Every word of this review was planned, considered and written out in longhand this afternoon; what you see now is a perfect transcription.

Jessica Farm Vol. 1 (of 6)

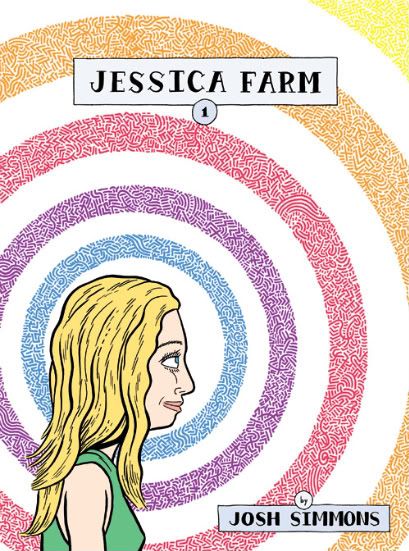

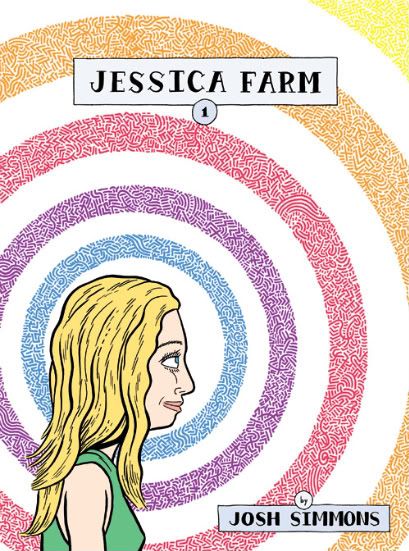

This should be out fairly soon. It's from Fantagraphics, $14.95 for 104 b&w pages. Here is what it looks like from the outside:

It's the new book from Josh Simmons, he who created last year's House, a survival horror-type comic I really liked, dragging a trio of poor souls from the bright, wide-open romantic white of discovery and romance to the broken-up, ruined-body twilight of closed spaces and encroaching blackness that is the end of your days. Life, indeed, is horror. He also made a Batman fan comic of some notoriety.

Jessica Farm will be his life's work. Indeed, he's come up with a schedule so as to ensure that, barring some catastrophe.

Simmons has been working on this story, a fusion of fantasy adventure and psychological horror, since the start of the year 2000; he released a minicomic collection of the stuff a while back. Moving at the brisk pace of one completed page per month, he has now amassed enough content to fill a proper contemporary bookshelf-ready comics tome -- lucky how the market has come around! -- with story page 96 representing the end of December 2007. Future pages will be completed at the same pace, until a total of 600 is reached. The reader is urged to look forward to Vol. 2, set to hit the stands come hell or high water in 2016; the back cover promises that a collected edition will arrive promptly in 2050, for those who'd rather wait.

I like this concept, because it's so off-handedly disquieting. Is Fantagraphics going to publish each volume? Something tells me Gary Groth & Kim Thompson personally aren't, since statistics suggest they'll likely both be dead before the Omnibus Edition hits the presses; there's a merry thought to balance the books by! Here's another: will you be around for all of this? I mean, corporally be around? Do you think? Be honest.

It's like the ultimate in Western comics tardiness -- ironically making it far less likely that the book will ever be late -- married to the most uncomfortable implications of the 'wait for the collection' mentality. Come on - have you ever considered you'll die before, say, Seth finishes Clyde Fans? Simmons forces that thought, and then goes for the punchline: if you do the math, six volumes every eight years won't be enough to hold all 600 pages. The artist is happy to note that the 20-page ending of the story will only be seen in the final collected edition, a consummate serialization dick move that actually doesn't seem very dickish at all when recontextualized like this. Diabolical!

Aw, but I'm playing up the funny consumerist implications here. I'm sure there's a lot more going on down at Simmons' end, since he's creating a record of his own growth as an artist. That's sort of what a 'body of work' is, granted, but this project presents it in time-lapse form, which maybe affords the story's surrealism a greater impact - when every twelve pages represents a year, small multi-page 'moments' are more likely to become charged with shifting style, and all the new concerns a whole 365 days of one's life commands. I think it goes without saying that the plot is heavy on improvisation, although that back cover says it anyway. Almost as a warning.

Funny. I think making shit up as you go along, or at least the illusion thereof, is underrated in those Western comics that might benefit the most from it: steady, longform serials. Freewheeling, here-now-there storytelling -- 'organic,' if you want to be green about it -- can promote vivid spontaneity, a strong notion of the artist's naturally shifting personality, and all the interesting ripples that may issue from liquidity of theme. The relative speed with which the comics medium moves, whether in terms of creation, printing or reading, seems to invite this approach.

But it's superhero comics that make up most of those kinds of comics in the West, are they're typically either beholden to a net of shared-universe cross-references (this event'll put us over the top!!) or conceived as small storylines with an eye toward an eventual, fixed collection, after which the creative team is often replaced. 'Improvisation' may be used, but seems to be acknowledged primarily as a means of hole-filling in the wider saga; band-aids applied quickly to gaping, sucking continuity wounds. I don't know if there's a pejorative connotation at work, but such things are certainly not talked about much in a place where the linewide attunement of many different works is emphasized as a grand, maybe genre-sustaining good. Hell, how could it be?

In contrast, I think some of the appeal of manga comes from the looser type of storytelling employed by Japanese artists, who have the benefit of working within an economic system that allows for long, flowing works from a steady source, capable of bending and shifting to match the artist's will, or even just to make the long haul more interesting to whomever's behind the wheel.

Not all of it's self-expression, of course; some of it's necessity. If you're working on a popular manga serial, especially the shōnen stuff that makes up a big portion of what's out in English, you're probably being bucked around by your editors, frantically waving around reader response forms as if the game show of life has surrendered the host's answer cards. If you're putting out something monthly, weekly - you've got to know how to drift with the currents of reaction, even though you're the only artist (er, you and all the people you've hired as assistants, since we're talking popular manga here), and there's supposedly an ending coming somewhere, although maybe not until Vol. 40 if the brass sees that sales are still up. And when in doubt: fighting tournament!

As such, most of the manga we see in English, in the broadest sense, springs from this mix of personal will and economic survival instinct. It's a novel blend, to us, and in some ways a preferable blend, but if you've got the nasty thought in your head that the Japanese comics industry is some haven for unencumbered self-expression -- particularly based on the stuff filling most American bookstore shelves -- you'd best divest yourself of such triumphalism straight fucking quick because it's not true.

Wait, what's this post about again?

Right. Josh Simmons and time-lapse comics. Good to see a bookshelf-eyeing project embody off-the-cuff values, even if Jessica Farm is too unique in concept to provide much of a model.

As far as execution goes, Simmons does okay. Given that the year 2000 precedes most of Simmons' published comics work, it does make sense that this book's first handful of pages are mostly awful; the title character, a sprightly farm gal, springs out of bed on Christmas morning with rocket glee and hee-haws her way through a too-cute exchange with a talking monkey, all of it ending in bitter irony as her malevolent father pops in to remind her of the hell her life can be. And just as his words seem nice, Evil Poppy is only seen as a shadow wearing big white Mickey Mouse gloves, thus revealing the yawning menace behind the bright iconography of joy, or something in that basic direction. It's very, very banal.

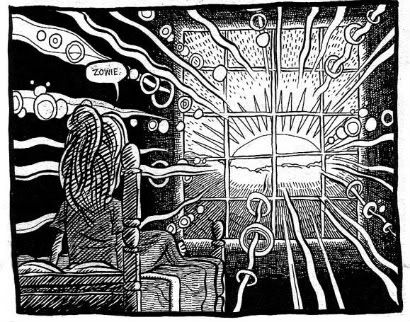

But, as Jessica picks herself up to take her shower and get dressed, months passing in Simmons' life, the story slowly adopts a less adorned mix of fantasy and reality. Avoiding the unwelcome prospect of opening presents downstairs, Jessica wanders the house, checking in with all sorts of odd, magical, perhaps imaginary denizens. Some of them seem to offer Jessica an escape; musical, sexual, etc. All of them are tinged with the anxiousness of a girl on edge, and some of them seek only to remind her of the ugly things lurking in the walls. Sometimes she hurts herself badly, sometimes apparently for fun, although she always seems to heal. She also matures as Simmons' art tightens itself; her accent vanishes and lines begin to mark her face.

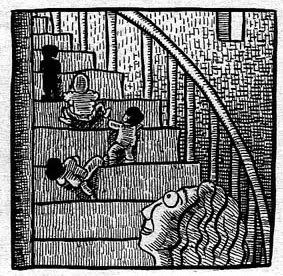

Eventually a plot reveals itself, as Jessica encounters a being that can actually damage things in her house, including her, which sets off a full-scale quest to save the world, involving wise mentors (Gramps 'n Granny), powerful treasures (an arrowhead plucked from her shoulder and made into an amulet), odd creatures (a werewolf guy in a monk's robes) and bold comrades (a naked manservant/bodyguard/fucktoy named Mr. Sugarcock whom Jessica literally leads around by the penis when he's not seasoning dinner by dipping his balls in it).

Could it all still be an externalization of an abused girl's implacable pain? Like the beacons of color shining from her head on the cover? If so, it's a pleasingly detailed one, shifting slightly almost every few pages for another fleeting glimpse of some funny/sad thing, the texture always a little different. Heaven knows that concept keeps the pace up; those years fly by!

But Jessica Farm's makeup ensures that no reading will be very simple. Even when you enjoy the fantasy elements -- and I did, good enough -- you'll always understand that no more of it is readily forthcoming, simply by its state of being. It sure as hell isn't manga. It can seem perverse to have a story like this go on for your whole life, even though its symbol-laden nature (if it even stays in place) will probably do well to soak up the changing state of Josh Simmons. That's the rub, I guess. Maybe it's thinking about how the book's concept pokes and prods at my understanding of how comics can be made and released that's most intriguing to me.

Or maybe I'm lurching around toward a way of pegging down a cruel little fantasy comic like this, fast-moving and slow as age. Maybe you'll want to see how it affects you.

This should be out fairly soon. It's from Fantagraphics, $14.95 for 104 b&w pages. Here is what it looks like from the outside:

It's the new book from Josh Simmons, he who created last year's House, a survival horror-type comic I really liked, dragging a trio of poor souls from the bright, wide-open romantic white of discovery and romance to the broken-up, ruined-body twilight of closed spaces and encroaching blackness that is the end of your days. Life, indeed, is horror. He also made a Batman fan comic of some notoriety.

Jessica Farm will be his life's work. Indeed, he's come up with a schedule so as to ensure that, barring some catastrophe.

Simmons has been working on this story, a fusion of fantasy adventure and psychological horror, since the start of the year 2000; he released a minicomic collection of the stuff a while back. Moving at the brisk pace of one completed page per month, he has now amassed enough content to fill a proper contemporary bookshelf-ready comics tome -- lucky how the market has come around! -- with story page 96 representing the end of December 2007. Future pages will be completed at the same pace, until a total of 600 is reached. The reader is urged to look forward to Vol. 2, set to hit the stands come hell or high water in 2016; the back cover promises that a collected edition will arrive promptly in 2050, for those who'd rather wait.

I like this concept, because it's so off-handedly disquieting. Is Fantagraphics going to publish each volume? Something tells me Gary Groth & Kim Thompson personally aren't, since statistics suggest they'll likely both be dead before the Omnibus Edition hits the presses; there's a merry thought to balance the books by! Here's another: will you be around for all of this? I mean, corporally be around? Do you think? Be honest.

It's like the ultimate in Western comics tardiness -- ironically making it far less likely that the book will ever be late -- married to the most uncomfortable implications of the 'wait for the collection' mentality. Come on - have you ever considered you'll die before, say, Seth finishes Clyde Fans? Simmons forces that thought, and then goes for the punchline: if you do the math, six volumes every eight years won't be enough to hold all 600 pages. The artist is happy to note that the 20-page ending of the story will only be seen in the final collected edition, a consummate serialization dick move that actually doesn't seem very dickish at all when recontextualized like this. Diabolical!

Aw, but I'm playing up the funny consumerist implications here. I'm sure there's a lot more going on down at Simmons' end, since he's creating a record of his own growth as an artist. That's sort of what a 'body of work' is, granted, but this project presents it in time-lapse form, which maybe affords the story's surrealism a greater impact - when every twelve pages represents a year, small multi-page 'moments' are more likely to become charged with shifting style, and all the new concerns a whole 365 days of one's life commands. I think it goes without saying that the plot is heavy on improvisation, although that back cover says it anyway. Almost as a warning.

Funny. I think making shit up as you go along, or at least the illusion thereof, is underrated in those Western comics that might benefit the most from it: steady, longform serials. Freewheeling, here-now-there storytelling -- 'organic,' if you want to be green about it -- can promote vivid spontaneity, a strong notion of the artist's naturally shifting personality, and all the interesting ripples that may issue from liquidity of theme. The relative speed with which the comics medium moves, whether in terms of creation, printing or reading, seems to invite this approach.

But it's superhero comics that make up most of those kinds of comics in the West, are they're typically either beholden to a net of shared-universe cross-references (this event'll put us over the top!!) or conceived as small storylines with an eye toward an eventual, fixed collection, after which the creative team is often replaced. 'Improvisation' may be used, but seems to be acknowledged primarily as a means of hole-filling in the wider saga; band-aids applied quickly to gaping, sucking continuity wounds. I don't know if there's a pejorative connotation at work, but such things are certainly not talked about much in a place where the linewide attunement of many different works is emphasized as a grand, maybe genre-sustaining good. Hell, how could it be?

In contrast, I think some of the appeal of manga comes from the looser type of storytelling employed by Japanese artists, who have the benefit of working within an economic system that allows for long, flowing works from a steady source, capable of bending and shifting to match the artist's will, or even just to make the long haul more interesting to whomever's behind the wheel.

Not all of it's self-expression, of course; some of it's necessity. If you're working on a popular manga serial, especially the shōnen stuff that makes up a big portion of what's out in English, you're probably being bucked around by your editors, frantically waving around reader response forms as if the game show of life has surrendered the host's answer cards. If you're putting out something monthly, weekly - you've got to know how to drift with the currents of reaction, even though you're the only artist (er, you and all the people you've hired as assistants, since we're talking popular manga here), and there's supposedly an ending coming somewhere, although maybe not until Vol. 40 if the brass sees that sales are still up. And when in doubt: fighting tournament!

As such, most of the manga we see in English, in the broadest sense, springs from this mix of personal will and economic survival instinct. It's a novel blend, to us, and in some ways a preferable blend, but if you've got the nasty thought in your head that the Japanese comics industry is some haven for unencumbered self-expression -- particularly based on the stuff filling most American bookstore shelves -- you'd best divest yourself of such triumphalism straight fucking quick because it's not true.

Wait, what's this post about again?

Right. Josh Simmons and time-lapse comics. Good to see a bookshelf-eyeing project embody off-the-cuff values, even if Jessica Farm is too unique in concept to provide much of a model.

As far as execution goes, Simmons does okay. Given that the year 2000 precedes most of Simmons' published comics work, it does make sense that this book's first handful of pages are mostly awful; the title character, a sprightly farm gal, springs out of bed on Christmas morning with rocket glee and hee-haws her way through a too-cute exchange with a talking monkey, all of it ending in bitter irony as her malevolent father pops in to remind her of the hell her life can be. And just as his words seem nice, Evil Poppy is only seen as a shadow wearing big white Mickey Mouse gloves, thus revealing the yawning menace behind the bright iconography of joy, or something in that basic direction. It's very, very banal.

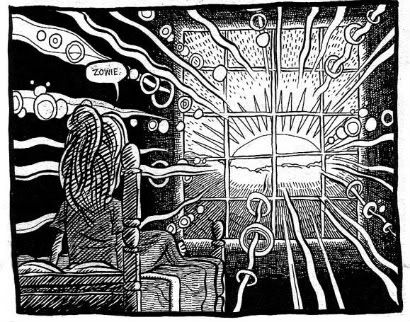

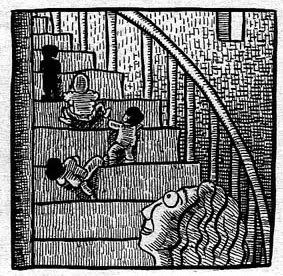

But, as Jessica picks herself up to take her shower and get dressed, months passing in Simmons' life, the story slowly adopts a less adorned mix of fantasy and reality. Avoiding the unwelcome prospect of opening presents downstairs, Jessica wanders the house, checking in with all sorts of odd, magical, perhaps imaginary denizens. Some of them seem to offer Jessica an escape; musical, sexual, etc. All of them are tinged with the anxiousness of a girl on edge, and some of them seek only to remind her of the ugly things lurking in the walls. Sometimes she hurts herself badly, sometimes apparently for fun, although she always seems to heal. She also matures as Simmons' art tightens itself; her accent vanishes and lines begin to mark her face.

Eventually a plot reveals itself, as Jessica encounters a being that can actually damage things in her house, including her, which sets off a full-scale quest to save the world, involving wise mentors (Gramps 'n Granny), powerful treasures (an arrowhead plucked from her shoulder and made into an amulet), odd creatures (a werewolf guy in a monk's robes) and bold comrades (a naked manservant/bodyguard/fucktoy named Mr. Sugarcock whom Jessica literally leads around by the penis when he's not seasoning dinner by dipping his balls in it).

Could it all still be an externalization of an abused girl's implacable pain? Like the beacons of color shining from her head on the cover? If so, it's a pleasingly detailed one, shifting slightly almost every few pages for another fleeting glimpse of some funny/sad thing, the texture always a little different. Heaven knows that concept keeps the pace up; those years fly by!

But Jessica Farm's makeup ensures that no reading will be very simple. Even when you enjoy the fantasy elements -- and I did, good enough -- you'll always understand that no more of it is readily forthcoming, simply by its state of being. It sure as hell isn't manga. It can seem perverse to have a story like this go on for your whole life, even though its symbol-laden nature (if it even stays in place) will probably do well to soak up the changing state of Josh Simmons. That's the rub, I guess. Maybe it's thinking about how the book's concept pokes and prods at my understanding of how comics can be made and released that's most intriguing to me.

Or maybe I'm lurching around toward a way of pegging down a cruel little fantasy comic like this, fast-moving and slow as age. Maybe you'll want to see how it affects you.

<< Home