New and Old to Catch Me Up

However, there's still a ton of books from this year that I haven't posted anything about, even though I ought to. As such, I will make an effort to post about as many of these comics as I can in the remaining days of the year, maybe doubling up short reviews if need be.

*Oh - the second of these two reviews first appeared in issue #283 (May 2007) of The Comics Journal, where it did not have the pictures it has here, and some of the words looked a little different. The first one, though, is new.

Popeye Vol. 2 (of 6): Well Blow Me Down!

There's been a lot written about E.C. Segar's Thimble Theatre, enough so that it might initially seem futile to try and get anything down. This second deluxe Fantagraphics hardcover -- covering December 22, 1930 - June 8, 1932 in the dailies, and March 1, 1931 - October 2, 1932 in the Sundays -- comes decked out with an introduction by veteran strip cartoonist Mort Walker, and part one of a big essay by Donald Phelps, digging good and deep into the Segar approach with expectedly dense, somersaulting prose:

"At last, in the episode of May 8, 1932, the triumphant conqueror, the demon-self of Sappo's fantasy life, enters the tumbled Sappo fortress of conventionality: Professor O.G. Wotasnozzle, the mad inventors' mad inventor; white whiskers reaching, bib-like, the length of his black frock coat, eyes suspiciously a-glaze below or above his perpetually misaligned glasses, mouth even more suspiciously grinning and cackling, to announce the hatching of some fresh illustion-egg."

And that's just in reference to Sappo, a Segar daily strip that wound up 'topping' the Thimble Theatre Sundays for most of the Popeye era, with the titular John Sappo (at that point in the strip's life) cooking up wild inventions, often to the chagrin of his bride. All appropriate Sappos are included in this book (along with a few inappropriate 1924 dailies), and if Phelps sees them as a shimmering, escape-from-domesticity compliment to the 'main' strip's grounded fantastic, I take them as a household burlesque, effectively mirroring the home base setting of the Popeye Sundays - Popeye might beat the shit out of passerby and beasts of the field on a regular basis, but Sappo's childlike zest for creation sometimes results in massive duck casualities, unwitting chickens ground to mush, and a pistol fired multiple times in the direction of Mrs. Sappo.

But this roughness is key to Segar's success as an entertainer, at least as far as these strips go. As I implied above, there's a sort of division between the dailies and the Sundays. Obviously, the dailies offer more involved storylines with a more deliberate narrative beat - that's perhaps a natural product of their initial publication. Yet Segar took that segregation and built on it environmentally; these dailies whisk Popeye and company away to desert locales and foreign lands, for winking suspense and bits of satire. There's villains and wars, and broad canvasses for Popeye to draw on with his fists; he's a real bruising innocent abroad, a uniquely heart-of-America force of impact.

The Sundays, meanwhile, adopt a likeably shambling, "that'll do" approach to storytelling, seeing Popeye's life at home as he punches the hell out of countless old enemies, entertains children, gets into wild prize fights (a giant, a gorilla, a robot), earns and divests himself of huge sums, hangs around at the local café deluxe ("craps shot in rear"), faces multiple incarcerations, and vies for the heart of Olive Oyl. Popeye's landscape nicely compliments his activities, being a plainly depressed urban stretch, drunks and grifters littering the steps and side roads, and even the occasional park acting as a platform for sudden ass-kickings. Segar may be noted for his dialogue and characters, but here he's marvelous at place; if Popeye is an American force, his Hometown, America is depicted as just the place where he might thrive before drifting off again.

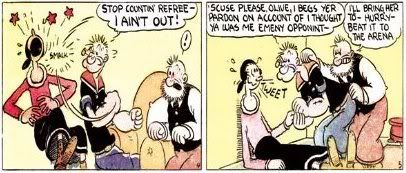

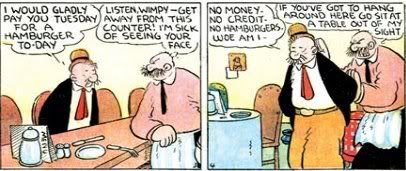

I'm sure I don't need to detail how good Segar's gags are, or how vivid those characters can be. This volume sees the debut of the famous J. Wellington Wimpy, Popeye's opposite number - soft, slothful, gluttonous, pandering, traditionally articulate, and willing to go to paradoxically great lengths to avoid honest gain. He's often brilliantly funny, and another example of a Segar creation that seemed to debut out of a random whim (he's initially a funny referee at one of Popeye's prize matches), and swiftly got locked into place as a fixed (yet evolving!) comedic creation.

That his presence in this volume is locked down to the Sundays is no surprise; one can easily imagine Segar treating his different days -- different places -- as accommodating for the different ways he might use his still-new lead sailor, and thus exclusive from one another. But just as Popeye showed up one day and simply refused to leave, so would other creations be allowed some freedom to roam.

Glacial Period

This isn’t Nicolas De Crécy’s first work to be translated to English -- he’s made a few significant anthology appearances, from the presentation of his and Alexios Tjoyas’ Foligatto in the March 1992 issue of Heavy Metal, to a recent, exemplary contribution to the excellent Fanfare/Ponent Mon anthology Japan as Viewed by 17 Creators -- but many readers will be forgiven for the name not perking them up. Hopefully this book will go a ways toward remedying that; it’s not a sprawling, dazzling work, but an exemplary light comic.

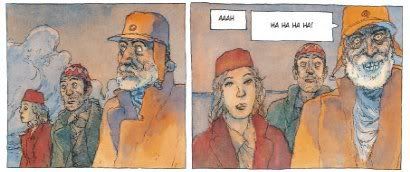

Part of a series of books designed to showcase different artists’ visions of the Louvre, Glacial Period sees a cadre of far-future explorers wander around a frozen landscape in search of a lost metropolis, eventually stumbling into the buried remains of the famed museum. None of them are aware of the true history of humankind, and all of them bring their own prejudices to the works of art they behold, from the cackling old team leader who sees only the crudity of animal scratching, to the romantic marker boy (seemingly a caricature of De Crécy himself) who’s determined to arrange the paintings into a proper sequential narrative of the rise and fall of the past. Their condescension is palpable, if friendly.

Meanwhile, one of the team’s genetically engineered talking dogs, armed with a nose that can literally sniff out historical continuity, chit-chats with famed artistic works from across the centuries that have been in hibernation, away from the changing context of life. That’s not wholly metaphor - the artworks can walk and talk as well. Groups of Jesus icons hang around waiting for a warm body to evangelize toward, and Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn’s 1655 The Skinned Ox stalks the halls like the monster out of an old chiller. It will come as little surprise that this setup eventually stretches into a hearty affirmation of the adaptive power of lasting art, with the more potentially challenging symbols explained right on the page.

But De Crécy’s keen sense of play is always palpable, and his visuals are very fine, deftly integrating classical works into his personal visual style, while knowing when to play up their otherness. Good enough a state for a book that posits the slippery appeal of aged art as a convivial aspect of the fiction of history. Quick and flip, and oh for more whimsical things like it.

<< Home