"I'm really happy that Batman is in Shonen King. Mr. Kuwata, please make it more interesting than the Batman tv show."

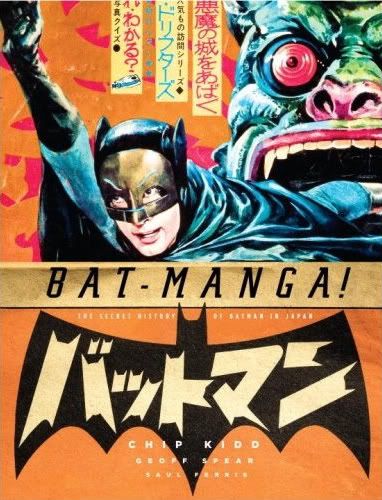

Bat-Manga! The Secret History of Batman in Japan

This is a new collection of old right-to-left comics by Jiro Kuwata. It's big (352 pages!), deluxe (glossy pages! full-color throughout!), costly-for-manga ($29.95!) and very high-profile (Pantheon!). You'll find it at any big box bookstore, although you shouldn't try and search for Kuwata's name; it's not even on the front cover. He's not the 'author' of the book - that designation is shared between designer/compiler/co-translator Chip Kidd, photographer Geoff Spear and compiler Saul Ferris, in descending order of importance, going by the font sizes.

And yet it's Kuwata -- his name tucked away on the front flap and nestled in the middle of a paragraph on the back cover -- who's the dominant presence across the book. Please don't be misled by the "secret history" language in the title; save for a context-setting Introduction, four paragraphs of Production Notes and a one-page interview with the artist, there's isn't even any text in this thing beyond the occasional illustration caption. That is, no text beyond that of Kuwata's comics, whipped up in 1966 and 1967 to feed Japan's need for Bat-fuel poured onto the raging fire of that one television show everyone had a lot of sex over, according to the historical tome authored by Robin decades later.

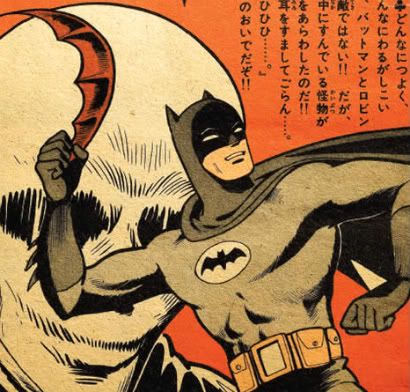

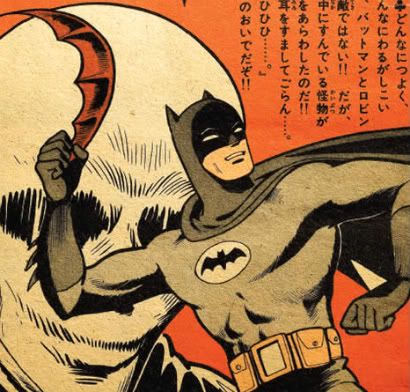

But Kuwata's work has none of the knowing camp of the television show, drawn from the oddball merriment of the proper Bat-comics of the time. The manga instead hearkens back to a somewhat earlier period, if not quite in heat-packing, neck-snapping territory; it's instead a place where a relaxed sort of seriousness hung over simple, urgent action plots. These are unabashedly basic, boyish comics, 180 degrees away from the infamously bleak Spider-Man manga Garo veteran Ryoichi Ikegami would be drawing in 1970 and 1971, a superhero fantasy so firmly planted in student protests and ethical strife it seems barely removed from the gekiga of its day. None of that for our Batman, old chums.

Interestingly, one of the writers on the Spidey manga was Kazumasa Hirai, who was also behind Kuwata's biggest hit, the 1963-65 cyborg crimefighter landmark 8 Man. The artist had never quite gotten to finishing that opus; he was arrested on weapons possession charges and briefly jailed as the final pages went into production, with fill-in artists. But Kuwata had been a pro mangaka since he was 13 years old, and his nearly two decades of accumulated skill were still marketable upon his release - I estimate the Batman assignment would have to have been among his first post-incarceration projects.

They're neat little comics, though never quite popular enough in re: Bat-mania to warrant a collected edition. Indeed, the materials as seen in this book had to be tracked down in crumbling, 40-year old back issues of the anthologies that first serialized the stuff, with each page then individually photographed in Spear's ultra-tight manner (I always picture his camera as the orbital gun from Akira), thus preserving every rip and wrinkle and marginal text declaration, not to mention all the original, inconsistent monochrome tints manga anthologies still employ today to pound a little presentational variety into weekly/monthly phonebooks of b&w comics. Often, bits of the facing page are left visible, as if urging you forward.

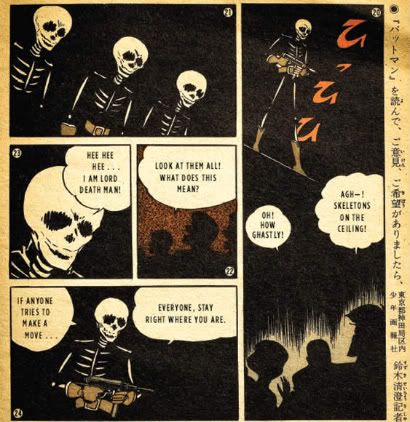

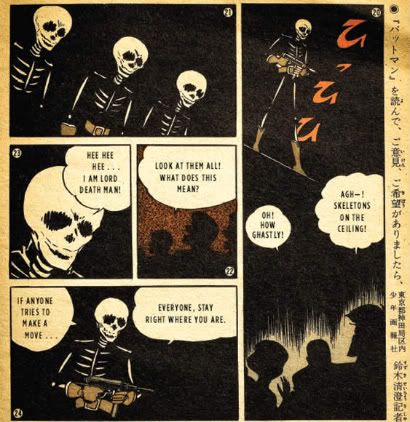

You probably won't need the extra nudge. Kuwata's comics are compulsively readable, doubtlessly benefiting from the example of Osamu Tezuka's sleek storytelling drive, a nearly omnipresent force that's left so many older manga still zipping by the contemporary reader while the stuff of Showcase Presents often seizes the eye with excess narration and thick dialogue, and a less certain command of filmic perspective. Kuwata isn't terribly focused on depth of characterization or anything -- certainly his Robin is never anything more than a prop for easy Bat-conversation or giving some villain the momentary upper hand -- but his action sequences whirl in circles with fine energy, and his visual designs carry a classy sense of menace that bolsters the disarming bluntness of his suspense narratives.

Not a lot of those narratives are complete, mind you; another side-effect of these comics' non-preservation is that chapters of individual serials are only as available as the whole goddamned phonebook they were printed in, so as a result there's only two stories in here that're actually presented in full. Yet this (necessarily) abridged state makes the characteristic Kidd/Spear supertactile format fetish presentation seem more fitting than usual, with each and every page declaring loudly that this book can only hope to be a small window into a decaying past, too far gone for anything smoother.

I wonder if these involuntary vignettes make Kuwata's plotting seem more freewheeling than it actually is; nearly every part-tale seems positioned somewhere on a simple outline of a weird villain introducing himself, Batman and Robin getting flummoxed, mayhem occurring, and Our Heroes eventually putting together uncomplicated clues to save the day. It's likely that the stories' incomplete state throws extra emphasis on their uniquely Japanese touches, like Batman staying awake for a week straight to get the work done on a really tough case, or the Batmobile running on nuclear power, or all the 'fantasy' in the work boiling down to quasi-science in the end, perhaps as a sop to manga readers' demands for 'realism,' as explained in Kuwata's interview.

Granted, this 'realism' manifests in, say, a gorilla gaining advanced human intelligence and consequently dressing in a Phantom Blot bodystocking with a white cloak to commit terrorist acts in the name of animal rights, like disrupting a showing of what appears to be a mondo movie (!!!) then blowing up the theater. Or Batman taking a dip in Clayface's body-shifting 'bioplasm' and transforming himself into a giant living Batarang so as to fling himself at the villain. Or a scientist melting his face off in a strange experiment and setting off on a crusade against anything that bears or reflects a face: clocks; gems; or even the gigantic smiling Batman head carved into the side of Mount Gotham (what, you thought they wouldn't?). As the story 'ends,' we find out it was all a ruse by a crafty thief. We never find out if Batman punches his mouth to end the story, but we can guess.

All in good fun, even as it sags a tiny bit from a latecoming attempt to explore Batman's morals via a soon-to-be-mutant urging Our Hero to kill him should he happen to develop a hunger to extinguish humankind; the choice is never in doubt, since Batman has his duty for justice, and Japan has its intermingled terror of/reliance upon advanced technology vis a vis its continuing evolution. Historical context cannot be avoided; translator Anne Ishii (with Kidd, as mentioned above) sometimes even subtitles the little fun facts that run down the sides of most pages, offering valuable education on cool stuff like castles, baseball, outer space and... um, whaling. To say nothing of the little declarations from readers (see post title) and trivia about the artist:

"Mr. Kuwata is a gun fanatic, but after seeing Out of Africa, he decided that hunting animals was wrong."

Ah, bask in those mixed signals!

What of the signals given off by the book, though? I've often declared that reprint presentations possess their own character from the way they surround the reprinted works with design and supplement and so on - but what to make of a presentation that explicitly places the compilers of the reprint materials into the seat of authorship, shuffling the artist off to parts unseen by the hands-off browser?

I mention this not to impugn the motives of Kidd, Spear and Ferris. After all, Kidd does dedicate the book to Kuwata, all of the package's sparse supplemental materials mention the circumstances of the manga's creation, and I suppose that interview didn't have to be there - hell, it's even keen enough to follow up on Kuwata's appreciation of Tezuka with a question on what he thought of Buddha, Kuwata being a devout Buddhist who's also made comics on the topic. It could be some legal obligation is floating around to keep the mangaka's name away from authorial primacy; I note with fascination that the indicia refers to the artwork as "comic book panels," isolating the images from reading sequence. I'm sure no offense is intended, and that all of the principals have only the highest respect for the work on display.

But the book we have is the book we have, and its application of authorship as coupled with unique presentational qualities creates a potent implication. In contextualizing the work in terms of the compilers/editors/photographers as authors, the book's already distanced approach -- as fascinated with the physicality of old paper as the aesthetic of the images printed upon it -- adopts the adoring-yet-aloof poise of the nostalgist. Loving photographs of period toys and illustrations separate Kuwata's comics; little context is provided. It is all a blur of novelty and sensation, to be admired as bits of time to collect, and show off.

Kuwata's pages too are shown off in this manner, so ravishing in their slow, steady return to the mush of corporeal origin. Occasionally Spear zooms into a page detail so close for illustration's sake that it seems you can stare through the page fiber backward in time to witness the page as a tree, then a sapling, then a suggestion upon a still landscape, until the Earth itself rewinds and you witness the origin of creation, which is so mind-searing that you forget it all in an instant and you're left staring at Robin's smiling face with a dizzy sensation (as happens to me every issue). Story pages are mounted with less intensity, but they are, in a way, images-as-images, among items-as-items, beyond title pages claiming presenters-as-authors, and I daresay this is not necessarily an effective means of conveying the vitality of sequential art, page-to-page, panel-to-panel.

Remember: there is hardly any text in this book that is not Kuwata's, albeit translated to English and caked with age. His comics make up maybe 80% of the thing's contents, by my very rough estimate. Yet there is a quiet urge to view his pages as if like collector's items, as doodads or memorabilia, like old things to be smiled at rather than works that might retain some of the immediacy of power that sequential works of age can still conjure from their melding of words and pictures in a profound order. Even a more charitable reading of Kuwata's pages and panels as isolated upon a rhetorical gallery wall does little to flatter the work; as already observed, the might of such manga is not in lonely page-portraits but in reading velocity. Behind glass, for all good intentions, it shrinks.

Still, I'll say again - some of the choices made in the book also carry some good sense. The pages are falling apart because they are the only pages left. The stories aren't even complete most of the time because passages are straight-up missing. It'd be error to deny the role of collectors and nostalgists in putting together many less fussy reprint projects, and it seems churlish to rake this book over the coals for making presentational choices that do respond to simple limitations of compilation, and never particularly get in the way of one's reading, if you just square your eyes on the comics, which I expect most readers will do.

It is an odd din of messages, though, focused so much on a work that's denied the pole position of subject matter fixation: it's not manga in the title but a Secret History, damned vaporous thing. Maybe that's what makes it a secret? At least Kuwata isn't hidden in the mist. It's shit that he's not up front, but know he is there; come forth, take the book in your hands and join him. You can hear different voices, but his is clear, and most compelling among options.

This is a new collection of old right-to-left comics by Jiro Kuwata. It's big (352 pages!), deluxe (glossy pages! full-color throughout!), costly-for-manga ($29.95!) and very high-profile (Pantheon!). You'll find it at any big box bookstore, although you shouldn't try and search for Kuwata's name; it's not even on the front cover. He's not the 'author' of the book - that designation is shared between designer/compiler/co-translator Chip Kidd, photographer Geoff Spear and compiler Saul Ferris, in descending order of importance, going by the font sizes.

And yet it's Kuwata -- his name tucked away on the front flap and nestled in the middle of a paragraph on the back cover -- who's the dominant presence across the book. Please don't be misled by the "secret history" language in the title; save for a context-setting Introduction, four paragraphs of Production Notes and a one-page interview with the artist, there's isn't even any text in this thing beyond the occasional illustration caption. That is, no text beyond that of Kuwata's comics, whipped up in 1966 and 1967 to feed Japan's need for Bat-fuel poured onto the raging fire of that one television show everyone had a lot of sex over, according to the historical tome authored by Robin decades later.

But Kuwata's work has none of the knowing camp of the television show, drawn from the oddball merriment of the proper Bat-comics of the time. The manga instead hearkens back to a somewhat earlier period, if not quite in heat-packing, neck-snapping territory; it's instead a place where a relaxed sort of seriousness hung over simple, urgent action plots. These are unabashedly basic, boyish comics, 180 degrees away from the infamously bleak Spider-Man manga Garo veteran Ryoichi Ikegami would be drawing in 1970 and 1971, a superhero fantasy so firmly planted in student protests and ethical strife it seems barely removed from the gekiga of its day. None of that for our Batman, old chums.

Interestingly, one of the writers on the Spidey manga was Kazumasa Hirai, who was also behind Kuwata's biggest hit, the 1963-65 cyborg crimefighter landmark 8 Man. The artist had never quite gotten to finishing that opus; he was arrested on weapons possession charges and briefly jailed as the final pages went into production, with fill-in artists. But Kuwata had been a pro mangaka since he was 13 years old, and his nearly two decades of accumulated skill were still marketable upon his release - I estimate the Batman assignment would have to have been among his first post-incarceration projects.

They're neat little comics, though never quite popular enough in re: Bat-mania to warrant a collected edition. Indeed, the materials as seen in this book had to be tracked down in crumbling, 40-year old back issues of the anthologies that first serialized the stuff, with each page then individually photographed in Spear's ultra-tight manner (I always picture his camera as the orbital gun from Akira), thus preserving every rip and wrinkle and marginal text declaration, not to mention all the original, inconsistent monochrome tints manga anthologies still employ today to pound a little presentational variety into weekly/monthly phonebooks of b&w comics. Often, bits of the facing page are left visible, as if urging you forward.

You probably won't need the extra nudge. Kuwata's comics are compulsively readable, doubtlessly benefiting from the example of Osamu Tezuka's sleek storytelling drive, a nearly omnipresent force that's left so many older manga still zipping by the contemporary reader while the stuff of Showcase Presents often seizes the eye with excess narration and thick dialogue, and a less certain command of filmic perspective. Kuwata isn't terribly focused on depth of characterization or anything -- certainly his Robin is never anything more than a prop for easy Bat-conversation or giving some villain the momentary upper hand -- but his action sequences whirl in circles with fine energy, and his visual designs carry a classy sense of menace that bolsters the disarming bluntness of his suspense narratives.

Not a lot of those narratives are complete, mind you; another side-effect of these comics' non-preservation is that chapters of individual serials are only as available as the whole goddamned phonebook they were printed in, so as a result there's only two stories in here that're actually presented in full. Yet this (necessarily) abridged state makes the characteristic Kidd/Spear supertactile format fetish presentation seem more fitting than usual, with each and every page declaring loudly that this book can only hope to be a small window into a decaying past, too far gone for anything smoother.

I wonder if these involuntary vignettes make Kuwata's plotting seem more freewheeling than it actually is; nearly every part-tale seems positioned somewhere on a simple outline of a weird villain introducing himself, Batman and Robin getting flummoxed, mayhem occurring, and Our Heroes eventually putting together uncomplicated clues to save the day. It's likely that the stories' incomplete state throws extra emphasis on their uniquely Japanese touches, like Batman staying awake for a week straight to get the work done on a really tough case, or the Batmobile running on nuclear power, or all the 'fantasy' in the work boiling down to quasi-science in the end, perhaps as a sop to manga readers' demands for 'realism,' as explained in Kuwata's interview.

Granted, this 'realism' manifests in, say, a gorilla gaining advanced human intelligence and consequently dressing in a Phantom Blot bodystocking with a white cloak to commit terrorist acts in the name of animal rights, like disrupting a showing of what appears to be a mondo movie (!!!) then blowing up the theater. Or Batman taking a dip in Clayface's body-shifting 'bioplasm' and transforming himself into a giant living Batarang so as to fling himself at the villain. Or a scientist melting his face off in a strange experiment and setting off on a crusade against anything that bears or reflects a face: clocks; gems; or even the gigantic smiling Batman head carved into the side of Mount Gotham (what, you thought they wouldn't?). As the story 'ends,' we find out it was all a ruse by a crafty thief. We never find out if Batman punches his mouth to end the story, but we can guess.

All in good fun, even as it sags a tiny bit from a latecoming attempt to explore Batman's morals via a soon-to-be-mutant urging Our Hero to kill him should he happen to develop a hunger to extinguish humankind; the choice is never in doubt, since Batman has his duty for justice, and Japan has its intermingled terror of/reliance upon advanced technology vis a vis its continuing evolution. Historical context cannot be avoided; translator Anne Ishii (with Kidd, as mentioned above) sometimes even subtitles the little fun facts that run down the sides of most pages, offering valuable education on cool stuff like castles, baseball, outer space and... um, whaling. To say nothing of the little declarations from readers (see post title) and trivia about the artist:

"Mr. Kuwata is a gun fanatic, but after seeing Out of Africa, he decided that hunting animals was wrong."

Ah, bask in those mixed signals!

What of the signals given off by the book, though? I've often declared that reprint presentations possess their own character from the way they surround the reprinted works with design and supplement and so on - but what to make of a presentation that explicitly places the compilers of the reprint materials into the seat of authorship, shuffling the artist off to parts unseen by the hands-off browser?

I mention this not to impugn the motives of Kidd, Spear and Ferris. After all, Kidd does dedicate the book to Kuwata, all of the package's sparse supplemental materials mention the circumstances of the manga's creation, and I suppose that interview didn't have to be there - hell, it's even keen enough to follow up on Kuwata's appreciation of Tezuka with a question on what he thought of Buddha, Kuwata being a devout Buddhist who's also made comics on the topic. It could be some legal obligation is floating around to keep the mangaka's name away from authorial primacy; I note with fascination that the indicia refers to the artwork as "comic book panels," isolating the images from reading sequence. I'm sure no offense is intended, and that all of the principals have only the highest respect for the work on display.

But the book we have is the book we have, and its application of authorship as coupled with unique presentational qualities creates a potent implication. In contextualizing the work in terms of the compilers/editors/photographers as authors, the book's already distanced approach -- as fascinated with the physicality of old paper as the aesthetic of the images printed upon it -- adopts the adoring-yet-aloof poise of the nostalgist. Loving photographs of period toys and illustrations separate Kuwata's comics; little context is provided. It is all a blur of novelty and sensation, to be admired as bits of time to collect, and show off.

Kuwata's pages too are shown off in this manner, so ravishing in their slow, steady return to the mush of corporeal origin. Occasionally Spear zooms into a page detail so close for illustration's sake that it seems you can stare through the page fiber backward in time to witness the page as a tree, then a sapling, then a suggestion upon a still landscape, until the Earth itself rewinds and you witness the origin of creation, which is so mind-searing that you forget it all in an instant and you're left staring at Robin's smiling face with a dizzy sensation (as happens to me every issue). Story pages are mounted with less intensity, but they are, in a way, images-as-images, among items-as-items, beyond title pages claiming presenters-as-authors, and I daresay this is not necessarily an effective means of conveying the vitality of sequential art, page-to-page, panel-to-panel.

Remember: there is hardly any text in this book that is not Kuwata's, albeit translated to English and caked with age. His comics make up maybe 80% of the thing's contents, by my very rough estimate. Yet there is a quiet urge to view his pages as if like collector's items, as doodads or memorabilia, like old things to be smiled at rather than works that might retain some of the immediacy of power that sequential works of age can still conjure from their melding of words and pictures in a profound order. Even a more charitable reading of Kuwata's pages and panels as isolated upon a rhetorical gallery wall does little to flatter the work; as already observed, the might of such manga is not in lonely page-portraits but in reading velocity. Behind glass, for all good intentions, it shrinks.

Still, I'll say again - some of the choices made in the book also carry some good sense. The pages are falling apart because they are the only pages left. The stories aren't even complete most of the time because passages are straight-up missing. It'd be error to deny the role of collectors and nostalgists in putting together many less fussy reprint projects, and it seems churlish to rake this book over the coals for making presentational choices that do respond to simple limitations of compilation, and never particularly get in the way of one's reading, if you just square your eyes on the comics, which I expect most readers will do.

It is an odd din of messages, though, focused so much on a work that's denied the pole position of subject matter fixation: it's not manga in the title but a Secret History, damned vaporous thing. Maybe that's what makes it a secret? At least Kuwata isn't hidden in the mist. It's shit that he's not up front, but know he is there; come forth, take the book in your hands and join him. You can hear different voices, but his is clear, and most compelling among options.

<< Home