like the Smurf hat seen above, or the aforementioned image of fish. Jin & Jam aren't on a mission to protect San Jose or anything, but its grittier confines are still a good playground, and there's still (momentary) enemies to fight, and while they have other friends and stuff, and you can presume they do all have parents or guardians somewhere in town, their primary shared life's experience at the moment is being cool and impressing each other.

Yet Jo's girls don't get the allegorical credit of Matsumoto's boys - Jin's potential abandonment of San Jose's town o' treasure comes from nothing fancier than wanting to go to college and make something of herself, while the constant presence of SAT flashcards and Christianity in her life anticipates the taking of White by forces of adult authority. No word on Jam's dark side; I suspect it may not involve a minotaur or a labyrinth, though I'm sure it exists!

The visuals are also more grounded, sometimes to the point of awkwardness; Jo's character designs are nice, and she's got a good eye for vivifying situations through creative lettering (perfect for not-really-fantasy-action), but her fights sometimes tend to pose rather than snap, leading to moments where her ideas -- like, say, allegedly conjoined twins who occasionally pop apart in the middle of a fight, only to click back together like like a magnet to a fridge -- appear to be outrunning her chops. Still, I'm confident future chapters will improve, and I'm fascinated with where this 'sitting down for a smoke with a beloved comic' of a comic might go.

***

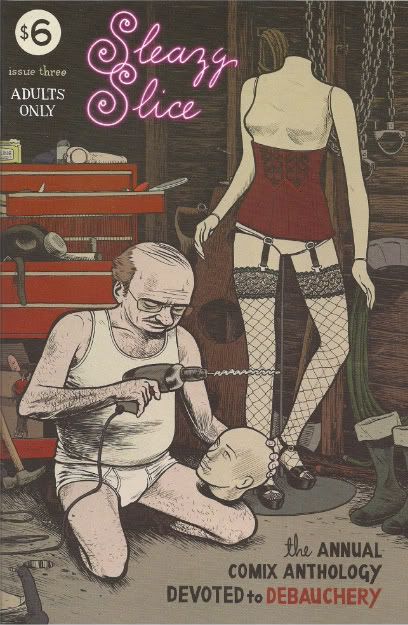

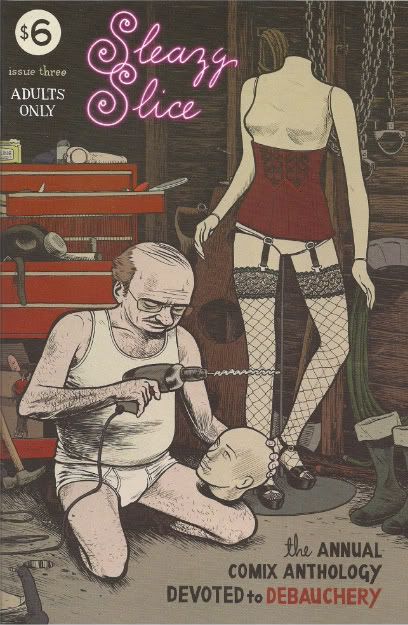

Sleazy Slice #3 (ed. Robin Bougie; self-published, 64 pages, $6.00): Hey, remember last week when I took note of Jamie Delano's Avatar series Rawbone for its excess? Yeah, well, things are relative, and its semi-major comics publisher brand of 'sleaze' has nothing on a thick cut of extra-small press sex 'n violence like this. Editor Bougie is probably better known as the man behind the pamphlet-format oddball movie zine (and FAB Press book) Cinema Sewer -- which has a new issue available at the above link, including a two-page comic with art by this comic's cover artist, Jim Rugg -- but the stories collected in Sleazy Slice are more akin to the stuff of an anything-goes underground anthology or involved fetish webcomics, which is to say they go far beyond what you'd expect from exploitation flicks or obscure live-action porno.

The centerpiece of this issue -- located at the issue's center, even! -- is a new 26-page story by Josh Simmons of House and Jessica Farm. The title is Cockbone, and, sure enough, it involves a fellow with a literal spine in his penis, which is possibly the reason why his semen imparts a euphoric state on those who consume it. And consume they do - poor Bonecock services his whole family, tucked away and blissing out while the world-at-war goes to hell and nourishment becomes scarce. Our Man is a gentle giant, first seen goaded by his brothers into shooting a dog for meat and laffs, but the family fun ends when a sexually transmitted disease demands Bonecock and his mother/lover journey into the outside world.

The art here is highly reminiscent of Chester Brown's work on Ed the Happy Clown, positioning small characters inside dense, sometimes askew panel arrangements, all the better for sedating the gory sexuality at hand into a sort of absurdity, although Simmons is not as interested in overt comedic fantasy. Rather, his dazed hero (w' enhanced appendage) is a naif caught up in parental struggles, just as his world is beat down by a conflict few seem to have control over. And while he shows a heart of steel, it's ultimately futile in Simmons' fallen world, even with the eventual introduction of magic - all the good ones are slaves to disease, sexual, metaphorical and otherwise.

There are a few happier stories elsewhere in the comic, although none of them are quite as interesting, and violence generally intrudes somehow - there's no doubt someone out there will find the work 'useful,' to borrow the friendly manga term, but the main sensation I felt was curiosity over what odd thing might show up next. A silly bodily-functions-as-aliens-piloting-a-ship depiction of anal sex? A pig-horse on centauride gangbang in a cowboy story? A possibly biographical one-pager about a prostitute's oddest client? It's really a bit old-timey in its bottomless desire to present anything, while the visual standard is actually a bit higher than average for an all-porn effort these days.

For his part, Bougie (who gallops his cartoon smile through this and Cinema Sewer like the cheeriest Food Network host ever condemned to hell) saves the most bombastic art assignment for himself, translating the bovine exhibitionist fantasies of one "Petra" to comics form with adept tactility; I won't ruin any of the surprises, but it's definitely the most effective militant vegan quasi-furry lesbian lactation-cum-rape & forced cannibalism specialty comic I've encountered since they cancelled Blue Beetle. You probably won't see this one on your friendly neighborhood New Releases rack, though, so get thee to the link above if you're liking what you're thinking.

***

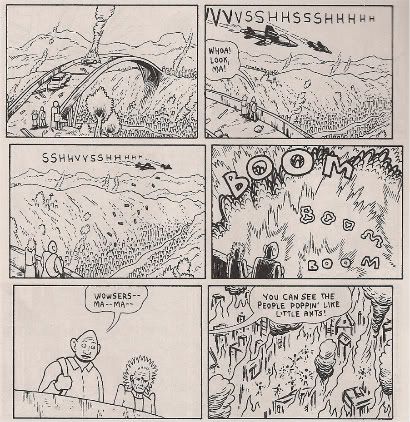

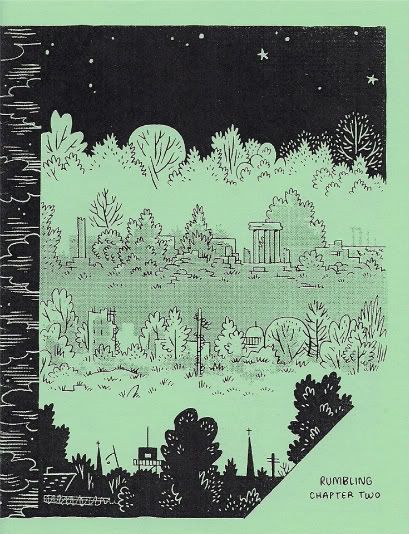

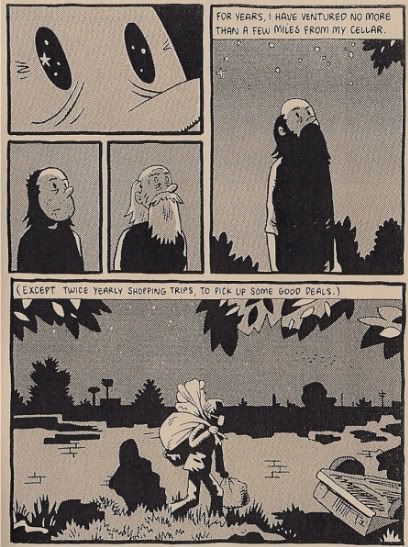

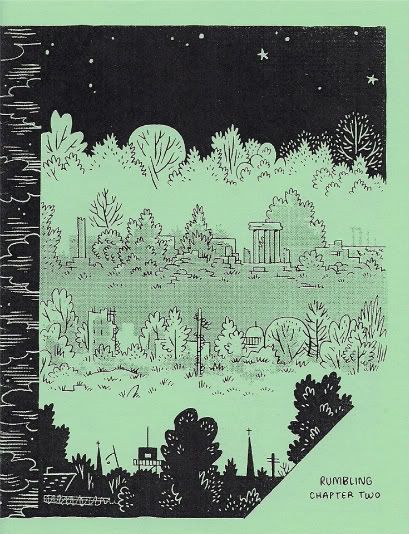

Rumbling Chapter Two (Kevin Huizenga; self-published, 32 pages, $3.00): Being the continuation of the serial Huizenga began in Or Else #5; some people seemed stunned when Huizenga announced that Drawn and Quarterly series' cancellation, but I kinda suspected something was up when I got to the Coming Soon page listing the contents of issues #6-24. Curious readers may be interested to know, however, that this simple minicomic does contain issue #6's promised "record reviews," in that the serial chapter is framed as a historical record being viewed from the future, set off from the main story by the minty green paper used for the cover as seen above.

Rumbling is Huizenga's comics adaptation of a prose story by Italian writer Georgio Manganelli, from his 1979 collection Centuria: 100 Ourobic Novels. I haven't read the book, though I understand that the hundred stories contained therein don't run more than 40 lines apiece, packing ideas and evocation into dense language (here's a review by Harvey Pekar); I expect that kind of prose could prove inspiring to a cartoonist with Huizenga's interest in manipulating time and playing with word-picture interplay, and the continuing comic is indeed delicately furrowed with portals across its timeline and extended dips around particular moments.

The serial's general plot has cast Huizenga everyprotagonist Glenn Ganges as a weary prisoner of a conflict between religious forces in a foreign land; this chapter steers things toward a more specific contemporary U.S. culture war allegory, its nuance steeped in the artist's depiction of scientific reason and religious faith as not so much at war as uneasily sitting beside one another while religion battles other religions and reason shuns the uninvolved. As a result, Ganges, a would-be historian, winds up taking a job as a foreign presence a faith-based society, although he mostly sits around with his nose in a book until a Big One breaks out, at which point he becomes trapped and left to scavenge for items while telling his story - the metaphor is plain.

Given the texture of the language, I presume it's Manganelli drawing equivalence between religious and scientific struggles, a conceptually tidy but socio-politically unconvincing conceit which Huizenga mostly pushes to the back in favor of detailed sequences in which the lost at sea Ganges observes or interacts with religious culture in various states, as if in preparation for arrival of the present as the categorizable past. The particulars get a bit cute in melding Christian and Islamic traditions, but Huizenga has ample opportunity to showcase his typically firm grasp of everyday conversation among risk-adverse persons of different backgrounds, ranging from a busy mother's careful but nonetheless confusing explanation to her child as to why God doesn't talk to Ganges to Our Hero's own blithely obnoxious enthusiasm over riding in a real-live pickup truck.

Of course, this introduction of observational realism does then beg the question of why everyone in this society seems to believe with likeminded violent fervency. Perhaps Ganges isn't much of an unbiased scribe; the framing sequence admits as much in warning the reader that accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed, and future chapters may well shine more light on this "history of the new last days" (which that final Or Else also promised of #6, with arguable accuracy). Huizenga's authorial stamp allows no certainty, least of all from his title, which sometimes rumbles its way across the top of a page, halfway out of sight, marking all work beneath it as its own while behaving like a proper sound effect, omniscient and omnious. If there is a god, it's not a happy one.

***

Jin & Jam #1 (Hellen Jo; Sparkplug Comic Books, 36 pages, $5.00): I liked this a lot, although I admit it's got some stuff going on (stuff I particularly liked) that maybe isn't going to be all that apparent to a ton of readers. That's not to say the work's surface qualities aren't nice; at its simplest, it's an energetic prelude-and-chapter-one, all about a pair of San Jose teenagers who bond over smokes and snacks and getting into fights with other girls and generally being happy and shitty. A slice of life with lots of shouting and sneering, and just a little bit of tenderness, conveyed through a visual style that's fine with tossing up a school of fish floating through the air, when the time's right. Perfectly fine.

But the comic also functions as a fairly specific homage to the mangaka Taiyō Matsumoto, and his 1993-94 anti-heroic action saga Tekkon Kinkreet (or: Black and White); Jo even goes so far as to announce her affinity with an opening quote ("We can beat 'em... just you 'n me!"), although even a quick glance at her art reveals a strong Matsumoto influence. But Jo strips away the mythic-generic undercurrent from Matsumoto's work, and transposes streetwise fighter Black's and giggling playactor White's two-fisted adventures in Treasure Town to a mostly realistic venue for less faux-heroic romping and clashes.

Basically, Jo takes part of Matsumoto's subtext and makes it pretty much the whole story (so far), cleverly converting seinen action stuff to something that seems especially personal to her, even as she slips in a few direct cites to the manga, like the Smurf hat seen above, or the aforementioned image of fish. Jin & Jam aren't on a mission to protect San Jose or anything, but its grittier confines are still a good playground, and there's still (momentary) enemies to fight, and while they have other friends and stuff, and you can presume they do all have parents or guardians somewhere in town, their primary shared life's experience at the moment is being cool and impressing each other.

Yet Jo's girls don't get the allegorical credit of Matsumoto's boys - Jin's potential abandonment of San Jose's town o' treasure comes from nothing fancier than wanting to go to college and make something of herself, while the constant presence of SAT flashcards and Christianity in her life anticipates the taking of White by forces of adult authority. No word on Jam's dark side; I suspect it may not involve a minotaur or a labyrinth, though I'm sure it exists!

The visuals are also more grounded, sometimes to the point of awkwardness; Jo's character designs are nice, and she's got a good eye for vivifying situations through creative lettering (perfect for not-really-fantasy-action), but her fights sometimes tend to pose rather than snap, leading to moments where her ideas -- like, say, allegedly conjoined twins who occasionally pop apart in the middle of a fight, only to click back together like like a magnet to a fridge -- appear to be outrunning her chops. Still, I'm confident future chapters will improve, and I'm fascinated with where this 'sitting down for a smoke with a beloved comic' of a comic might go.

***

Sleazy Slice #3 (ed. Robin Bougie; self-published, 64 pages, $6.00): Hey, remember last week when I took note of Jamie Delano's Avatar series Rawbone for its excess? Yeah, well, things are relative, and its semi-major comics publisher brand of 'sleaze' has nothing on a thick cut of extra-small press sex 'n violence like this. Editor Bougie is probably better known as the man behind the pamphlet-format oddball movie zine (and FAB Press book) Cinema Sewer -- which has a new issue available at the above link, including a two-page comic with art by this comic's cover artist, Jim Rugg -- but the stories collected in Sleazy Slice are more akin to the stuff of an anything-goes underground anthology or involved fetish webcomics, which is to say they go far beyond what you'd expect from exploitation flicks or obscure live-action porno.

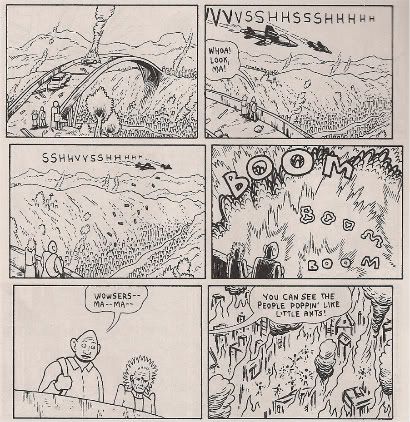

The centerpiece of this issue -- located at the issue's center, even! -- is a new 26-page story by Josh Simmons of House and Jessica Farm. The title is Cockbone, and, sure enough, it involves a fellow with a literal spine in his penis, which is possibly the reason why his semen imparts a euphoric state on those who consume it. And consume they do - poor Bonecock services his whole family, tucked away and blissing out while the world-at-war goes to hell and nourishment becomes scarce. Our Man is a gentle giant, first seen goaded by his brothers into shooting a dog for meat and laffs, but the family fun ends when a sexually transmitted disease demands Bonecock and his mother/lover journey into the outside world.

The art here is highly reminiscent of Chester Brown's work on Ed the Happy Clown, positioning small characters inside dense, sometimes askew panel arrangements, all the better for sedating the gory sexuality at hand into a sort of absurdity, although Simmons is not as interested in overt comedic fantasy. Rather, his dazed hero (w' enhanced appendage) is a naif caught up in parental struggles, just as his world is beat down by a conflict few seem to have control over. And while he shows a heart of steel, it's ultimately futile in Simmons' fallen world, even with the eventual introduction of magic - all the good ones are slaves to disease, sexual, metaphorical and otherwise.

There are a few happier stories elsewhere in the comic, although none of them are quite as interesting, and violence generally intrudes somehow - there's no doubt someone out there will find the work 'useful,' to borrow the friendly manga term, but the main sensation I felt was curiosity over what odd thing might show up next. A silly bodily-functions-as-aliens-piloting-a-ship depiction of anal sex? A pig-horse on centauride gangbang in a cowboy story? A possibly biographical one-pager about a prostitute's oddest client? It's really a bit old-timey in its bottomless desire to present anything, while the visual standard is actually a bit higher than average for an all-porn effort these days.

For his part, Bougie (who gallops his cartoon smile through this and Cinema Sewer like the cheeriest Food Network host ever condemned to hell) saves the most bombastic art assignment for himself, translating the bovine exhibitionist fantasies of one "Petra" to comics form with adept tactility; I won't ruin any of the surprises, but it's definitely the most effective militant vegan quasi-furry lesbian lactation-cum-rape & forced cannibalism specialty comic I've encountered since they cancelled Blue Beetle. You probably won't see this one on your friendly neighborhood New Releases rack, though, so get thee to the link above if you're liking what you're thinking.

***

Rumbling Chapter Two (Kevin Huizenga; self-published, 32 pages, $3.00): Being the continuation of the serial Huizenga began in Or Else #5; some people seemed stunned when Huizenga announced that Drawn and Quarterly series' cancellation, but I kinda suspected something was up when I got to the Coming Soon page listing the contents of issues #6-24. Curious readers may be interested to know, however, that this simple minicomic does contain issue #6's promised "record reviews," in that the serial chapter is framed as a historical record being viewed from the future, set off from the main story by the minty green paper used for the cover as seen above.

Rumbling is Huizenga's comics adaptation of a prose story by Italian writer Georgio Manganelli, from his 1979 collection Centuria: 100 Ourobic Novels. I haven't read the book, though I understand that the hundred stories contained therein don't run more than 40 lines apiece, packing ideas and evocation into dense language (here's a review by Harvey Pekar); I expect that kind of prose could prove inspiring to a cartoonist with Huizenga's interest in manipulating time and playing with word-picture interplay, and the continuing comic is indeed delicately furrowed with portals across its timeline and extended dips around particular moments.

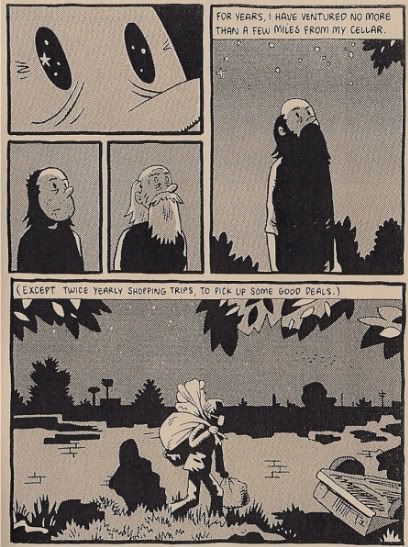

The serial's general plot has cast Huizenga everyprotagonist Glenn Ganges as a weary prisoner of a conflict between religious forces in a foreign land; this chapter steers things toward a more specific contemporary U.S. culture war allegory, its nuance steeped in the artist's depiction of scientific reason and religious faith as not so much at war as uneasily sitting beside one another while religion battles other religions and reason shuns the uninvolved. As a result, Ganges, a would-be historian, winds up taking a job as a foreign presence a faith-based society, although he mostly sits around with his nose in a book until a Big One breaks out, at which point he becomes trapped and left to scavenge for items while telling his story - the metaphor is plain.

Given the texture of the language, I presume it's Manganelli drawing equivalence between religious and scientific struggles, a conceptually tidy but socio-politically unconvincing conceit which Huizenga mostly pushes to the back in favor of detailed sequences in which the lost at sea Ganges observes or interacts with religious culture in various states, as if in preparation for arrival of the present as the categorizable past. The particulars get a bit cute in melding Christian and Islamic traditions, but Huizenga has ample opportunity to showcase his typically firm grasp of everyday conversation among risk-adverse persons of different backgrounds, ranging from a busy mother's careful but nonetheless confusing explanation to her child as to why God doesn't talk to Ganges to Our Hero's own blithely obnoxious enthusiasm over riding in a real-live pickup truck.

Of course, this introduction of observational realism does then beg the question of why everyone in this society seems to believe with likeminded violent fervency. Perhaps Ganges isn't much of an unbiased scribe; the framing sequence admits as much in warning the reader that accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed, and future chapters may well shine more light on this "history of the new last days" (which that final Or Else also promised of #6, with arguable accuracy). Huizenga's authorial stamp allows no certainty, least of all from his title, which sometimes rumbles its way across the top of a page, halfway out of sight, marking all work beneath it as its own while behaving like a proper sound effect, omniscient and omnious. If there is a god, it's not a happy one.

<< Home