Often predatory; somewhere in the grey area between a caring embrace and a flying leap to tackle someone.

GlömpX

This is a new 168-page color anthology of English-language (but mostly wordless) comics from Finland. It's limited to 1000 hardcover copies, produced by comics and music purveyor Boing Being and published by Huuda Huuda at EUR 28 or $35, although the actual U.S. price may vary; Copacetic Comics has it in stock for $39.95. I can't seem to find any other North American locations duly armed just yet, but you can import it from various sources.

The brainchild of editor Tommi Musturi -- an accomplished cartoonist whose The First Book of Hope and The Second Book of Hope are available from Belgian publisher Bries, probably at their MoCCA table in a few weeks, if you're attending -- Glömp has been ongoing at a mostly annual rate since 1997; its heart has been new work from Finnish artists, although prior issues have seen the participation of Kevin Huizenga, Anders Nilsen, Christopher Forgues, Lilli Carré, Olivier Schrauwen, Tom Gauld, Jeffrey Brown and many others. Its presence in the English-dominant world has been spotty, although earlier editions can be had through Top Shelf, Poopsheet and Quimby's (or Forbidden Planet in the UK).

This is the 10th edition of the now well-developed project, and the last to be edited by Musturi; it comes complete with a 56-minute soundtrack CD, and will be accompanied by a touring exhibition. I see a ready comparison to PictureBox's The Ganzfeld 7, which recently concluded itself with a book 'n disc all-color blowout, although other sources have drawn understandable parallels with the likewise once-modest, now-expansive Kramers Ergot. Indeed, Glömp itself deems it fit to deal with the legacy of comics anthologies in this very issue, even as it searches for somewhere new to press, maybe beyond the page.

(Janne Tervamäki)

The historical content is provided via an introductory essay by Finnish retailer Jelle Hugaerts, who briefly considers the makeup of a good comics anthology (the editor is "the soul") before launching into a history of the format, pinpointing William Gaines' affirmative pairing of stories with writers, features with features and talents with their names as the philosophical birth of the 'anthology' from the mere collection of features as was much of the Golden Age.

He then hits most of the expected American-European landmarks, although his very consideration of the European end ensures a somewhat different narrative than the North American standard; his positioning of Kramers as a sort of hybridization of the '90s-born French image fury of Le Dernier Cri with traditional narrative stands in sharp contrast to the occasional domestic characterization of American 'art' comics as freshly galloping away from accessible storytelling.

As for new advances, Hugaerts places special emphasis on minicomics and the anthology form as an arena for artists to hone and experiment, away from the growing expectation of bookshelf-ready material perilously early in an aesthetic's development (the potential of online comics goes unmentioned). "As for bigger, more book-sized anthologies, their key to success lies all the more in getting cohesive content or experimenting with the format," he notes, in what might as well be a wave to open the curtain.

Amusingly -- and speaking of cohesive content! -- the soundtrack CD seems to back this impression, with Maniacs Dream contributer Fricara Pacchu's opening track providing a long round of applause before launching into a swelling mess of sounds suggestive of an especially surreal gallery opening. The remaining three cuts (none under 10 minutes), however, exhibit more of what I'd anticipated: looping refrains and distortion studies, albeit with a certain emphasis on 'natural' base noise, exemplified by Kiiskinen's 18:17 Bill & Bull, best described as a vérité radio documentary on the subject of rubbing inflated party balloons, adapted by electromagnetic demigods for consumption in their home dimension.

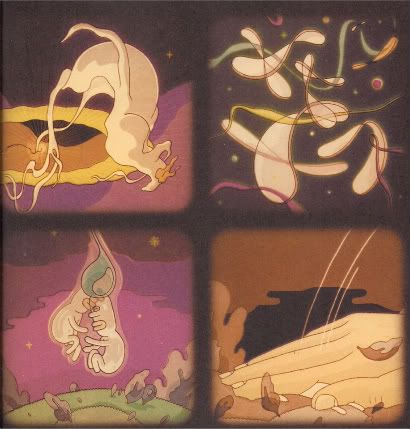

(Tommi Musturi)

There's a strong natural aspect to the comics too, perhaps inevitably so, in that this special Glömp has required all narrative pieces to be 3-D. And I don't mean computer graphics or special glasses; rather, the comics must somehow exist in three-dimensional space, beyond the flat confines of the page, yet paradoxically for the purposes of inclusion in an anthology book apart from the aforementioned live exhibition.

It's dangerous work, this, particularly headed by an essay on the development of the successful comics anthology! All those 2-D comics are marked with pencil and ink and coverings and corrections or however many digital layers, of course, but their objective is typically to reproduce on the page; that's the completed form, and the reason I find it so hard to interface with original pages hanging on a gallery wall. Even exceptions to this rule like the one-of-a-kind object transformation of Maggots can at least function in simulacrum. But comics narratives rendered as 3-D objects? How do you keep a collection of that from retreating into an exhibition catalog?

That's the big question of GlömpX, at least for me, and the solutions devised by its 15 pieces provoked some good fascination. I was really taken the book's variations in story presentation, sometimes opening a segment with a wide view of the object in question then diving in for a closer look, sometimes saving the 'full' form of the work until the end, and often mixing perspectives to compelling effect.

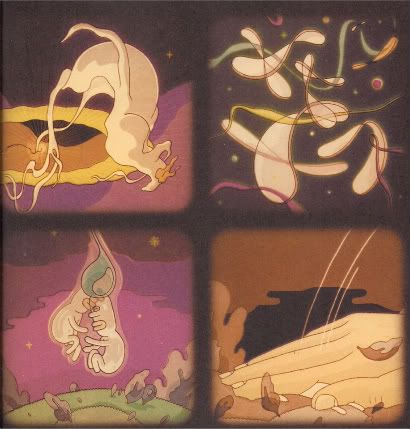

Musturi's own story/project, for example, is very simple. We're started off with a double-page photographic presentation of four sheets of painted glass standing in a lake, the glare of the sun helpfully shining through one of them. The next four pages of the book present those sheets as comics pages (see above), altered somewhat for reproduction, but nonetheless indicative of the total exhibit's intent - light shining through translucent space, illustrated on both sides, to promote a naturalistic alternative to the look of animation cels.

But while the end result is shimmering and spooky -- and appropriately themed plot-wise as a fable of elemental, godly upheaval -- the work doesn't seem benefited by its conformity to the book. All of the image is present across the pages, but it still feels excerpted, like you're missing out on not truly seeing the light shine through those plates. You're divorced, isolated from the water and the heat; behind a pane of your own.

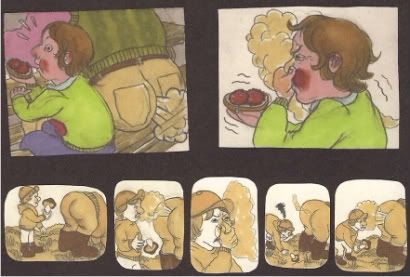

(Amanda Vähämäki; detail)

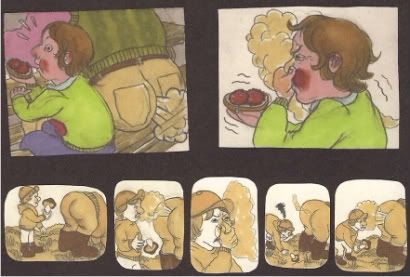

Yet even as the anthology absolutely begs the question of presentation, other pieces rise to certain innovations. Many of the stories as seen in the book are in fact augmented, in that 2-D drawings appear to be juxtaposed against careful framing of the 3-D works. There's a nice entry titled Sausages & Peas, composed by Amanda Vähämäki, whose story collection The Bun Field was recently released in North America by Drawn and Quarterly (and reviewed by Tom Spurgeon & Bart Beaty).

It's a 10-page look at a family dinner, with each left-hand page sporting 2-D studies of movement and antics by one member of the five-person clan, bordered at the top or bottom by fleeting, funny/sweet sepia memories, while each right-handed page provides an unbroken 3-D image of the entire kitchen -- seemingly formed from clay and illustrated paper/wood cut-outs -- slowly moving forward in time with each subsequent splash. In this way, Vähämäki casts her 2-D drawings as personal, subjective, while the facing 3-D content reflects the removed positioning of God, you - the reader, seeing the everything characters can't.

Nothing happens in the story, by the way, but it's astonishing how the artist's give-and-take between subjectivity and objectivity, involvement and dispassion, creates its own emotional power. It completely transforms the disability of Musturi's piece -- or, say, the inverted presentation of Pauliina Mäkelä's Hexen, a lineup of alternating fox and child images ultimately revealed to be taken from the top of a cloth draped around a doll, like the solution at the end of a mystery -- into a meaningful aspect of the reader's involvement with the work.

(Jyrki Heikkinen; detail)

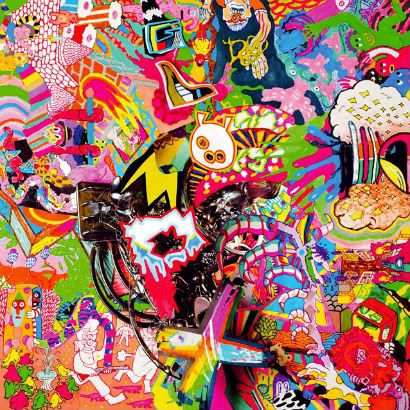

Other contributions offer different compositions. Kramers Ergot 7 veteran Aapo Rapi teams with textile artist and weaver Sonja Salomäki for Disco Pizza, a dizzy burst of one medium after another, paintings running into models heading towards photography preceding sickly-colored comics, all this company in service of two characters' shared lonliness.

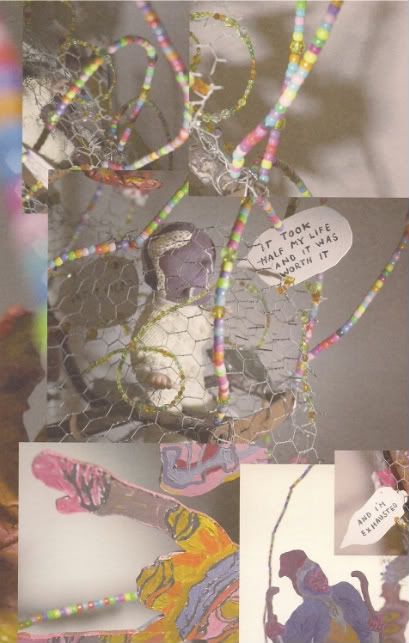

Elsewhere, Katri Sipiläinen presses deeper into contrast, pitting a full-bore Leisure Town-style sculpture fumetti against a b&w pencil story as baleful sagas of personal insecurity on two sides of a fantasy lake. Some pieces even blur the line of what's what, like Janne Tervamäki's Strange Weather, a near-abstract interplay of one-panel cartoons and searing illustrational details that effectively obscures any trace of the 3-D element, maybe as a means of begging the question of its utility.

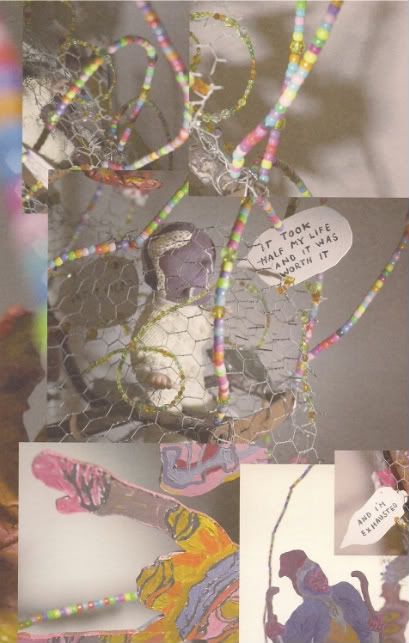

My favorite pieces, though, find similar means of deconstructing and reconstructing the very stuff of the comics page. Witness above a little taste of Jyrki Heikkinen's Hip Hip Hooray!, a tall sculpture depicting the path of various characters toward the experience of death, floating word balloons built right in. Three double-page photographic splashes showcase portions of the whole, but they're pasted over with smaller images zooming in on different characters, thus creating 'panels' laid out to create the illusion of characters moving along the road, reasserting the primacy of the 2-D page as a means of traversing a 3-D setting.

Meanwhile, Le Dernier Cri participant Reijo Kärkkäinen slices out a garish diorama for The Operator, all blurry focus and jarring shapes at first, then moving in to place 'panels' cut from elsewhere on set in almost exactly the same jagged, clashing angles as the contours of the set itself, resulting in a rather profound disruption of reality through just-impossible-enough perspectives, mutating the 3-D environment itself by mimicking its qualities in a 2-D modification. It's like a drive through the uncanny valley, except now you're checking out the scenery rather than the inhabitants - a novel means of provoking environmental dread, which naturally rises to the forefront of the narrative, through its violation of nature.

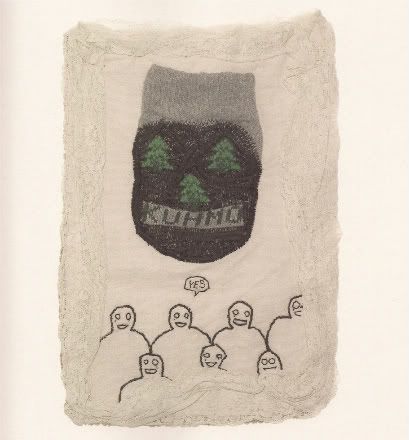

(Hanneriina Moisseinen)

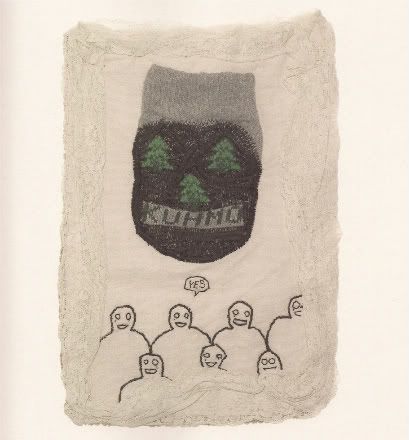

I can't say every part of this book is so complex, or nearly as involved; that's the toll of the anthology. Some will find Hanneriina Moisseinen's tale of heavy metal triumph via embroidered doilies to be overly precious, although others (like myself) might be charmed. Moreover, I readily admit that some might find the very concept limiting - these are not 'literary' comics by the North American understanding, though they are narratives, which certain readers may well deem shallow if they consider the presentational tension at work to be less than compelling.

Still, I can't help but feel impressed with this book, even while I'm unimpressed with some of its parts. Potentially a leaden piece of a multimedia puzzle, it's instead a good-natured harassment of the anthology comic, determined to strike a few worthwhile balances between the flat necessities of the page and the horizon looming behind. I don't know if it exposes a vital new dimension in the comics form, as departing editor Musturi would wish, but it supplies ample suggestion that the anthologies to follow don't have to move along the studied line of history; there are other directions, even if travelled by a leap from behind and a doubling up.

This is a new 168-page color anthology of English-language (but mostly wordless) comics from Finland. It's limited to 1000 hardcover copies, produced by comics and music purveyor Boing Being and published by Huuda Huuda at EUR 28 or $35, although the actual U.S. price may vary; Copacetic Comics has it in stock for $39.95. I can't seem to find any other North American locations duly armed just yet, but you can import it from various sources.

The brainchild of editor Tommi Musturi -- an accomplished cartoonist whose The First Book of Hope and The Second Book of Hope are available from Belgian publisher Bries, probably at their MoCCA table in a few weeks, if you're attending -- Glömp has been ongoing at a mostly annual rate since 1997; its heart has been new work from Finnish artists, although prior issues have seen the participation of Kevin Huizenga, Anders Nilsen, Christopher Forgues, Lilli Carré, Olivier Schrauwen, Tom Gauld, Jeffrey Brown and many others. Its presence in the English-dominant world has been spotty, although earlier editions can be had through Top Shelf, Poopsheet and Quimby's (or Forbidden Planet in the UK).

This is the 10th edition of the now well-developed project, and the last to be edited by Musturi; it comes complete with a 56-minute soundtrack CD, and will be accompanied by a touring exhibition. I see a ready comparison to PictureBox's The Ganzfeld 7, which recently concluded itself with a book 'n disc all-color blowout, although other sources have drawn understandable parallels with the likewise once-modest, now-expansive Kramers Ergot. Indeed, Glömp itself deems it fit to deal with the legacy of comics anthologies in this very issue, even as it searches for somewhere new to press, maybe beyond the page.

(Janne Tervamäki)

The historical content is provided via an introductory essay by Finnish retailer Jelle Hugaerts, who briefly considers the makeup of a good comics anthology (the editor is "the soul") before launching into a history of the format, pinpointing William Gaines' affirmative pairing of stories with writers, features with features and talents with their names as the philosophical birth of the 'anthology' from the mere collection of features as was much of the Golden Age.

He then hits most of the expected American-European landmarks, although his very consideration of the European end ensures a somewhat different narrative than the North American standard; his positioning of Kramers as a sort of hybridization of the '90s-born French image fury of Le Dernier Cri with traditional narrative stands in sharp contrast to the occasional domestic characterization of American 'art' comics as freshly galloping away from accessible storytelling.

As for new advances, Hugaerts places special emphasis on minicomics and the anthology form as an arena for artists to hone and experiment, away from the growing expectation of bookshelf-ready material perilously early in an aesthetic's development (the potential of online comics goes unmentioned). "As for bigger, more book-sized anthologies, their key to success lies all the more in getting cohesive content or experimenting with the format," he notes, in what might as well be a wave to open the curtain.

Amusingly -- and speaking of cohesive content! -- the soundtrack CD seems to back this impression, with Maniacs Dream contributer Fricara Pacchu's opening track providing a long round of applause before launching into a swelling mess of sounds suggestive of an especially surreal gallery opening. The remaining three cuts (none under 10 minutes), however, exhibit more of what I'd anticipated: looping refrains and distortion studies, albeit with a certain emphasis on 'natural' base noise, exemplified by Kiiskinen's 18:17 Bill & Bull, best described as a vérité radio documentary on the subject of rubbing inflated party balloons, adapted by electromagnetic demigods for consumption in their home dimension.

(Tommi Musturi)

There's a strong natural aspect to the comics too, perhaps inevitably so, in that this special Glömp has required all narrative pieces to be 3-D. And I don't mean computer graphics or special glasses; rather, the comics must somehow exist in three-dimensional space, beyond the flat confines of the page, yet paradoxically for the purposes of inclusion in an anthology book apart from the aforementioned live exhibition.

It's dangerous work, this, particularly headed by an essay on the development of the successful comics anthology! All those 2-D comics are marked with pencil and ink and coverings and corrections or however many digital layers, of course, but their objective is typically to reproduce on the page; that's the completed form, and the reason I find it so hard to interface with original pages hanging on a gallery wall. Even exceptions to this rule like the one-of-a-kind object transformation of Maggots can at least function in simulacrum. But comics narratives rendered as 3-D objects? How do you keep a collection of that from retreating into an exhibition catalog?

That's the big question of GlömpX, at least for me, and the solutions devised by its 15 pieces provoked some good fascination. I was really taken the book's variations in story presentation, sometimes opening a segment with a wide view of the object in question then diving in for a closer look, sometimes saving the 'full' form of the work until the end, and often mixing perspectives to compelling effect.

Musturi's own story/project, for example, is very simple. We're started off with a double-page photographic presentation of four sheets of painted glass standing in a lake, the glare of the sun helpfully shining through one of them. The next four pages of the book present those sheets as comics pages (see above), altered somewhat for reproduction, but nonetheless indicative of the total exhibit's intent - light shining through translucent space, illustrated on both sides, to promote a naturalistic alternative to the look of animation cels.

But while the end result is shimmering and spooky -- and appropriately themed plot-wise as a fable of elemental, godly upheaval -- the work doesn't seem benefited by its conformity to the book. All of the image is present across the pages, but it still feels excerpted, like you're missing out on not truly seeing the light shine through those plates. You're divorced, isolated from the water and the heat; behind a pane of your own.

(Amanda Vähämäki; detail)

Yet even as the anthology absolutely begs the question of presentation, other pieces rise to certain innovations. Many of the stories as seen in the book are in fact augmented, in that 2-D drawings appear to be juxtaposed against careful framing of the 3-D works. There's a nice entry titled Sausages & Peas, composed by Amanda Vähämäki, whose story collection The Bun Field was recently released in North America by Drawn and Quarterly (and reviewed by Tom Spurgeon & Bart Beaty).

It's a 10-page look at a family dinner, with each left-hand page sporting 2-D studies of movement and antics by one member of the five-person clan, bordered at the top or bottom by fleeting, funny/sweet sepia memories, while each right-handed page provides an unbroken 3-D image of the entire kitchen -- seemingly formed from clay and illustrated paper/wood cut-outs -- slowly moving forward in time with each subsequent splash. In this way, Vähämäki casts her 2-D drawings as personal, subjective, while the facing 3-D content reflects the removed positioning of God, you - the reader, seeing the everything characters can't.

Nothing happens in the story, by the way, but it's astonishing how the artist's give-and-take between subjectivity and objectivity, involvement and dispassion, creates its own emotional power. It completely transforms the disability of Musturi's piece -- or, say, the inverted presentation of Pauliina Mäkelä's Hexen, a lineup of alternating fox and child images ultimately revealed to be taken from the top of a cloth draped around a doll, like the solution at the end of a mystery -- into a meaningful aspect of the reader's involvement with the work.

(Jyrki Heikkinen; detail)

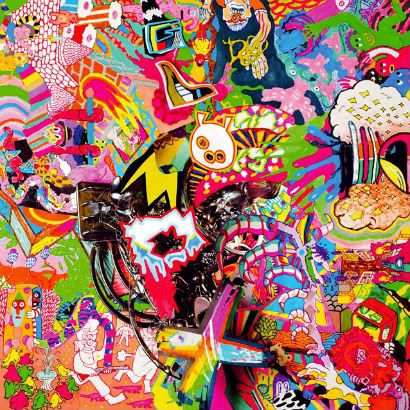

Other contributions offer different compositions. Kramers Ergot 7 veteran Aapo Rapi teams with textile artist and weaver Sonja Salomäki for Disco Pizza, a dizzy burst of one medium after another, paintings running into models heading towards photography preceding sickly-colored comics, all this company in service of two characters' shared lonliness.

Elsewhere, Katri Sipiläinen presses deeper into contrast, pitting a full-bore Leisure Town-style sculpture fumetti against a b&w pencil story as baleful sagas of personal insecurity on two sides of a fantasy lake. Some pieces even blur the line of what's what, like Janne Tervamäki's Strange Weather, a near-abstract interplay of one-panel cartoons and searing illustrational details that effectively obscures any trace of the 3-D element, maybe as a means of begging the question of its utility.

My favorite pieces, though, find similar means of deconstructing and reconstructing the very stuff of the comics page. Witness above a little taste of Jyrki Heikkinen's Hip Hip Hooray!, a tall sculpture depicting the path of various characters toward the experience of death, floating word balloons built right in. Three double-page photographic splashes showcase portions of the whole, but they're pasted over with smaller images zooming in on different characters, thus creating 'panels' laid out to create the illusion of characters moving along the road, reasserting the primacy of the 2-D page as a means of traversing a 3-D setting.

Meanwhile, Le Dernier Cri participant Reijo Kärkkäinen slices out a garish diorama for The Operator, all blurry focus and jarring shapes at first, then moving in to place 'panels' cut from elsewhere on set in almost exactly the same jagged, clashing angles as the contours of the set itself, resulting in a rather profound disruption of reality through just-impossible-enough perspectives, mutating the 3-D environment itself by mimicking its qualities in a 2-D modification. It's like a drive through the uncanny valley, except now you're checking out the scenery rather than the inhabitants - a novel means of provoking environmental dread, which naturally rises to the forefront of the narrative, through its violation of nature.

(Hanneriina Moisseinen)

I can't say every part of this book is so complex, or nearly as involved; that's the toll of the anthology. Some will find Hanneriina Moisseinen's tale of heavy metal triumph via embroidered doilies to be overly precious, although others (like myself) might be charmed. Moreover, I readily admit that some might find the very concept limiting - these are not 'literary' comics by the North American understanding, though they are narratives, which certain readers may well deem shallow if they consider the presentational tension at work to be less than compelling.

Still, I can't help but feel impressed with this book, even while I'm unimpressed with some of its parts. Potentially a leaden piece of a multimedia puzzle, it's instead a good-natured harassment of the anthology comic, determined to strike a few worthwhile balances between the flat necessities of the page and the horizon looming behind. I don't know if it exposes a vital new dimension in the comics form, as departing editor Musturi would wish, but it supplies ample suggestion that the anthologies to follow don't have to move along the studied line of history; there are other directions, even if travelled by a leap from behind and a doubling up.

<< Home