CBABIH 0.5 - Show Notes

Being a series of comments on Episode 0.5 of Comic Books Are Burning In Hell, a podcast by Matt Seneca, Tucker Stone and, in a surprise twist, Chris Mautner, as well as myself.

00:00: In retrospect, this sounds like some sort of haplessly self-aggrandizing mock warning about the tone of the discussion to follow -- better put the kids to bed, we got a barn burner folks -- but actually I'm just acknowledging the fact that children really are sleeping elsewhere in the Pennsylvania studios of Comic Books Are Burning In Hell, so we can't just start screaming and jumping around over the Civil War prose novel (our unexpurgated dramatization of which can be expected in your local movie theater via Fathom Events as soon as they send the contracts over). As always, I trust the humor value of a joke is directly proportional to its literalism.

00:22: Chris was actually privy to the planning of this pounding pustule of a podcast, true believer, but our eventual decision to just say fuck it and start up with these 0.whatever episodes happened so quickly we didn't immediately have a way to work him in. Episode 0.5, thus, was recorded on the night of June 10, in the basement of Chris' home, so that he and I were on one side and Tucker & Matt were on the other. The audio quality is actually pretty good, save for a few drops in the Brooklyn pickup, though we're still not officially launching; I personally think the addition of another person to the conversation stretched the topics out a little ways beyond where we'd expected, and probably encouraged a bit too much individual speaking and not enough interaction. No word from my therapist on what all of these basement locations mean, but the smart money is always on my penis (which makes grocery shopping fun).

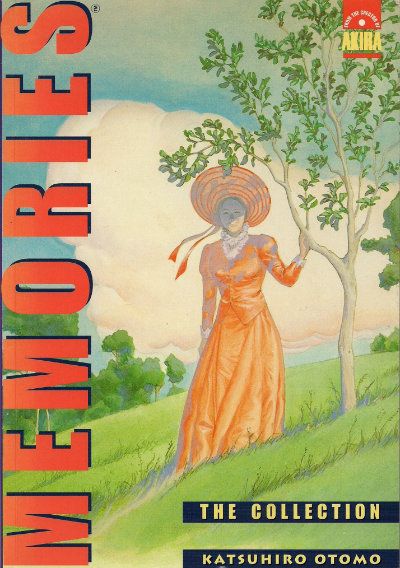

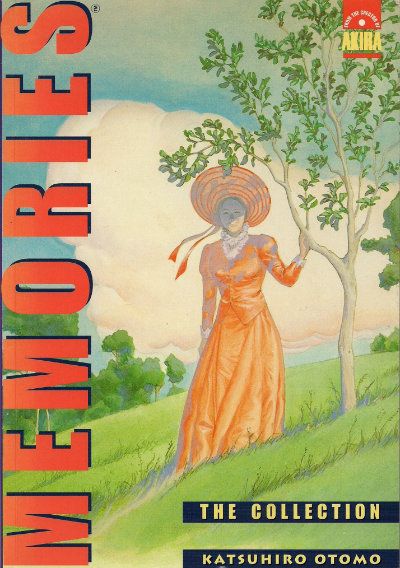

00:40: Memories: The Collection, by Katsuhiro Otomo. Since Tucker's gonna bring it up later, the ISBN number is 0 7493 9687 3. Copies used to be kind of crazy-expensive, but they either dropped in value a bunch lately or I happened to get lucky - I snagged one for just over $20.00 after shipping. The contents are:

Sound of Sand (1979)

Hair (1979)

Electric Bird Land (1980)

Minor Swing (1977)

That's Amazing World Part I & II (1981)

Memories (1980)

Flower (1979)

Farewell to Weapons (1981)

Chronicle of the Planet Tako Part II (1982)

Chronicle of the Planet Tako (1981)

Fireball (1979)

That's Amazing World Part III & IV (1981)

All years come courtesy of this excellent French-language Otomo fansite, which identifies the book as a direct localization of Otomo Katsuhiro Anthology 1, a 1990 Japanese release, albeit with the addition of Marvel/Epic's 1992 Steve Oliff colorizations of Memories and Farewell to Weapons, which I suppose required some reorientation of the contents for technical accommodation, although I still have no idea why the Chronicle of Planet Tako sequel comes before the original. Hair, however -- a parody of Fireball -- went before its inspiration in the Japanese edition as well.

01:15: For the life of me, I still can't recall where I heard of Otomo's antipathy toward English publication of his earlier works; it's probably received wisdom passed along by superfans and publisher reps on message boards. Some of his earlier Japanese collections do appear to remain in print today, though others have vanished; in the interests of clarity, Otomo Katsuhiro Collection 1 was not a repackaging of earlier books, but apparently the start of an effort to compile Otomo's remaining short form works. A second volume was released in 1996, and has not been translated; I couldn't tell you why, save for another vague gesture in the direction of the licensor's reluctance.

01:31: I'm referring here to Yoshiharu Tsuge, one of the titans of alternative manga, and absolutely notorious for his lack of interest in foreign editions of his work. So far the entirety of his formally published oeuvre in English appears in RAW Vol. 1 #7 (Red Flowers), RAW Vol. 2 #2 (Oba's Electroplate Factory) and The Comics Journal #250 (the immortal Screw-Style), although some online translations are out there. Ego comme X also released a French-language edition of Tsuge's Munô no Hito (as L’Homme sans talent) in 2004, which Tsuge purportedly disliked (again: anecdotal).

02:20: The Memories anime actually came out in 1995. It consists of three segments: Magnetic Rose (freely adapted from the Memories manga by the late Satoshi Kon; directed by Koji Morimoto); Stink Bomb (written by Otomo and directed by Tensai Okamura, under the supervision of action maestro Yoshiaki Kawajiri; I like how I dropped fucking Wolf's Rain in there like ANYONE remembers it); and Cannon Fodder (written & directed by Otomo himself).

03:14: I'd like to formally apologize again and in writing to the nation of Germany, and the very kind German man who gave me such a good price on my book. Still, shit takes forever, this isn't the first time!

04:15: Of course, I mean the Kodansha edition of Akira Vol.1, not the Dark Horse version or anything relating to Ghost in the Shell - just settle in, this ain't the last correction today.

04:40: Specifically, for Chronicle of the Planet Tako, Otomo writes:

"Looking at it, I seem to remember that I wrote this with someone else. But as to who it was... Who drew the pictures? If they happen to read it here, would they please contact me. Well, whatever I say, they'll be annoyed. Sorry!"

That's the entire introduction. Tucker is thinking of the intro to Memories, where Otomo alludes to someone named "Takadera" who apparently drew a major splash image for the story... unless Otomo is talking about a much smaller rose image in a different splash. As the "wrote" and "drew" in the above quote indicates, the translation quality of Memories: The Collection is slightly dubious, beginning with a bit in Otomo's Introduction where he's translated as stating:

"This is my seventh collection of short stories in eight years."

and, shortly thereafter:

"Yes, I know, that's a hell of a gap between issues. Truth is, I've been working on Akira all this time, but if things had gone a little more smoothly, it would have been nice to publish some different work before beginning Akira..."

Going off the publication histories of these books -- Boogie Woogie Waltz was released in 1982, the same year Akira began serialization -- it's evident that Otomo is actually saying something to the effect of 'This is my seventh collection of short stories, and the first in eight years.' Not that I'm a brilliant editor or anything, or even that these publication dates were widely available to English speakers in '94, but it does tend to raise doubts about the whole enterprise, at least commentary-wise.

"...I decided to write about sand 'cause it's simple" is a direct quote from the intro to Sound of Sand.

05:59: If I can expand on this a little, it now occurs to me that Otomo's work does have a unifying concern: the inscrutability of vast power. Just as the poor astronauts in Sound of Sand are devoured by the very ground of an alien world, so are the yet poorer astronauts in Memories compressed by the magnetic rose into the nostalgia of the derelict spaceship: a literal pulp sci-fi threat ensconced in metaphor, 'memories' as the obliteration of everything real and current in the nostalgist's wake. Minor Swing, which Tucker later mentions, destroys its protagonist through pollution, which is represented as an endless, unstoppable river of oil. From such industrial calamities it's only a short jump to the computerized cities of Hair and Electric Bird Land, and the most perfect expression of this device: explosive psychic power a la Fireball, Domu: A Child's Dream, and Akira.

Interestingly, Otomo becomes more willing to allow the peril of such power to be challenged in his longer works, in that heroic characters eventually manifest incredible power of their own. The deranged old man of Domu is dispatched with nearly comedic ease once he's faced with his child rival on fair ground, and the youth gangs of Akira eventually cope with the collapse of their dystopian society and the release of incredible psychic force by setting up their own isolationist collective; the potential for revolution, then, embodied by Otomo's many revolutionaries, is the countervailing power that manifests in a more focused state to defeat the capriciousness of older energies.

Yet as short anime like Stink Bomb or the Otomo-written Roujin Z demonstrate, the new power can just as often function as a chaotic element, while the denizens of Cannon Fodder simply march through their endless war against an equally aged (if not imaginary) foe; more specifically politicized critiques can be found in Otomo's segments of the Robot Carnival anthology and his 2012 short comic DJ Teck * Morning Attack, where the forces of the first world raise cloyingly good-intentioned hell in Arabesque locales. Perhaps it takes a while for revolution to concentrate; in this way, Otomo's longer works perhaps analogize a sense of hope to his sad vignettes.

The depth of Farewell to Weapons, then, is in the ambiguity as to whether the drone attack is an old or new power, and the suggestion that it may not matter in such a militarized scene.

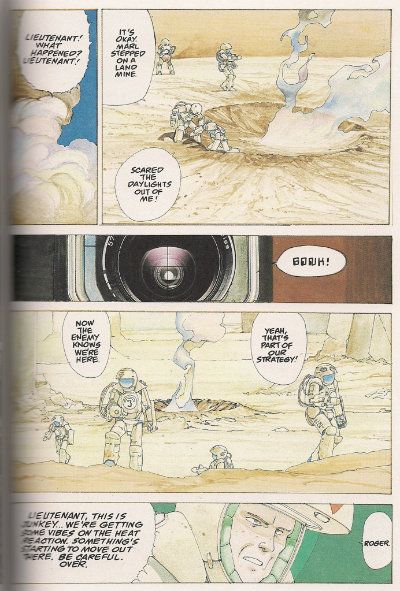

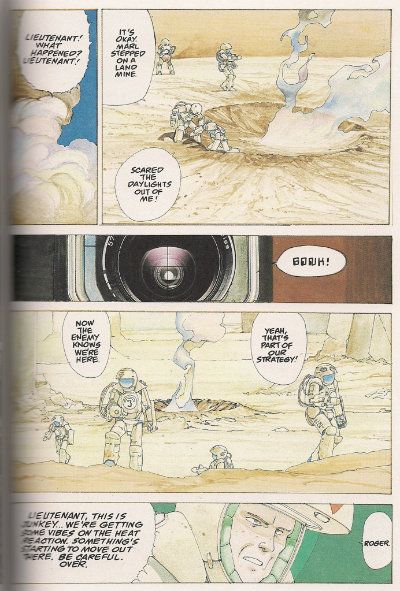

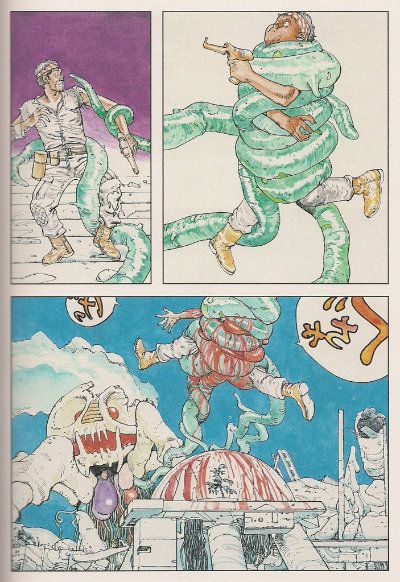

09:57: Just to illustrate, here's Oliff:

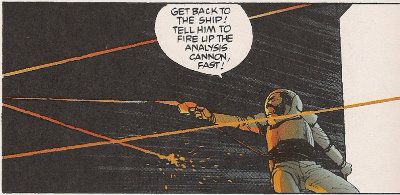

and Otomo, on the following page:

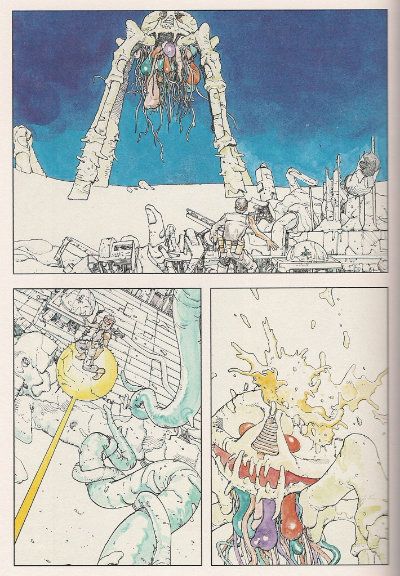

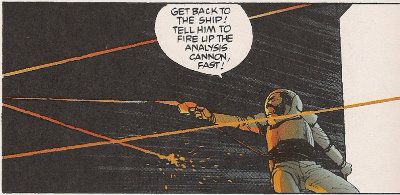

10:52: As promised (detail; the binding's tough):

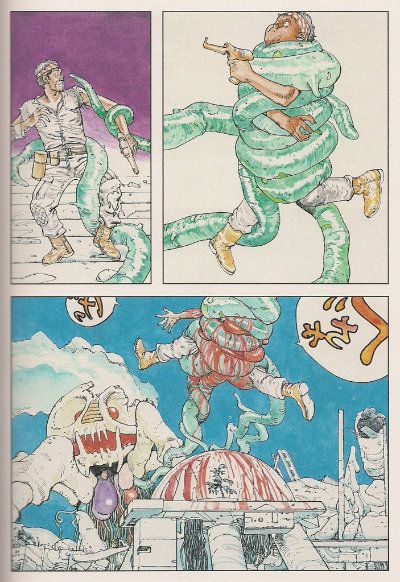

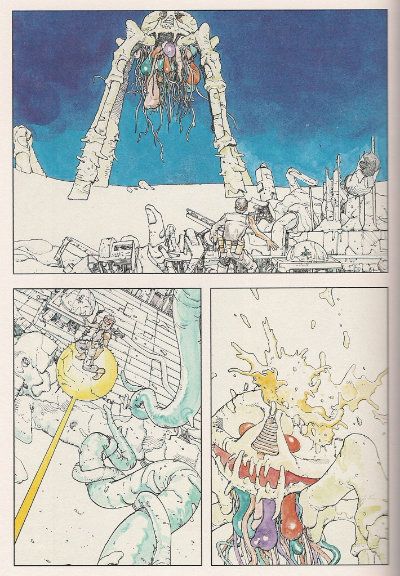

11:17: Ah, what the hell:

Otomo and/or his editor helpfully note(s) in the introduction that the word balloons translate to "HAARGHH" and "GURRGK," respectively.

11:58: This is completely wrong, as evidenced above; all the stories in Memories: The Collection come from a five-year stretch from 1977-1982. I kept thinking Memories itself was made in 1990, which is the year Jason Thompson's Manga: The Complete Guide attributes it to, although it seems that was actually the year it was first collected into book form. Unless my new information is also wrong; this is the problem with not reading Japanese, you're drastically limited in your sources.

13:23: Otomo's Batman story, The Third Mask, first appeared in Batman: Black and White #4, Sept. 1996, and (obviously) appears in the various Batman: Black and White hardback and softcover collections. It has apparently been reprinted again, in some form, via Otomo's 2012 art book Kaba2.

14:32: Here's the UK edition front cover (did you like how we totally set up our cliffhanger ending?):

Matt is correct, it was originally a wraparound image; the full version can be seen here.

18:51: My comments on Otomo's relative 'mainstream' appeal in Japan are somewhat speculative, since I don't have any first or secondary sources on his work's domestic reception in the '70s. I can say, though, that we was part of a small wave with Jirô Taniguchi (another eventual Moebius cohort) and Yukinobu Hoshino (fellow traveler in pulp sci-fi kicks), or even the '60s Garo-bred Ryoichi Ikegami (who initially worked in a considerably cartoonier style) in pursuing a comparatively 'realist' visual approach that might be deemed Western - a deliberate effort in Otomo's case, at least.

Otomo did work on a few shorter serials prior to Akira (which began in '82); besides Domu, there was Sayonara Nippon (1977-78, a karate instructor in New York) and Seijaga Machini Yattekiru (1979, tales of jazz), which were presented together in the 1981 Sayonara Nippon collection. Not in English, of course!

20:07: That's 1991 for World Apartment Horror. Please consider my participation in this episode as a work of conceptual art challenging the presumption of authority in critical dialogue.

22:22: Supervillain fans will note that Mort Weisinger is the other guy in Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the Comic Book that comes off as completely horrible, although the stories just don't compare to Kane's. There's a great bit where Arnold Drake finds out that an artist is suing Kane for her anonymous work on clown paintings he'd been slinging around Hollywood, and Drake goes "He even had a ghost for the fucking clowns!"

23:25: Batman: Death by Design, by Chip Kidd & Dave Taylor. SYNOPSIS: A whole lot of major stuff is going wrong in an early 20th century design wonderland-ish Gotham, like cranes toppling over and shit, so Batman is on the case while some lady who wants Bruce Wayne to preserve a Penn Station-style historical landmark routinely gets herself into trouble. A crusading newspaper critic, a blowhard aesthete, a veritably top-hatted mustache-twirling union boss and the Joker (as: the Joker) are all involved, as is a mystery superhero(?) who might have a hidden connection to a recently-disappeared, long-disgraced architectural genius...

Did you like that? I keep feeling like we don't lay out what these comics are about before we dig into them, so I might just start putting that stuff in the show notes...

24:10: Taylor's Riddler project with Matt Wagner was 1995's Batman: Riddler - The Riddle Factory, colored by Linda Medley of the imminent Castle Waiting. Listener Michel Fiffe also draws attention to a 1999-2000 series Taylor did with writer Karl Kesel, Batman and Superman: World's Finest, where the artist was eventually joined by fellow Judge Dredd alum Peter Doherty (although Taylor didn't work on Dredd until afterward). The Alan Grant stuff I'm thinking of is a slew of Batman: Shadow of the Bat issues from '96-'97, #50-64, barring #55 and #61 (which was pencilled by Tucker Stone favorite Jim Aparo).

24:36: I feel the need to clarify that the character in question is not named "Chip Kidd," though it is obviously using Kidd as its photo reference basis.

31:22: The Journal's archives are down, and my Google cache wizardry isn't sufficient to locate the ¡Journalista! link to which Tucker refers. Anyone have it on hand?

34:14: If you'll allow it -- and of course you will, I've chloroformed you and I'm whispering into your ear, that's why you can't control the words -- I can probably offer a more sympathetic reading of Batman: Death by Design going off Matt's thought balloon comment. Because: thought balloons! Not always popular, and Kidd feels the urge to not only partake, but chow down on especially rich and cheesy variations, in which characters' most intimate, true feelings expound pregnantly above their heads, in pained silence.

You could argue, perhaps, that it's not so much what's written here as what you can see, or even feel - a pleasure of the delicious artifice itself, like sleek art deco buildings are pleasurable, like Ayn Rand superheroes are barking and smart, like old movies are textural, sensual, like how the photographs in Chip Kidd's books always seek to isolate every grain of the paper, every dot of that fine classic coloring, every nick and spot on a beat tin toy. This stuff is cool, the book says, because it's so fucking cool. Look at it! This is what I love, and here's its fictive-curatorial presentation, shorn of distracting context and dressed in only the socio-political implications you bring yourself - this is design, its function to glow inside you. Maybe this is a uniquely powerful function in superhero comics. Maybe its the very basis of superhero momentism, with the idea of cool characters and cool action transubstantiated into cool looks; not a common trick in a genre that's come to value plot over anything else.

The most immediate problem, however, with this type of reading, is that an adequate response is to say nothing more than "I've seen cooler."

40:16: That's Planetary #7. As is becoming a recurring motif in this week's notes, I can't recall where I heard Ellis relate this anecdote; it was likely on one of his message boards. Jesus, I totally shouldn't have made fun of Otomo's notes...

42:23: Matt's saying "Josh Simmons," in reference to that artist's unofficial... 'fan' comic, presently collected in The Furry Trap from Fantagraphics. Batman: Absolution was a hardcover (later softcover) graphic novel from 2002, painted by Brian Ashmore; if you were in the room with us, you'd have seen Chris' ears perk up at the very mention of J.M. DeMatteis, who wrote many favorites of his youth. "NO, WHICH ONE IS THAT?"

45:06: Before I could even sit down to write this post, an alert listener/potential Norm Breyfogle fanatic wrote in to mention that 1991's Batman: Holy Terror -- not to be confused with Frank Miller's 2011 Holy Terror, initially drawn in part as a Batman comic -- was in fact written by Alan Brennert, "actually a pretty good writer of that time period," who went down in history as the very first writer to follow... Frank Miller, on Daredevil; he later gave some assistance to Dennis O'Neil, whose own run as writer included a Matt Seneca favorite. I love it when a note comes together.

47:20: Much more about François Schuiten's & Benoît Peeters' Les Cités obscures can be found at the (French-language) Urbicande site, while Sequart's Julian Darius has been gradually updating a series overview for the English reader. I love these comics to pieces, though they've fallen into the Moebius zone of 'not enough readers on hand to justify the licensing costs, too many readers for used copies to accommodate,' resulting in high prices for NBM's mostly out-of-print English editions.

48:38: One thing I forgot to mention is that Taylor does use color in a somewhat similar way to Schuiten on one of the Les Cités books, 1987's The Tower -- if you can't find the NBM album, Dark Horse serialized the story in issues #9-14 of its Cheval Noir anthology though be warned that Schuiten does not shrink well -- where color is used sparingly as both a striking visual and a seemingly diegetic source of illumination. Granted, Schuiten does this in an 'impossible' way, so that color appears to radiate onto characters' b&w faces in furtherance of his and Peeters' themes, while Taylor adopts a more realistic approach of city lights and flame, etc., but the slight similarity is nonetheless interesting, given the architectural theme.

50:30: "[T]he whole controversy thing with Bat-Manga" refers to a small eruption of internet chatter upon the release of Kidd's Bat-Manga!: The Secret History of Batman in Japan, a presentation of 8 Man co-creator Jiro Kuwata's '60s Batman comics in a manner that some felt downplayed Kuwata's authorship and/or the comics-as-comics in favor of a more generalist framing of the material as exotic period stuff, akin to Adam West-inspired toys and merchandise (lovingly photographed as well) - Kidd eventually responded to the criticisms with a statement of his own. A nice summary by Leigh Walton is here; I babbled here.

52:39: This should be the book cover to which Matt refers.

58:41: I swear on my immortal soul that I launched into this baffling monologue on graphic adventure games -- which were in my head anyway from studying up for my Tuesday column -- fully intending to segue into a proper discussion of 'fine' artists working in comics, but I had not seen the time, and anyway I suspect after the first minute everyone thought it'd be funny to leave the episode on a shaggy dog story involving keys and paper. The GOG sale is over, but AmerZone can still be bought; Benoît Sokal had two of his Inspector Canardo funny animal noir albums released in English in the early '90s: Shaggy Dog Story from Rijperman/Fantagraphics and Blue Angel from NBM. The same books (with the first now called Shabby Dog Story) were released in the UK by Xpresso, Fleetway's short-lived attempt to branch out into Euro-style graphic albums as an adjunct to 2000 AD; an additional Sokal short appeared in Crisis Presents #2 around the same time.

01:03:06: I love the little song outros, like we're in a radio station or something. What really happened was that Chris' wife came downstairs, having listened in for most of the show. We asked her what she thought. "Well...you went pretty hard on Chip Kidd..."

00:00: In retrospect, this sounds like some sort of haplessly self-aggrandizing mock warning about the tone of the discussion to follow -- better put the kids to bed, we got a barn burner folks -- but actually I'm just acknowledging the fact that children really are sleeping elsewhere in the Pennsylvania studios of Comic Books Are Burning In Hell, so we can't just start screaming and jumping around over the Civil War prose novel (our unexpurgated dramatization of which can be expected in your local movie theater via Fathom Events as soon as they send the contracts over). As always, I trust the humor value of a joke is directly proportional to its literalism.

00:22: Chris was actually privy to the planning of this pounding pustule of a podcast, true believer, but our eventual decision to just say fuck it and start up with these 0.whatever episodes happened so quickly we didn't immediately have a way to work him in. Episode 0.5, thus, was recorded on the night of June 10, in the basement of Chris' home, so that he and I were on one side and Tucker & Matt were on the other. The audio quality is actually pretty good, save for a few drops in the Brooklyn pickup, though we're still not officially launching; I personally think the addition of another person to the conversation stretched the topics out a little ways beyond where we'd expected, and probably encouraged a bit too much individual speaking and not enough interaction. No word from my therapist on what all of these basement locations mean, but the smart money is always on my penis (which makes grocery shopping fun).

00:40: Memories: The Collection, by Katsuhiro Otomo. Since Tucker's gonna bring it up later, the ISBN number is 0 7493 9687 3. Copies used to be kind of crazy-expensive, but they either dropped in value a bunch lately or I happened to get lucky - I snagged one for just over $20.00 after shipping. The contents are:

Sound of Sand (1979)

Hair (1979)

Electric Bird Land (1980)

Minor Swing (1977)

That's Amazing World Part I & II (1981)

Memories (1980)

Flower (1979)

Farewell to Weapons (1981)

Chronicle of the Planet Tako Part II (1982)

Chronicle of the Planet Tako (1981)

Fireball (1979)

That's Amazing World Part III & IV (1981)

All years come courtesy of this excellent French-language Otomo fansite, which identifies the book as a direct localization of Otomo Katsuhiro Anthology 1, a 1990 Japanese release, albeit with the addition of Marvel/Epic's 1992 Steve Oliff colorizations of Memories and Farewell to Weapons, which I suppose required some reorientation of the contents for technical accommodation, although I still have no idea why the Chronicle of Planet Tako sequel comes before the original. Hair, however -- a parody of Fireball -- went before its inspiration in the Japanese edition as well.

01:15: For the life of me, I still can't recall where I heard of Otomo's antipathy toward English publication of his earlier works; it's probably received wisdom passed along by superfans and publisher reps on message boards. Some of his earlier Japanese collections do appear to remain in print today, though others have vanished; in the interests of clarity, Otomo Katsuhiro Collection 1 was not a repackaging of earlier books, but apparently the start of an effort to compile Otomo's remaining short form works. A second volume was released in 1996, and has not been translated; I couldn't tell you why, save for another vague gesture in the direction of the licensor's reluctance.

01:31: I'm referring here to Yoshiharu Tsuge, one of the titans of alternative manga, and absolutely notorious for his lack of interest in foreign editions of his work. So far the entirety of his formally published oeuvre in English appears in RAW Vol. 1 #7 (Red Flowers), RAW Vol. 2 #2 (Oba's Electroplate Factory) and The Comics Journal #250 (the immortal Screw-Style), although some online translations are out there. Ego comme X also released a French-language edition of Tsuge's Munô no Hito (as L’Homme sans talent) in 2004, which Tsuge purportedly disliked (again: anecdotal).

02:20: The Memories anime actually came out in 1995. It consists of three segments: Magnetic Rose (freely adapted from the Memories manga by the late Satoshi Kon; directed by Koji Morimoto); Stink Bomb (written by Otomo and directed by Tensai Okamura, under the supervision of action maestro Yoshiaki Kawajiri; I like how I dropped fucking Wolf's Rain in there like ANYONE remembers it); and Cannon Fodder (written & directed by Otomo himself).

03:14: I'd like to formally apologize again and in writing to the nation of Germany, and the very kind German man who gave me such a good price on my book. Still, shit takes forever, this isn't the first time!

04:15: Of course, I mean the Kodansha edition of Akira Vol.1, not the Dark Horse version or anything relating to Ghost in the Shell - just settle in, this ain't the last correction today.

04:40: Specifically, for Chronicle of the Planet Tako, Otomo writes:

"Looking at it, I seem to remember that I wrote this with someone else. But as to who it was... Who drew the pictures? If they happen to read it here, would they please contact me. Well, whatever I say, they'll be annoyed. Sorry!"

That's the entire introduction. Tucker is thinking of the intro to Memories, where Otomo alludes to someone named "Takadera" who apparently drew a major splash image for the story... unless Otomo is talking about a much smaller rose image in a different splash. As the "wrote" and "drew" in the above quote indicates, the translation quality of Memories: The Collection is slightly dubious, beginning with a bit in Otomo's Introduction where he's translated as stating:

"This is my seventh collection of short stories in eight years."

and, shortly thereafter:

"Yes, I know, that's a hell of a gap between issues. Truth is, I've been working on Akira all this time, but if things had gone a little more smoothly, it would have been nice to publish some different work before beginning Akira..."

Going off the publication histories of these books -- Boogie Woogie Waltz was released in 1982, the same year Akira began serialization -- it's evident that Otomo is actually saying something to the effect of 'This is my seventh collection of short stories, and the first in eight years.' Not that I'm a brilliant editor or anything, or even that these publication dates were widely available to English speakers in '94, but it does tend to raise doubts about the whole enterprise, at least commentary-wise.

"...I decided to write about sand 'cause it's simple" is a direct quote from the intro to Sound of Sand.

05:59: If I can expand on this a little, it now occurs to me that Otomo's work does have a unifying concern: the inscrutability of vast power. Just as the poor astronauts in Sound of Sand are devoured by the very ground of an alien world, so are the yet poorer astronauts in Memories compressed by the magnetic rose into the nostalgia of the derelict spaceship: a literal pulp sci-fi threat ensconced in metaphor, 'memories' as the obliteration of everything real and current in the nostalgist's wake. Minor Swing, which Tucker later mentions, destroys its protagonist through pollution, which is represented as an endless, unstoppable river of oil. From such industrial calamities it's only a short jump to the computerized cities of Hair and Electric Bird Land, and the most perfect expression of this device: explosive psychic power a la Fireball, Domu: A Child's Dream, and Akira.

Interestingly, Otomo becomes more willing to allow the peril of such power to be challenged in his longer works, in that heroic characters eventually manifest incredible power of their own. The deranged old man of Domu is dispatched with nearly comedic ease once he's faced with his child rival on fair ground, and the youth gangs of Akira eventually cope with the collapse of their dystopian society and the release of incredible psychic force by setting up their own isolationist collective; the potential for revolution, then, embodied by Otomo's many revolutionaries, is the countervailing power that manifests in a more focused state to defeat the capriciousness of older energies.

Yet as short anime like Stink Bomb or the Otomo-written Roujin Z demonstrate, the new power can just as often function as a chaotic element, while the denizens of Cannon Fodder simply march through their endless war against an equally aged (if not imaginary) foe; more specifically politicized critiques can be found in Otomo's segments of the Robot Carnival anthology and his 2012 short comic DJ Teck * Morning Attack, where the forces of the first world raise cloyingly good-intentioned hell in Arabesque locales. Perhaps it takes a while for revolution to concentrate; in this way, Otomo's longer works perhaps analogize a sense of hope to his sad vignettes.

The depth of Farewell to Weapons, then, is in the ambiguity as to whether the drone attack is an old or new power, and the suggestion that it may not matter in such a militarized scene.

09:57: Just to illustrate, here's Oliff:

and Otomo, on the following page:

10:52: As promised (detail; the binding's tough):

11:17: Ah, what the hell:

Otomo and/or his editor helpfully note(s) in the introduction that the word balloons translate to "HAARGHH" and "GURRGK," respectively.

11:58: This is completely wrong, as evidenced above; all the stories in Memories: The Collection come from a five-year stretch from 1977-1982. I kept thinking Memories itself was made in 1990, which is the year Jason Thompson's Manga: The Complete Guide attributes it to, although it seems that was actually the year it was first collected into book form. Unless my new information is also wrong; this is the problem with not reading Japanese, you're drastically limited in your sources.

13:23: Otomo's Batman story, The Third Mask, first appeared in Batman: Black and White #4, Sept. 1996, and (obviously) appears in the various Batman: Black and White hardback and softcover collections. It has apparently been reprinted again, in some form, via Otomo's 2012 art book Kaba2.

14:32: Here's the UK edition front cover (did you like how we totally set up our cliffhanger ending?):

Matt is correct, it was originally a wraparound image; the full version can be seen here.

18:51: My comments on Otomo's relative 'mainstream' appeal in Japan are somewhat speculative, since I don't have any first or secondary sources on his work's domestic reception in the '70s. I can say, though, that we was part of a small wave with Jirô Taniguchi (another eventual Moebius cohort) and Yukinobu Hoshino (fellow traveler in pulp sci-fi kicks), or even the '60s Garo-bred Ryoichi Ikegami (who initially worked in a considerably cartoonier style) in pursuing a comparatively 'realist' visual approach that might be deemed Western - a deliberate effort in Otomo's case, at least.

Otomo did work on a few shorter serials prior to Akira (which began in '82); besides Domu, there was Sayonara Nippon (1977-78, a karate instructor in New York) and Seijaga Machini Yattekiru (1979, tales of jazz), which were presented together in the 1981 Sayonara Nippon collection. Not in English, of course!

20:07: That's 1991 for World Apartment Horror. Please consider my participation in this episode as a work of conceptual art challenging the presumption of authority in critical dialogue.

22:22: Supervillain fans will note that Mort Weisinger is the other guy in Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the Comic Book that comes off as completely horrible, although the stories just don't compare to Kane's. There's a great bit where Arnold Drake finds out that an artist is suing Kane for her anonymous work on clown paintings he'd been slinging around Hollywood, and Drake goes "He even had a ghost for the fucking clowns!"

23:25: Batman: Death by Design, by Chip Kidd & Dave Taylor. SYNOPSIS: A whole lot of major stuff is going wrong in an early 20th century design wonderland-ish Gotham, like cranes toppling over and shit, so Batman is on the case while some lady who wants Bruce Wayne to preserve a Penn Station-style historical landmark routinely gets herself into trouble. A crusading newspaper critic, a blowhard aesthete, a veritably top-hatted mustache-twirling union boss and the Joker (as: the Joker) are all involved, as is a mystery superhero(?) who might have a hidden connection to a recently-disappeared, long-disgraced architectural genius...

Did you like that? I keep feeling like we don't lay out what these comics are about before we dig into them, so I might just start putting that stuff in the show notes...

24:10: Taylor's Riddler project with Matt Wagner was 1995's Batman: Riddler - The Riddle Factory, colored by Linda Medley of the imminent Castle Waiting. Listener Michel Fiffe also draws attention to a 1999-2000 series Taylor did with writer Karl Kesel, Batman and Superman: World's Finest, where the artist was eventually joined by fellow Judge Dredd alum Peter Doherty (although Taylor didn't work on Dredd until afterward). The Alan Grant stuff I'm thinking of is a slew of Batman: Shadow of the Bat issues from '96-'97, #50-64, barring #55 and #61 (which was pencilled by Tucker Stone favorite Jim Aparo).

24:36: I feel the need to clarify that the character in question is not named "Chip Kidd," though it is obviously using Kidd as its photo reference basis.

31:22: The Journal's archives are down, and my Google cache wizardry isn't sufficient to locate the ¡Journalista! link to which Tucker refers. Anyone have it on hand?

34:14: If you'll allow it -- and of course you will, I've chloroformed you and I'm whispering into your ear, that's why you can't control the words -- I can probably offer a more sympathetic reading of Batman: Death by Design going off Matt's thought balloon comment. Because: thought balloons! Not always popular, and Kidd feels the urge to not only partake, but chow down on especially rich and cheesy variations, in which characters' most intimate, true feelings expound pregnantly above their heads, in pained silence.

You could argue, perhaps, that it's not so much what's written here as what you can see, or even feel - a pleasure of the delicious artifice itself, like sleek art deco buildings are pleasurable, like Ayn Rand superheroes are barking and smart, like old movies are textural, sensual, like how the photographs in Chip Kidd's books always seek to isolate every grain of the paper, every dot of that fine classic coloring, every nick and spot on a beat tin toy. This stuff is cool, the book says, because it's so fucking cool. Look at it! This is what I love, and here's its fictive-curatorial presentation, shorn of distracting context and dressed in only the socio-political implications you bring yourself - this is design, its function to glow inside you. Maybe this is a uniquely powerful function in superhero comics. Maybe its the very basis of superhero momentism, with the idea of cool characters and cool action transubstantiated into cool looks; not a common trick in a genre that's come to value plot over anything else.

The most immediate problem, however, with this type of reading, is that an adequate response is to say nothing more than "I've seen cooler."

40:16: That's Planetary #7. As is becoming a recurring motif in this week's notes, I can't recall where I heard Ellis relate this anecdote; it was likely on one of his message boards. Jesus, I totally shouldn't have made fun of Otomo's notes...

42:23: Matt's saying "Josh Simmons," in reference to that artist's unofficial... 'fan' comic, presently collected in The Furry Trap from Fantagraphics. Batman: Absolution was a hardcover (later softcover) graphic novel from 2002, painted by Brian Ashmore; if you were in the room with us, you'd have seen Chris' ears perk up at the very mention of J.M. DeMatteis, who wrote many favorites of his youth. "NO, WHICH ONE IS THAT?"

45:06: Before I could even sit down to write this post, an alert listener/potential Norm Breyfogle fanatic wrote in to mention that 1991's Batman: Holy Terror -- not to be confused with Frank Miller's 2011 Holy Terror, initially drawn in part as a Batman comic -- was in fact written by Alan Brennert, "actually a pretty good writer of that time period," who went down in history as the very first writer to follow... Frank Miller, on Daredevil; he later gave some assistance to Dennis O'Neil, whose own run as writer included a Matt Seneca favorite. I love it when a note comes together.

47:20: Much more about François Schuiten's & Benoît Peeters' Les Cités obscures can be found at the (French-language) Urbicande site, while Sequart's Julian Darius has been gradually updating a series overview for the English reader. I love these comics to pieces, though they've fallen into the Moebius zone of 'not enough readers on hand to justify the licensing costs, too many readers for used copies to accommodate,' resulting in high prices for NBM's mostly out-of-print English editions.

48:38: One thing I forgot to mention is that Taylor does use color in a somewhat similar way to Schuiten on one of the Les Cités books, 1987's The Tower -- if you can't find the NBM album, Dark Horse serialized the story in issues #9-14 of its Cheval Noir anthology though be warned that Schuiten does not shrink well -- where color is used sparingly as both a striking visual and a seemingly diegetic source of illumination. Granted, Schuiten does this in an 'impossible' way, so that color appears to radiate onto characters' b&w faces in furtherance of his and Peeters' themes, while Taylor adopts a more realistic approach of city lights and flame, etc., but the slight similarity is nonetheless interesting, given the architectural theme.

50:30: "[T]he whole controversy thing with Bat-Manga" refers to a small eruption of internet chatter upon the release of Kidd's Bat-Manga!: The Secret History of Batman in Japan, a presentation of 8 Man co-creator Jiro Kuwata's '60s Batman comics in a manner that some felt downplayed Kuwata's authorship and/or the comics-as-comics in favor of a more generalist framing of the material as exotic period stuff, akin to Adam West-inspired toys and merchandise (lovingly photographed as well) - Kidd eventually responded to the criticisms with a statement of his own. A nice summary by Leigh Walton is here; I babbled here.

52:39: This should be the book cover to which Matt refers.

58:41: I swear on my immortal soul that I launched into this baffling monologue on graphic adventure games -- which were in my head anyway from studying up for my Tuesday column -- fully intending to segue into a proper discussion of 'fine' artists working in comics, but I had not seen the time, and anyway I suspect after the first minute everyone thought it'd be funny to leave the episode on a shaggy dog story involving keys and paper. The GOG sale is over, but AmerZone can still be bought; Benoît Sokal had two of his Inspector Canardo funny animal noir albums released in English in the early '90s: Shaggy Dog Story from Rijperman/Fantagraphics and Blue Angel from NBM. The same books (with the first now called Shabby Dog Story) were released in the UK by Xpresso, Fleetway's short-lived attempt to branch out into Euro-style graphic albums as an adjunct to 2000 AD; an additional Sokal short appeared in Crisis Presents #2 around the same time.

01:03:06: I love the little song outros, like we're in a radio station or something. What really happened was that Chris' wife came downstairs, having listened in for most of the show. We asked her what she thought. "Well...you went pretty hard on Chip Kidd..."

<< Home