NOT SILENCE

*I did manage to get a Jeff Smith review out, so that's something. Abhay did a really nice post at the other site too. Dick Hyacinth finished his Ultimate 100 Fusion List.

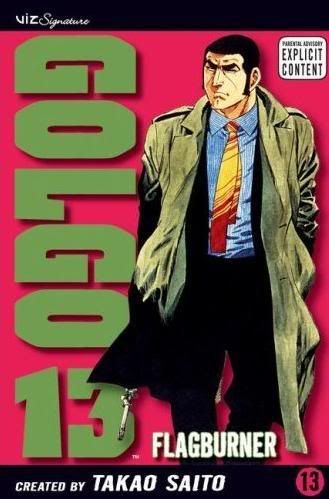

I'm not the first to say it, but gosh - not too much of the ol' manga on there, huh? Less than 10%. There's several reasons for that. My gut tells me a big one for the purposes of a list like Dick's is that VIZ and Tokyopop and the like just aren't as aggressive as, say, Drawn and Quarterly or DC in getting books into the hands of print and wide-focus online media outlets, a situation aggravated by the fact that manga publishers deal primarily in long, continuing series, making it harder to find a 'hook' for the audience when writing a piece for a probably none-too-familiar audience. As far as the comics-focused internet goes, heavy manga sites tend to focus on only manga (or very manga-ish) books, thus booting them from Dick's list, and the same obviously goes for anime magazines that traffic in manga (so, all of them).

That kind of knocks out a lot of possible areas for Best Of action, and every little bit counts with a list set up like Dick's; it's no shock that broad-reaching Vertical's done-in-one Tezuka tomes loom high over the rest, nor that all the manga that 'crossed over' from my list happened to be one-volume projects.

But maybe this is a mere shock from a larger movement happening beneath us. As comics criticism becomes more entrenched in wide-focus venues -- your slick magazines and daily newspapers and pop culture websites -- I suspect the emphasis of coverage will lean even more heavily on books, those things on Amazon and in big chain stores, sent easily and weightily through the mail, familiar and supple in the hands of the wide readership. New graphic novels, yes. Big collections of superhero material, yes. Ropin' and herdin' of small chapters from different places, yes.

For manga in the US, though, the book is not the collection of a series. The book is the series, often released every two months, like clockwork, quick enough and big enough to overwhelm the tired, space-strapped reviewer. It'll be like how there's always less reviews of issue #3 of a superhero miniseries than issue #1, only writ large in the venues reaching for comics as zones of coverage.

It doesn't seem unrealistic to me. It also doesn't bug me, since I don't read all that much of that stuff anyway, but you can bet it'll have an effect on critical consensus things like Dick's list, and perhaps a slow ripple across the growing idea of what the 'best' comics will look like to the wider public.

Meanwhile, I suspect the critical scene surrounding manga-as-manga -- the connoisseurs and crazy fans of whatever 'manga' will embody as a term -- shall develop on its own, on the internet, and maybe other places. What will it look like? How will it engage with the wider world of comics? Will I ever afford a nicer brand of liquor? These are the questions that torment me when I should be at a gym or reminding myself how to present in public. What a wonderful world.

*Hey, I haven't said a thing on Marvel's hot hot deal with French publisher Soleil Productions to release European comics in English, have I? Eh, maybe that's because their first title, due out this May, is Alessandro Barbucci's & Barbara Canepa's Sky Doll.

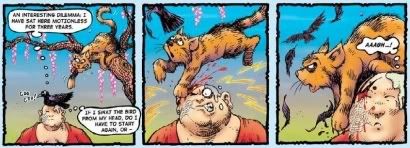

Now, there's nothing really wrong with Sky Doll. It's got a decent enough sci-fi adventure story with a focus on religious/spiritual political struggle. Visually, it's got one of the slicker anime fusion styles I've seen, and I do mean anime; the storytelling fundamentals are straight-up Western density, almost nothing like the poise and flow of most genre-similar manga, but the series has got those candied cartoon stylings down cold for the in-panel designs. Some extra Disney Magic is mixed in too, probably because the creators have worked on some projects for Disney Italy (if Lambiek is right, Barbucci did some duck work too, and he's a teacher at the Italian Disney Academy), but it's extra fitting considering the primordial Disney effect on the anime 'look.' I do believe the creators have cited North and South American comics as influential as well, so let's not get too confined.

But, as a launch book? In Marvel's big attempt to introduce European comics (well, Soleil's) to way more Direct Market reader than would usually have such easy access? It strikes me as odd, for three main reasons.

1. Sky Doll is not finished. I mean, in Europe. I've read this stuff, and believe me - it's at a logical enough stopping point between chapters, yes, but it's not done. And it took six years to get the three extant albums out, the most recent one hitting the shelves in early 2006. Yet, Marvel seems to be pushing it as a three-issue miniseries, which I can't imagine is going to go over well with curious new readers interested in checking out those faintly smutty Eurofunnies, only to find out that there's no ending, nor the promise of one, nor even the promise of more than 44 new pages vaguely in the future (unless Marvel puts out the Spaceship Collection album of short stories). I mean, that can't be how you win over the Direct Market.

2. Oh, the reason I've read the stuff already? Because, contrary to Marvel's claims that the series is "now finally presented in English," the damned thing just came out in the US, from a different publisher, in English, a year and a half ago. I specifically mean the Summer 2006 special issue of Heavy Metal, which collected the whole affair as a $6.95 magazine. Sure, go ahead and joke that Heavy Metal's translations don't count as English - I've read more than my share of head-throbbers, but Sky Doll's localization was merely stiff as a board. They also slapped a Julie Strain metal bikini cover on it, which was charming, but... the material has been released. Hell, a bunch of shops probably have it in their bins somewhere. Maybe Marvel's not counting on their target audience to know, or care. But Heavy Metal... it's not an obscure thing. The stuff's out there.

3. And that raises questions of format. From what I can gather, Marvel is presenting Sky Doll initially in the pamphlet format, at one issue per album, under the MAX banner. Variant cover available! It'll be 64 pages per issue for $5.99 a shot, which suggests that there'll be ads, since there's only 44 pages of story in these things.

Now, like I just mentioned, Heavy Metal isn't the best format ever. It's a floppy magazine, the translation isn't great, the aesthetics aren’t exactly consistent... but, it did present the material in a somewhat oversized format, like I suspect the art was designed to be read in, with no ads to block the flow of each chapter/album, for $6.95.

Meanwhile, Marvel plans to charge $5.99 per issue. At that price point, with that page count, I'll hazard a guess that the format will be typical pamphlet, which means the art will be smaller. Will the ads be pushed to the back? I hope. It'll have the original covers -- unless Marvel gets nervous over anatomy -- and maybe the English adaptation will be smoother, but beyond that it's a total of about $11 more for what might be an even weaker format than the Heavy Metal release. That just doesn't strike me as very clear thinking. Maybe Marvel just presumes its core readership doesn't look at comics not published by them (or DC)?

Anyway, it bugs me. We might probably (hopefully?) get a nice English release of the big ol' collected edition when all is said and done, unless Marvel plans to shoot for the standard North American trade paperback size too. Anyone have more info on this? Maybe instead of ads there'll be bonus features, or some of the short stories. That would make things a lot more interesting...