I readily admit that the Makoto-chan joke in the following post is wholly anachronistic; I beg your forgiveness in advance.

Reptilia

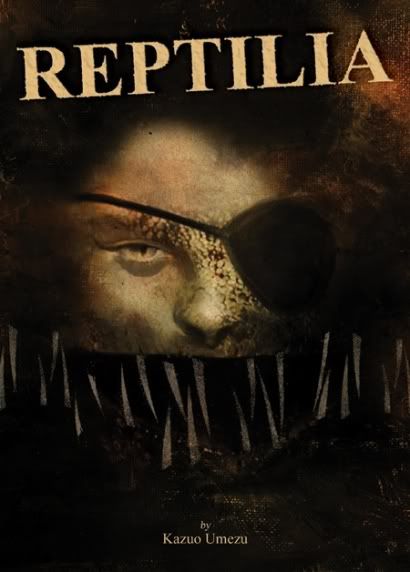

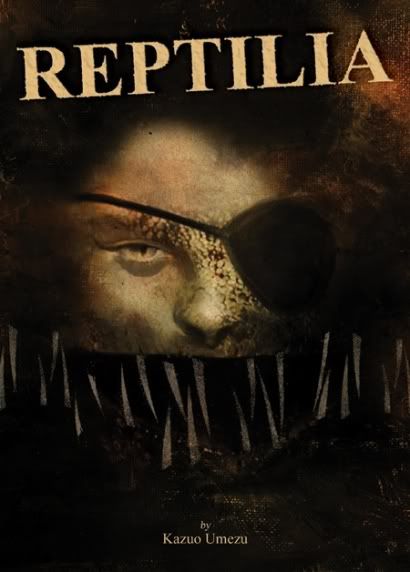

This is IDW's first foray into full-blown manga publishing. It reads right-to-left, the sound effects are not translated (with a pair of word balloons regrettably left empty), and the dimensions leave it slightly wider than the average manga digest. The price is $14.99 for 316 pages. Just as with the publisher's prior localization of a foreign series, Dampyr, there's also a new cover by Ashley Wood.

Although the comic itself has a slightly different flavor.

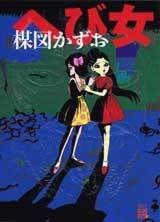

It's by Kazuo Umezu, famous in his native Japan as a superstar romance, horror and humor cartoonist, and just recently 'caught on' in English-speaking environs through his seminal The Drifting Classroom, released by VIZ. It took a few hesitant early US licenses to finally hit the mark, but renown no doubt readily seeks such a man.

Don't expect this to be much like The Drifting Classroom, though. Collecting a trio of stories originally serialized more than four decades ago (1965-66), the package not only predates the man's most famous work available to English-language readers, but hearkens back to an earlier, ill-fated North American Umezu release: Dark Horse's 2006 Scary Book series of context-free horror or horrorish tales, which crawled along for three volumes before blinking from existence.

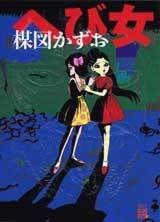

Granted, Reptilia (aka: The Snake Girl, or Hebi Shôjo) is certainly a more important selection from the Umezu catalog -- I do believe it's generally considered his first major horror success -- and it at least has consistency in its favor: its three stories chart the history of a scaaary snake woman who just loves menacing little girls. Tears are shed, pretty dresses are muddied, KYAAHs are exclaimed, and the general threat of being transformed into a gross ugly snake is duly forwarded at every opportunity. If you recall the part in Scary Book Vol. 1 where the little girl protagonist's evil mirror image threatens, with all the moment of prospective ethnic cleansing or the detonation of a bacteriological doomsday weapon, to cut off her beautiful long hair, then you've just about got the tone down.

Hailing from the august pages of Shôjo Friend, the material is vintage girls' horror through and through, hair so smooth and frame so slight, saucer eyes sparkling like a perpetual 4th of July grand finale, the type that goes out of control and injures some poor citizen's leg. I can picture Umezu screaming and cracking a bullwhip at some hapless assistant: "Sparkles, dog! More sparkles!" "But... but sensei... the human eye can only hold..." "Fool! We are not bound by human nor optic concern! Gwashi!" I don't know how traditional the narrative content is, but there's plenty of ooga-booga and shadows, but peace and normalcy inevitably restored by the end.

Manga content hadn't quite broadened to encompass the gnarled shocks that pepper Umezu's best work; the monstrous threats therefore remain mostly that, and the fear element manifests through simple, perhaps stereotypical girl-friendly impulses: fear of ugliness and gross critters runs high. The Drifting Classroom may also be nominally a children's comic, but its hyperactive pace and furious cartooning explode youthful anxieties into grand bursts of nervous mania, with the reader always aware that the madman at the helm might follow through on his threats at any time. As such, it is just the type of 'all-ages' comic that presses against every accepted notion of what the term might mean (VIZ understandably errs on the side of caution and slaps an EXPLICIT CONTENT warning on it), yet, perversely, it embodies the idea. Reptilia, meanwhile, has beasties.

(the empty balloons seen in this post aren't the actual empty balloons in the printed book, by the way)

Still, a fair amount of the Umezu nutrition is present, making this maybe a worthwhile purchase for the devout. The idea of adults refusing to listen to children isn't an old one in horror -- or just about any genre that might appeal to kids, for that matter -- but Umezu remains unique in his vehement disregard for adult authority. All of the 'good' adults in this work are ineffectual, hindering, mobbish, or prone to putting Umezu's child protagonists right into harm's way. And the lady snake figure evoked by the title isn't just a creepy monster - she's both an evil parent and an infection. In one story, a snake lady (there's more than one at work, as Umezu sets up a whole snake history) literally adopts a sparkly lass, all as part of a terrible scheme to revenge herself upon the girl's ancestor. In another, a snake lady replaces a girl's loving mother, turning the whole household against her. The remaining story sees that same girl at the mercy of a group of relatives poisoned by vampiric ways of the snake.

The metaphor actually goes fairly deep. The snake lady's impulse isn't merely to devour little girls, but to convert them into snaky life. That means being real yucky and crawling around in muck, yes, but it also stands for growing up the wrong way; the unspoken pact between parent and child is that the former will not lead the latter astray, and will provide for a healthy future to grow into. The snake lady aims to grow little snake girls into snake women, and thus ensure for them a lifetime of pain and rejection, instead of a bright future; advanced thinking for kids, but maybe not too far from the minds of little girls in '60s Japan, a regimented society with roles to fill, maybe evident from the male-dominated nature of Shôjo manga itself until the '70s. That would also be the day of The Drifting Classroom, where the atmosphere of adult authority's impotence would adopt a fever pitch, and the promise of all the doubting adults snapping into sense by tale's end no longer firm.

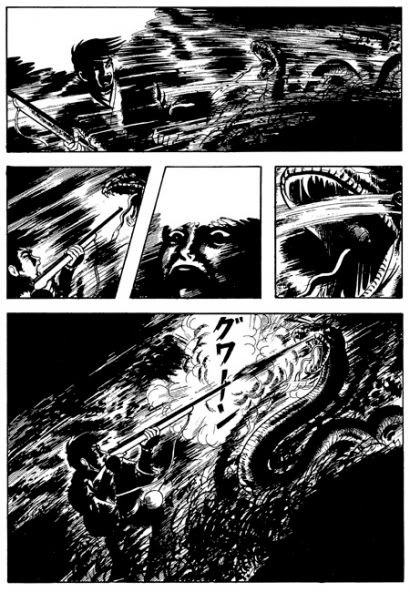

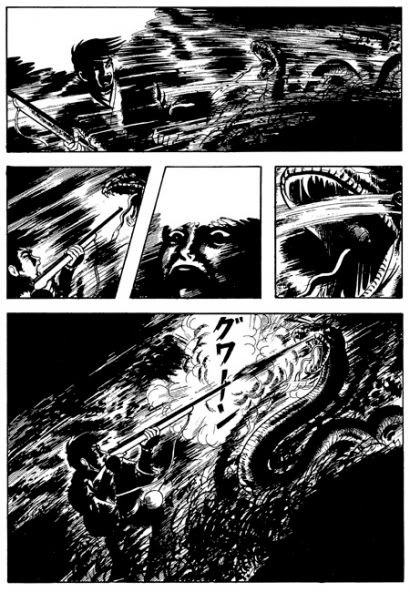

Being a relatively early work, Umezu's art here hasn't yet become so manic and effective. I've never found Umezu's visuals to be quite as stiff as some do - his propulsive storytelling goes a long way toward curing the halting nature of some of his character action. However, the comparatively staid pacing of these stories brings out the stilted nature of some of his action. He does manage some ink-heavy atmospherics, and does show signs of the keen grasp of build-and-release visual action he'd later flaunt, with one particular splash page effective enough that it served as the cover to a Japanese Perfection! edition of the material, although the garish coloring kinda hides all the snakes (and what's the point of that?!).

It's sometimes awkward work, undeniably old-fashioned, and formulaic even within its own contours as a story collection. I suspect there's a lot of smaller, lesser horror works dotting Umezu's '60s bibliography, the kind of stuff that needs a healthy backing of available, major work to bolster it. I wonder if Umezu's Orochi series might provide a bridge; the final installment of the sequence, Orochi: Blood,was the first Umezu work ever seen in English, released by VIZ in 2002. As it went with the artist until recently, no more of the work was ever seen.

It could come back. After all, VIZ's Classroom will be out of session as of April 2008. Although I'd particularly like to see his 1986-89 seinen opus Left Hand of God, Right Hand of the Devil. And hey, I've been begging for his 1990-95 career capstone Fourteen since 2005, although I suspect its 20-volume length might spook publishers more than anyone else. Still, I need more from this man; if we're going this far into the past, I want to see how he existed in approach of the present. Don't leave him stranded, publishers.

This is IDW's first foray into full-blown manga publishing. It reads right-to-left, the sound effects are not translated (with a pair of word balloons regrettably left empty), and the dimensions leave it slightly wider than the average manga digest. The price is $14.99 for 316 pages. Just as with the publisher's prior localization of a foreign series, Dampyr, there's also a new cover by Ashley Wood.

Although the comic itself has a slightly different flavor.

It's by Kazuo Umezu, famous in his native Japan as a superstar romance, horror and humor cartoonist, and just recently 'caught on' in English-speaking environs through his seminal The Drifting Classroom, released by VIZ. It took a few hesitant early US licenses to finally hit the mark, but renown no doubt readily seeks such a man.

Don't expect this to be much like The Drifting Classroom, though. Collecting a trio of stories originally serialized more than four decades ago (1965-66), the package not only predates the man's most famous work available to English-language readers, but hearkens back to an earlier, ill-fated North American Umezu release: Dark Horse's 2006 Scary Book series of context-free horror or horrorish tales, which crawled along for three volumes before blinking from existence.

Granted, Reptilia (aka: The Snake Girl, or Hebi Shôjo) is certainly a more important selection from the Umezu catalog -- I do believe it's generally considered his first major horror success -- and it at least has consistency in its favor: its three stories chart the history of a scaaary snake woman who just loves menacing little girls. Tears are shed, pretty dresses are muddied, KYAAHs are exclaimed, and the general threat of being transformed into a gross ugly snake is duly forwarded at every opportunity. If you recall the part in Scary Book Vol. 1 where the little girl protagonist's evil mirror image threatens, with all the moment of prospective ethnic cleansing or the detonation of a bacteriological doomsday weapon, to cut off her beautiful long hair, then you've just about got the tone down.

Hailing from the august pages of Shôjo Friend, the material is vintage girls' horror through and through, hair so smooth and frame so slight, saucer eyes sparkling like a perpetual 4th of July grand finale, the type that goes out of control and injures some poor citizen's leg. I can picture Umezu screaming and cracking a bullwhip at some hapless assistant: "Sparkles, dog! More sparkles!" "But... but sensei... the human eye can only hold..." "Fool! We are not bound by human nor optic concern! Gwashi!" I don't know how traditional the narrative content is, but there's plenty of ooga-booga and shadows, but peace and normalcy inevitably restored by the end.

Manga content hadn't quite broadened to encompass the gnarled shocks that pepper Umezu's best work; the monstrous threats therefore remain mostly that, and the fear element manifests through simple, perhaps stereotypical girl-friendly impulses: fear of ugliness and gross critters runs high. The Drifting Classroom may also be nominally a children's comic, but its hyperactive pace and furious cartooning explode youthful anxieties into grand bursts of nervous mania, with the reader always aware that the madman at the helm might follow through on his threats at any time. As such, it is just the type of 'all-ages' comic that presses against every accepted notion of what the term might mean (VIZ understandably errs on the side of caution and slaps an EXPLICIT CONTENT warning on it), yet, perversely, it embodies the idea. Reptilia, meanwhile, has beasties.

(the empty balloons seen in this post aren't the actual empty balloons in the printed book, by the way)

Still, a fair amount of the Umezu nutrition is present, making this maybe a worthwhile purchase for the devout. The idea of adults refusing to listen to children isn't an old one in horror -- or just about any genre that might appeal to kids, for that matter -- but Umezu remains unique in his vehement disregard for adult authority. All of the 'good' adults in this work are ineffectual, hindering, mobbish, or prone to putting Umezu's child protagonists right into harm's way. And the lady snake figure evoked by the title isn't just a creepy monster - she's both an evil parent and an infection. In one story, a snake lady (there's more than one at work, as Umezu sets up a whole snake history) literally adopts a sparkly lass, all as part of a terrible scheme to revenge herself upon the girl's ancestor. In another, a snake lady replaces a girl's loving mother, turning the whole household against her. The remaining story sees that same girl at the mercy of a group of relatives poisoned by vampiric ways of the snake.

The metaphor actually goes fairly deep. The snake lady's impulse isn't merely to devour little girls, but to convert them into snaky life. That means being real yucky and crawling around in muck, yes, but it also stands for growing up the wrong way; the unspoken pact between parent and child is that the former will not lead the latter astray, and will provide for a healthy future to grow into. The snake lady aims to grow little snake girls into snake women, and thus ensure for them a lifetime of pain and rejection, instead of a bright future; advanced thinking for kids, but maybe not too far from the minds of little girls in '60s Japan, a regimented society with roles to fill, maybe evident from the male-dominated nature of Shôjo manga itself until the '70s. That would also be the day of The Drifting Classroom, where the atmosphere of adult authority's impotence would adopt a fever pitch, and the promise of all the doubting adults snapping into sense by tale's end no longer firm.

Being a relatively early work, Umezu's art here hasn't yet become so manic and effective. I've never found Umezu's visuals to be quite as stiff as some do - his propulsive storytelling goes a long way toward curing the halting nature of some of his character action. However, the comparatively staid pacing of these stories brings out the stilted nature of some of his action. He does manage some ink-heavy atmospherics, and does show signs of the keen grasp of build-and-release visual action he'd later flaunt, with one particular splash page effective enough that it served as the cover to a Japanese Perfection! edition of the material, although the garish coloring kinda hides all the snakes (and what's the point of that?!).

It's sometimes awkward work, undeniably old-fashioned, and formulaic even within its own contours as a story collection. I suspect there's a lot of smaller, lesser horror works dotting Umezu's '60s bibliography, the kind of stuff that needs a healthy backing of available, major work to bolster it. I wonder if Umezu's Orochi series might provide a bridge; the final installment of the sequence, Orochi: Blood,was the first Umezu work ever seen in English, released by VIZ in 2002. As it went with the artist until recently, no more of the work was ever seen.

It could come back. After all, VIZ's Classroom will be out of session as of April 2008. Although I'd particularly like to see his 1986-89 seinen opus Left Hand of God, Right Hand of the Devil. And hey, I've been begging for his 1990-95 career capstone Fourteen since 2005, although I suspect its 20-volume length might spook publishers more than anyone else. Still, I need more from this man; if we're going this far into the past, I want to see how he existed in approach of the present. Don't leave him stranded, publishers.

<< Home