"King... I'm glad you're my buddy. Do you mind going to hell with me?"

Color of Rage

This is from Dark Horse, an all-in-one edition of a swordplay manga from 1973. It's $14.95 for 416 b&w pages.

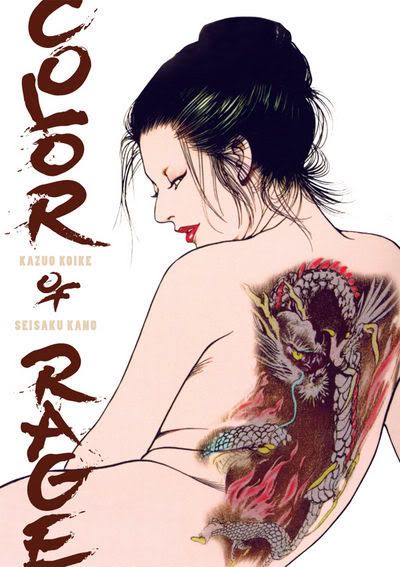

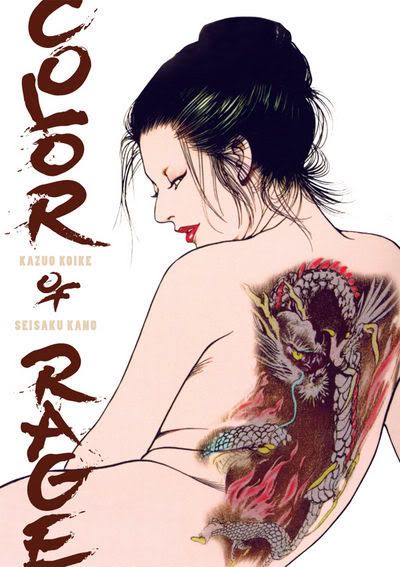

I strongly doubt there's many of you out there that haven't heard of writer Kazuo Koike, he of the famous Lone Wolf and Cub and many other comics about powerful men (and Lady Snowblood) wandering around days of yore and cutting people. He's joined here by artist Seisaku Kano, a frequent collaborator heretofore unseen in English; the team's biggest works appear to be a money-and-girls opus called Auction House (34 vols.), some saucy-looking thing that roughly translates to Experimental Doll Dummy Oscar (19 vols.) and a doubtlessly hot-blooded number titled simply Brothers (9 vols.). Kano has also been active in girlie pin-up art, as the cover up top might suggest.

Color of Rage (which goes by the alternate title Colored inside the book) only seems to have lasted for two volumes, beautifully subtitled Let's Go, My Friend! and God Damn It, My Friend! - I couldn't tell you why, but I can identify some telling differences between this and Koike's other 'period' action comics. For one, while Koike has always strived to provide little educational tidbits in his stories, this is the first of his samurai-type works I've seen to adopt something approaching an overarching academic thesis, that the state of the lower classes in Edo period Japan was analogous to that of slaves held contemporaneously in the United States.

To better illustrate this idea -- and provide many thrills for the waiting audience -- Koike whips up an odd couple premise about a pair of men trapped on a slaving vessel in 1783. One is King, a black man from America, and the other is Jöjirö, a Japanese man known to King as "George." Don't ask how they met or wound up in chains in the middle of the ocean, because Koike ain't telling. Anyway, the ship sinks, and Our Heroes wind up wandering around Japan looking for A Place to Belong.

As such, this is also the first of Koike's works I've seen that features a person of a totally foreign culture as one of the primary characters, who shoulders a large portion of the narrative. And it doesn't go all that smoothly, truth be told... well, let me describe the first chapter.

The epic begins with King and George sinking into the murky depths, which are extra-murky due to what I presume were originally deep oceanic colors being reproduced in black and white. King and George slice the feet off of other members of their chain gang, then swim to shore. A pair of frowning (so: evil) people pass by, and Our Heroes grab their legs and take their clothes.

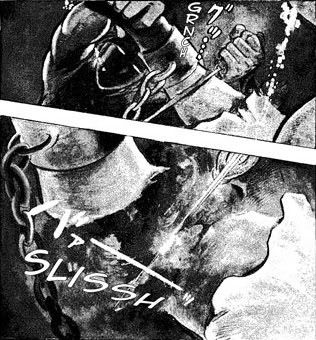

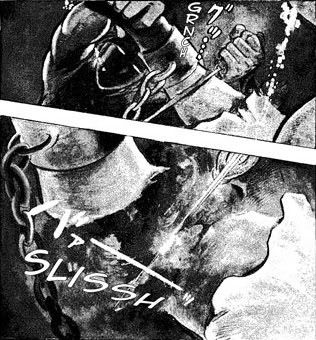

Then there's a flashback to life on the boat, at which point King and George participate in a largely incomprehensible mutiny while the ship sinks; artist Kano has a decent way with gekiga character art -- joining the hewn-from-rock sternness of Takao Saito with some of the inky grace of Goseki Kojima -- and he manages a few nice splashes of sooty page design, but his action staging is convoluted whenever it's not focused on moment-by-moment gesture from a fixed perspective.

Now sitting ashore (again), King and George fashion a makeshift bomb to break the chains binding them to the severed feet, then set off for a way to free their ankles from the remaining shackles. The first blacksmith they find is in the middle of making love to a woman, and George must hold King back from being driven wild at the very sight ("Oh... urr... urr..."). The blacksmith breaks the shackles, but he and the woman are alarmed at King's appearance.

Setting off again, the pair run across a gang of men chasing peasants who've tried to abandon their village because there's no way to eke out a living, a crime punishable by death.

"They're just like slaves then."

"Peasants and slaves are no different."

King grits his teeth as he watches men and children put to the sword, but when the pursuers prepare to rape a young virgin he leaps into battle, George close behind. The villains are killed, but the naked girl is so terrified of appearance that she backs right off a cliff and plunges to her doom. George then informs King that he'll have to hide his face behind bandages to keep the population of Japan from freaking out, and King is understandably angry. But then he thinks of that poor girl falling down, with a panel of waves crashing against the rocks added for emphasis, and he weeps manly tears before covering his face. He and George again set off.

I think it's clear from this that Koike's heart is ultimately in the right place, even as he lacks the command of cultural nuance necessary to keep his work from becoming troubling. King wouldn't be the first Kazuo Koike character to be driven to physical action by the sight of fucking, after all, but there's an especially ugly connotation to that particular image in that context which I don't know if Koike totally grasped, even as it seems obvious to a US reader - I mean, he's an escaped slave!!

Or, it could be that Koike was picking and choosing stereotypes to spice up what would have to act as a sexy swordplay thriller for its readership, trusting that the overall message would offset things.

There's some pretty disquieting stuff in here; one episode, fit for a 42nd street exploitation picture, sees King and George forced to bow for a passing noblewoman's palanquin, which then gets delayed behind a poor family's stuck wagon. King, using his near-superhuman might, lifts the wagon out of the way before the guard can cut their way through. But the noble is piqued, and forces King to lift the wagon back in place, then to strip off his clothes and lift the wagon ever higher as she laughs and laughs. A poor, innocent girl (of course) throws herself in front of King to stop the humiliation, which gets her skewered and sparks a melee that ends with King ripping the noblewoman's clothes off and forcing her to eat mud as he chokes her to death. Koike does manage to restrain himself from throwing in a heroic rape scene, so the business never quite reaches Wounded Man-caliber misogyny, but its mix of sick thrills and attempted social justice is queasy nonetheless.

Should I mention that the chapter ends with King pausing by the wounded girl's door, causing her to miraculously spring awake while King flashes George an 'a-ok' signal? Because this stuff gets as sentimental -- even self-congratulatory -- as Koike cares to be. Another episode has Our Heroes gambling their way up to enough money to rent prostitutes, which leads to a battle with mean yakuza, George lecturing on how prostitutes of the time are also like slaves (he does this a lot), and King pontificating on how he could never exploit a woman like that after the life he's led. "Your words cut my heart like thorns. It cooled me down for sure," smiles George, whom I guess is condescending enough to constantly talk to people about exploitation without ever planning to do anything to stop it, the shit.

All that said, there's some entertainment to be had from this book, particularly once the story hits its second half and a long framed-for-murder storyline allows Koike to work his talents for propulsive plotting. There's not much of an ending, more the suggestion of one, but Koike's concept does manage to tighten just enough to provide a climactic vision of a lone lawmen fighting off all comers in the freezing snow as an allegory for the enlightened man's struggle against the prejudice of a society. I can't call it all that artful, but I do think there's some value in witnessing this type of cross-cultural struggle work itself out on the page, even though, to be frank, you can get better Koike swordplay or eccentric action from a lot of other places.

Oh, there's also a 40-page bonus story about a young punk who runs into legendary swordsman Shimizu Jirocho and learns a valuable lesson about stabbing motherfuckers who deserve it. It's like an Saturday morning end-of-cartoon PSA, only with Flint teaching the kids how to lose an eye like heroes. So at least the book sends the reader away with a spring in the step.

This is from Dark Horse, an all-in-one edition of a swordplay manga from 1973. It's $14.95 for 416 b&w pages.

I strongly doubt there's many of you out there that haven't heard of writer Kazuo Koike, he of the famous Lone Wolf and Cub and many other comics about powerful men (and Lady Snowblood) wandering around days of yore and cutting people. He's joined here by artist Seisaku Kano, a frequent collaborator heretofore unseen in English; the team's biggest works appear to be a money-and-girls opus called Auction House (34 vols.), some saucy-looking thing that roughly translates to Experimental Doll Dummy Oscar (19 vols.) and a doubtlessly hot-blooded number titled simply Brothers (9 vols.). Kano has also been active in girlie pin-up art, as the cover up top might suggest.

Color of Rage (which goes by the alternate title Colored inside the book) only seems to have lasted for two volumes, beautifully subtitled Let's Go, My Friend! and God Damn It, My Friend! - I couldn't tell you why, but I can identify some telling differences between this and Koike's other 'period' action comics. For one, while Koike has always strived to provide little educational tidbits in his stories, this is the first of his samurai-type works I've seen to adopt something approaching an overarching academic thesis, that the state of the lower classes in Edo period Japan was analogous to that of slaves held contemporaneously in the United States.

To better illustrate this idea -- and provide many thrills for the waiting audience -- Koike whips up an odd couple premise about a pair of men trapped on a slaving vessel in 1783. One is King, a black man from America, and the other is Jöjirö, a Japanese man known to King as "George." Don't ask how they met or wound up in chains in the middle of the ocean, because Koike ain't telling. Anyway, the ship sinks, and Our Heroes wind up wandering around Japan looking for A Place to Belong.

As such, this is also the first of Koike's works I've seen that features a person of a totally foreign culture as one of the primary characters, who shoulders a large portion of the narrative. And it doesn't go all that smoothly, truth be told... well, let me describe the first chapter.

The epic begins with King and George sinking into the murky depths, which are extra-murky due to what I presume were originally deep oceanic colors being reproduced in black and white. King and George slice the feet off of other members of their chain gang, then swim to shore. A pair of frowning (so: evil) people pass by, and Our Heroes grab their legs and take their clothes.

Then there's a flashback to life on the boat, at which point King and George participate in a largely incomprehensible mutiny while the ship sinks; artist Kano has a decent way with gekiga character art -- joining the hewn-from-rock sternness of Takao Saito with some of the inky grace of Goseki Kojima -- and he manages a few nice splashes of sooty page design, but his action staging is convoluted whenever it's not focused on moment-by-moment gesture from a fixed perspective.

Now sitting ashore (again), King and George fashion a makeshift bomb to break the chains binding them to the severed feet, then set off for a way to free their ankles from the remaining shackles. The first blacksmith they find is in the middle of making love to a woman, and George must hold King back from being driven wild at the very sight ("Oh... urr... urr..."). The blacksmith breaks the shackles, but he and the woman are alarmed at King's appearance.

Setting off again, the pair run across a gang of men chasing peasants who've tried to abandon their village because there's no way to eke out a living, a crime punishable by death.

"They're just like slaves then."

"Peasants and slaves are no different."

King grits his teeth as he watches men and children put to the sword, but when the pursuers prepare to rape a young virgin he leaps into battle, George close behind. The villains are killed, but the naked girl is so terrified of appearance that she backs right off a cliff and plunges to her doom. George then informs King that he'll have to hide his face behind bandages to keep the population of Japan from freaking out, and King is understandably angry. But then he thinks of that poor girl falling down, with a panel of waves crashing against the rocks added for emphasis, and he weeps manly tears before covering his face. He and George again set off.

I think it's clear from this that Koike's heart is ultimately in the right place, even as he lacks the command of cultural nuance necessary to keep his work from becoming troubling. King wouldn't be the first Kazuo Koike character to be driven to physical action by the sight of fucking, after all, but there's an especially ugly connotation to that particular image in that context which I don't know if Koike totally grasped, even as it seems obvious to a US reader - I mean, he's an escaped slave!!

Or, it could be that Koike was picking and choosing stereotypes to spice up what would have to act as a sexy swordplay thriller for its readership, trusting that the overall message would offset things.

There's some pretty disquieting stuff in here; one episode, fit for a 42nd street exploitation picture, sees King and George forced to bow for a passing noblewoman's palanquin, which then gets delayed behind a poor family's stuck wagon. King, using his near-superhuman might, lifts the wagon out of the way before the guard can cut their way through. But the noble is piqued, and forces King to lift the wagon back in place, then to strip off his clothes and lift the wagon ever higher as she laughs and laughs. A poor, innocent girl (of course) throws herself in front of King to stop the humiliation, which gets her skewered and sparks a melee that ends with King ripping the noblewoman's clothes off and forcing her to eat mud as he chokes her to death. Koike does manage to restrain himself from throwing in a heroic rape scene, so the business never quite reaches Wounded Man-caliber misogyny, but its mix of sick thrills and attempted social justice is queasy nonetheless.

Should I mention that the chapter ends with King pausing by the wounded girl's door, causing her to miraculously spring awake while King flashes George an 'a-ok' signal? Because this stuff gets as sentimental -- even self-congratulatory -- as Koike cares to be. Another episode has Our Heroes gambling their way up to enough money to rent prostitutes, which leads to a battle with mean yakuza, George lecturing on how prostitutes of the time are also like slaves (he does this a lot), and King pontificating on how he could never exploit a woman like that after the life he's led. "Your words cut my heart like thorns. It cooled me down for sure," smiles George, whom I guess is condescending enough to constantly talk to people about exploitation without ever planning to do anything to stop it, the shit.

All that said, there's some entertainment to be had from this book, particularly once the story hits its second half and a long framed-for-murder storyline allows Koike to work his talents for propulsive plotting. There's not much of an ending, more the suggestion of one, but Koike's concept does manage to tighten just enough to provide a climactic vision of a lone lawmen fighting off all comers in the freezing snow as an allegory for the enlightened man's struggle against the prejudice of a society. I can't call it all that artful, but I do think there's some value in witnessing this type of cross-cultural struggle work itself out on the page, even though, to be frank, you can get better Koike swordplay or eccentric action from a lot of other places.

Oh, there's also a 40-page bonus story about a young punk who runs into legendary swordsman Shimizu Jirocho and learns a valuable lesson about stabbing motherfuckers who deserve it. It's like an Saturday morning end-of-cartoon PSA, only with Flint teaching the kids how to lose an eye like heroes. So at least the book sends the reader away with a spring in the step.

<< Home