"It's just another one of life's strange mysteries, I guess; as strange in its own way as that odd old song."

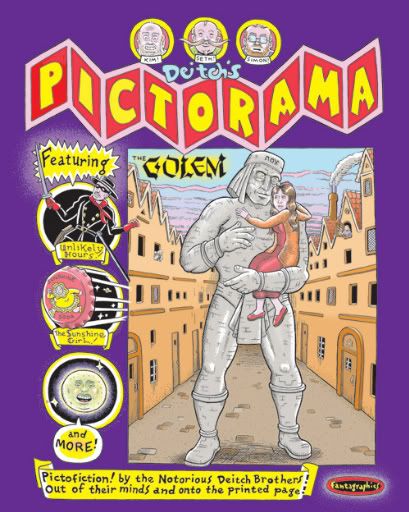

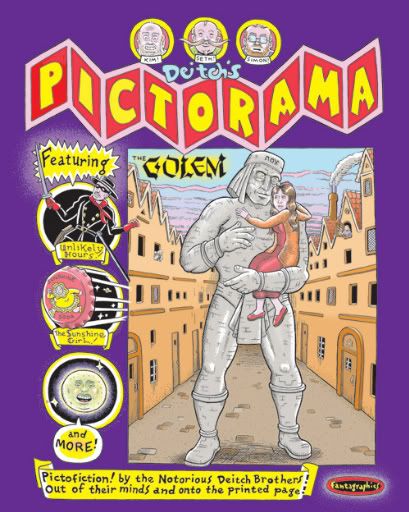

Deitch's Pictorama

This is a squat, squarebound softcover that Fantagraphics put out a few weeks ago, a 200-page, $18.99 collection of new stuff by a whole family of comics-attuned artists. It even slipped out from Diamond on the very same day as the publisher's similarly-packaged (and much higher-profile) relaunch of Love and Rockets.

I can't say I'm surprised to have heard little about it since; setting aside matters of simple proximity of release -- not to mention the general clot of stuff choked out onto fine North American comics store shelves each and every Wednesday -- the Deitch brothers simply don't have the name recognition of the younger Hernandez crew. Nor do they all work in comics. Nor are they even working in comics here.

No, Deitch's Pictorama (possessive in the singular, implicitly familial) is a collection of five illustrated prose stories that have somehow gotten themselves dubbed "Pictofiction," a label that eldest brother, '60s underground veteran and project head Kim Deitch happily identifies as copped from post-Code EC Comics magazines, which had absolutely nothing to do with what you'll find here; Deitch instead proffers the project via Foreword as like pulp magazines ("but with a lot more pictures") and in the tradition of the Victorian illustrated novels -- think Vanity Fair, which was originally stuffed with Thackeray's own artwork -- that he sees as precursors to the "graphic novel" (his words). To wit:

"What I think is beginning to happen in this book is exactly what I hoped would happen, which is, perhaps it would begin to contribute toward a hybrid medium for graphic novels, better merging the written fiction and comics mediums. I chose my words carefully in that last sentence for good reason. I'm not so conceited as to suggest that this is something that I'm doing all by myself."

Do note the equivocating language of "beginning to," which is vital; all terminology aside, these are, fundamentally, illustrated prose stories by what I expect will be most readers' latent standard of what an 'illustrated prose story' might look like, albeit with the addition of the occasional word balloon or caption-ensconced narrative aside, or maybe a few words captured inside an illustration itself for special emphasis. And that's mostly Kim's stuff.

Indeed, Kim's two included solo works will be familiar to anyone who's read the introductory bits of Boulevard of Broken Dreams; the other three entries are even less complex than that. The project doesn't even go as far as Fantagraphics' last foray into illustrated prose, Leah Hayes' scratchboard-based Funeral of the Heart, which made some attempt to apportion its handwritten language so as to draw power from particular images or simple yawning black space.

Here, the text primarily continues unabated, sandwiching or brushing against images that set particular scenes or visualize specific activities, and occasionally pouring over boxes of specialized information (say, a scene depicting a recording session, its own dialogue and inset captions offering pertinent background). But mostly the illustrations are purely illustrative, leaving the reader to wonder if they're being 'put on' a bit in a marketing sense, or if maybe the experiment is at such an early stage that it's grasping at innovation through sheer proliferation - there are a lot of pictures in here, mind you.

Still, I suspect this lack of declared (or maybe just hinted at) originality probably won't deter many of Kim Deitch's readers. His work is an acquired taste, for sure, but once you've got it you become a bit like one of the lunatics of archaic pop culture that fill his playful histories, folks privy to amusements that function as gateways to mad, secret histories. His is the most expansively adorned vision of all the 'underground' comics artists, encompassing generation-spanning historical fictions, sprawling faux-autobiographical tall tales and short, baroque fancies alike; it's an aesthetic that didn't quite flower until after the underground era was over, and even then never really had a complimentary venue until the rise of bookshelf-ready fat comics, however you want to title them.

He's also not an artist that excerpts well: his plasticine characters and model-like environments seem stiffly posed under even the best of circumstances, only accumulating significant power through the build of his stories. But that's the trick of comics, isn't it - pictures and words? The accumulating showbiz vignettes of Shadowland and the increasingly frenzied collector's inquiries of Alias the Cat manage to cohere Deitch's visual approach into something truly fitting, a flattened landscape of pliable-looking bodies and and grinning, busy decoration, in which everyone are collectible toys on a stage, one that can be whisked away and substituted for something odder at a moment's notice.

His is a bendable reality, but not infinitely so: the stuff of old entertainment -- cartoons, comics, silent movies, jazz records, dolls -- is gifted with the exclusive power to reveal how people truly lived, in ways that usually defy straight notions of logic or realism. No wonder folks always go insane in these things!

And no wonder Deitch might want to mess around with his storytelling approach, given how well recent format developments have treated him. He's also what I like to call an 'in-panel' artist - the kind of cartoonist that divines much of his or her power from how fixed images react with the story being told in an individual panel, as opposed to someone that particularly thrives on layouts or panel-to-panel flow. That's not at all popular outlook vis-a-vis today's art-focused critical discourse (which prizes comprehensive usage of formal attributes), and it's actually led Deitch to label himself less a comics artist than "a writer who draws," but it does facilitate a very smooth transition to the illustrated prose form, especially with as many illustrations as Deitch provides. Tellingly, the artist has announced no forthcoming comics works beyond a Kramers Ergot 7 contribution, with his next 'big' project planned to be a full-blown illustrated prose novel, with maybe a second volume of this project released in the interim.

None of this is to say that there aren't obvious differences in approach between this book's artists, or even Kim Deitch's work in collaboration with those other artists. Take middle child Simon Deitch:

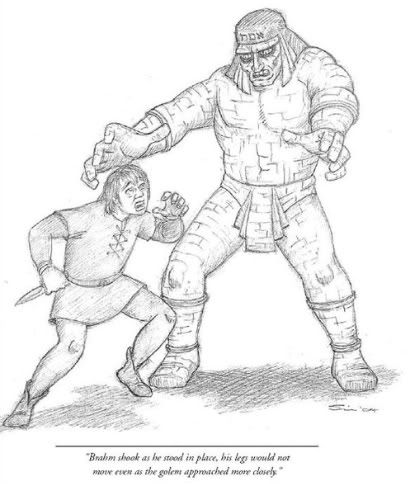

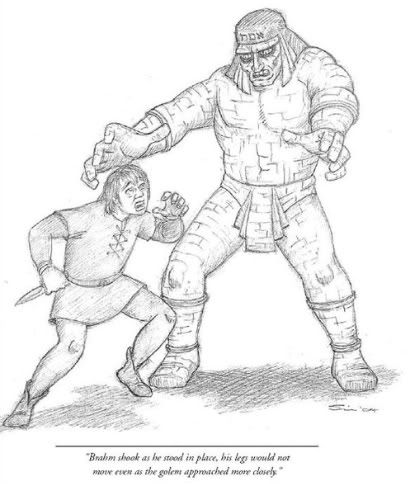

Simon was also an underground-era cartoonist, if far less prolific than Kim, and is probably best known as co-writer/contributing designer to Boulevard of Broken Dreams and co-creator/sometimes artist of the Southern Fried Fugitives feature in Nickelodeon Magazine (he's also worked in television animation on Nick's Doug and MTV's Beavis and Butt-Head). He illustrates one story in here, The Golem, which he also conceived, although youngest brother Seth provides the text.

One thing that really struck me going through that 166-page Deitch family mass interview in The Comics Journal (#292, Oct. 2008) was the repeated notion that Simon always seemed to exhibit more sheer artistic talent, while Kim sort of hashed out a place and a style to accommodate his limitations. Sez father Gene Deitch: "Kim's stuff is not ugly but, as I say, he is a fascinating naïvist and a decorative artist.... He's a primitive as far as art, but he's highly sophisticated in the way he uses this."

And sure enough, while Simon's drawings for The Golem are more technically sound in terms of anatomy and perspective and such -- not to mention nicely tactile when dealing with clothing or architecture -- they're also distanced, set away from Seth's text and given individual captions; they're presented in a formal manner that doesn't flatter their pencilled forms, leaving the story feeling incomplete before you even get into actual plot, a semi-epistolary thing concerning a rote 'he who tampered in God's domain' scenario, complete with a driven inventor, a pure maiden and a doomed, romantic monster.

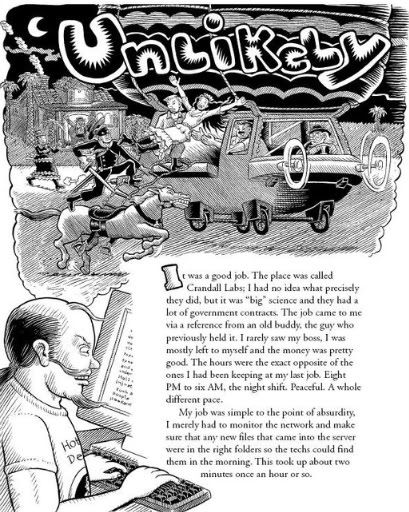

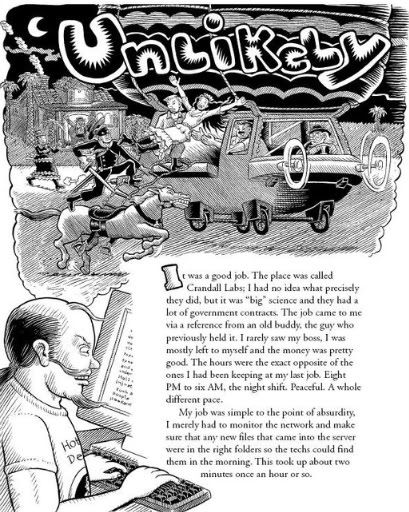

Compare that to Kim's primary collaboration with Seth, Unlikely Hours:

All of Seth's three stories in here (and for the record, they go Kim-Kim, Seth-Simon, Seth-Kim, Seth-Kim and Kim-Kim) are presented in a standardized font, as opposed to Kim's handwriting in his solo works; Seth did produce comics-informed collage work in a 1983-91 zine called Get Stupid, but he's primarily done writing in sources like Chris Ware's The Rag Time Ephemeralist, so the word processor feeling of his text marks his presence in the book.

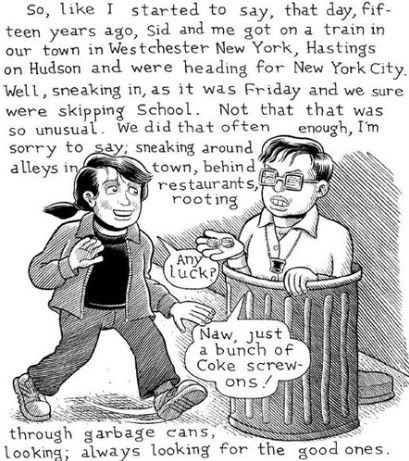

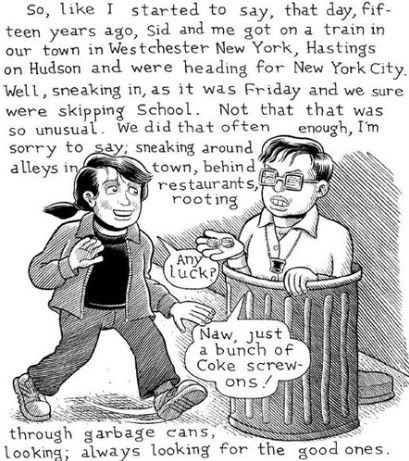

Still, notice how Kim's art surrounds the text, trapping it in a cloud of white that seems to emanate from that keyboard, a secondary imagining beneath the more obvious fantasy up top. I'm not sure how collaborative the arrangements were, but Kim's art is consistently active, bumping text around and slicing sentences in half and catching paragraphs in the steam rising from coffee. Sure, there doesn't always seem to be logic behind some of these choices -- the steam-catching bit manages to grab some of a preceding scene at a different location, for example -- nor does any of it strike me as terribly innovative a melding of the prose and comics forms, but it does impose Kim's 'flavor' onto Seth's text in a way that Simon's detached work does not.

And if Kim's illustrations have anything it's powerful personality. Unlikely Hours becomes infused with the same tall tale sensibility that marks a lot of Kim's solo works, even though Seth is a less propulsive writer, and his story of a guy working night shift at a lab and becoming convinced that the local dumpster rats are 'planning something' doesn't hang together with the same crackpot logic. The difference is palpable in Children of Aruf, wherein Kim only provides a lone full-page illustration, leaving Seth to meander through a selected tour of a world in which dogs can speak like humans. It's vaguely touching in the sheer empathy it brings to the subject, but Seth's language doesn't bring a lot to the telling.

No, the most striking stuff in here is surely courtesy of Kim Deitch alone. The shorter of the two, The Cop on the Beat, the Man in the Moon and Me, is Deitchian to the point of feeling like a yarn is being spun right in front of you with little concern for pace, perfectly willing to toss in an extended digression into big band and jazz musicians while recounting a typically beyond-plausible story of the artist's love of old cartoons and how it bumped into some of his experiences while working on comics in NYC in the '60s.

The Sunshine Girl is longer -- actually the longest story in the book -- and most perfectly Kim Deitch. It's a takeoff of Deitch's work as a cartoonist-journalist for Details (it was odd seeing an execution covered in his distinct style), in which he relays the story of a young woman who's intimately connected to the world of bottle cap collecting. Being a Deitch tale, just enough oddball truth is present to set the stage for a century-spanning opus centered around a counterculture entrepreneur's swingin' '60s plan to license Deitch's (actual) Sunshine Girl character from the East Village Other for a line of LSD-infused soft drinks inspired by the (actual) presence of cocaine in Coca-Cola for the first 15+ years of its existence, a calamity that has great repercussions on Our Narrator, who came of age amidst the crown cap scene of the early '90s, something about to explode into a commercial boom (hmmm, what's that like?) that belies the profound spiritual revelations that both ruined the girl's family and might yet provide for a lasting solace.

Collectors, madmen, marginal histories, forgotten distractions, profundity-through-jest: that's Kim Deitch, ace bullshit reporter no matter how he's filing his stories. I don't know how it'll look in coming years, but I'm glad it's still coming.

This is a squat, squarebound softcover that Fantagraphics put out a few weeks ago, a 200-page, $18.99 collection of new stuff by a whole family of comics-attuned artists. It even slipped out from Diamond on the very same day as the publisher's similarly-packaged (and much higher-profile) relaunch of Love and Rockets.

I can't say I'm surprised to have heard little about it since; setting aside matters of simple proximity of release -- not to mention the general clot of stuff choked out onto fine North American comics store shelves each and every Wednesday -- the Deitch brothers simply don't have the name recognition of the younger Hernandez crew. Nor do they all work in comics. Nor are they even working in comics here.

No, Deitch's Pictorama (possessive in the singular, implicitly familial) is a collection of five illustrated prose stories that have somehow gotten themselves dubbed "Pictofiction," a label that eldest brother, '60s underground veteran and project head Kim Deitch happily identifies as copped from post-Code EC Comics magazines, which had absolutely nothing to do with what you'll find here; Deitch instead proffers the project via Foreword as like pulp magazines ("but with a lot more pictures") and in the tradition of the Victorian illustrated novels -- think Vanity Fair, which was originally stuffed with Thackeray's own artwork -- that he sees as precursors to the "graphic novel" (his words). To wit:

"What I think is beginning to happen in this book is exactly what I hoped would happen, which is, perhaps it would begin to contribute toward a hybrid medium for graphic novels, better merging the written fiction and comics mediums. I chose my words carefully in that last sentence for good reason. I'm not so conceited as to suggest that this is something that I'm doing all by myself."

Do note the equivocating language of "beginning to," which is vital; all terminology aside, these are, fundamentally, illustrated prose stories by what I expect will be most readers' latent standard of what an 'illustrated prose story' might look like, albeit with the addition of the occasional word balloon or caption-ensconced narrative aside, or maybe a few words captured inside an illustration itself for special emphasis. And that's mostly Kim's stuff.

Indeed, Kim's two included solo works will be familiar to anyone who's read the introductory bits of Boulevard of Broken Dreams; the other three entries are even less complex than that. The project doesn't even go as far as Fantagraphics' last foray into illustrated prose, Leah Hayes' scratchboard-based Funeral of the Heart, which made some attempt to apportion its handwritten language so as to draw power from particular images or simple yawning black space.

Here, the text primarily continues unabated, sandwiching or brushing against images that set particular scenes or visualize specific activities, and occasionally pouring over boxes of specialized information (say, a scene depicting a recording session, its own dialogue and inset captions offering pertinent background). But mostly the illustrations are purely illustrative, leaving the reader to wonder if they're being 'put on' a bit in a marketing sense, or if maybe the experiment is at such an early stage that it's grasping at innovation through sheer proliferation - there are a lot of pictures in here, mind you.

Still, I suspect this lack of declared (or maybe just hinted at) originality probably won't deter many of Kim Deitch's readers. His work is an acquired taste, for sure, but once you've got it you become a bit like one of the lunatics of archaic pop culture that fill his playful histories, folks privy to amusements that function as gateways to mad, secret histories. His is the most expansively adorned vision of all the 'underground' comics artists, encompassing generation-spanning historical fictions, sprawling faux-autobiographical tall tales and short, baroque fancies alike; it's an aesthetic that didn't quite flower until after the underground era was over, and even then never really had a complimentary venue until the rise of bookshelf-ready fat comics, however you want to title them.

He's also not an artist that excerpts well: his plasticine characters and model-like environments seem stiffly posed under even the best of circumstances, only accumulating significant power through the build of his stories. But that's the trick of comics, isn't it - pictures and words? The accumulating showbiz vignettes of Shadowland and the increasingly frenzied collector's inquiries of Alias the Cat manage to cohere Deitch's visual approach into something truly fitting, a flattened landscape of pliable-looking bodies and and grinning, busy decoration, in which everyone are collectible toys on a stage, one that can be whisked away and substituted for something odder at a moment's notice.

His is a bendable reality, but not infinitely so: the stuff of old entertainment -- cartoons, comics, silent movies, jazz records, dolls -- is gifted with the exclusive power to reveal how people truly lived, in ways that usually defy straight notions of logic or realism. No wonder folks always go insane in these things!

And no wonder Deitch might want to mess around with his storytelling approach, given how well recent format developments have treated him. He's also what I like to call an 'in-panel' artist - the kind of cartoonist that divines much of his or her power from how fixed images react with the story being told in an individual panel, as opposed to someone that particularly thrives on layouts or panel-to-panel flow. That's not at all popular outlook vis-a-vis today's art-focused critical discourse (which prizes comprehensive usage of formal attributes), and it's actually led Deitch to label himself less a comics artist than "a writer who draws," but it does facilitate a very smooth transition to the illustrated prose form, especially with as many illustrations as Deitch provides. Tellingly, the artist has announced no forthcoming comics works beyond a Kramers Ergot 7 contribution, with his next 'big' project planned to be a full-blown illustrated prose novel, with maybe a second volume of this project released in the interim.

None of this is to say that there aren't obvious differences in approach between this book's artists, or even Kim Deitch's work in collaboration with those other artists. Take middle child Simon Deitch:

Simon was also an underground-era cartoonist, if far less prolific than Kim, and is probably best known as co-writer/contributing designer to Boulevard of Broken Dreams and co-creator/sometimes artist of the Southern Fried Fugitives feature in Nickelodeon Magazine (he's also worked in television animation on Nick's Doug and MTV's Beavis and Butt-Head). He illustrates one story in here, The Golem, which he also conceived, although youngest brother Seth provides the text.

One thing that really struck me going through that 166-page Deitch family mass interview in The Comics Journal (#292, Oct. 2008) was the repeated notion that Simon always seemed to exhibit more sheer artistic talent, while Kim sort of hashed out a place and a style to accommodate his limitations. Sez father Gene Deitch: "Kim's stuff is not ugly but, as I say, he is a fascinating naïvist and a decorative artist.... He's a primitive as far as art, but he's highly sophisticated in the way he uses this."

And sure enough, while Simon's drawings for The Golem are more technically sound in terms of anatomy and perspective and such -- not to mention nicely tactile when dealing with clothing or architecture -- they're also distanced, set away from Seth's text and given individual captions; they're presented in a formal manner that doesn't flatter their pencilled forms, leaving the story feeling incomplete before you even get into actual plot, a semi-epistolary thing concerning a rote 'he who tampered in God's domain' scenario, complete with a driven inventor, a pure maiden and a doomed, romantic monster.

Compare that to Kim's primary collaboration with Seth, Unlikely Hours:

All of Seth's three stories in here (and for the record, they go Kim-Kim, Seth-Simon, Seth-Kim, Seth-Kim and Kim-Kim) are presented in a standardized font, as opposed to Kim's handwriting in his solo works; Seth did produce comics-informed collage work in a 1983-91 zine called Get Stupid, but he's primarily done writing in sources like Chris Ware's The Rag Time Ephemeralist, so the word processor feeling of his text marks his presence in the book.

Still, notice how Kim's art surrounds the text, trapping it in a cloud of white that seems to emanate from that keyboard, a secondary imagining beneath the more obvious fantasy up top. I'm not sure how collaborative the arrangements were, but Kim's art is consistently active, bumping text around and slicing sentences in half and catching paragraphs in the steam rising from coffee. Sure, there doesn't always seem to be logic behind some of these choices -- the steam-catching bit manages to grab some of a preceding scene at a different location, for example -- nor does any of it strike me as terribly innovative a melding of the prose and comics forms, but it does impose Kim's 'flavor' onto Seth's text in a way that Simon's detached work does not.

And if Kim's illustrations have anything it's powerful personality. Unlikely Hours becomes infused with the same tall tale sensibility that marks a lot of Kim's solo works, even though Seth is a less propulsive writer, and his story of a guy working night shift at a lab and becoming convinced that the local dumpster rats are 'planning something' doesn't hang together with the same crackpot logic. The difference is palpable in Children of Aruf, wherein Kim only provides a lone full-page illustration, leaving Seth to meander through a selected tour of a world in which dogs can speak like humans. It's vaguely touching in the sheer empathy it brings to the subject, but Seth's language doesn't bring a lot to the telling.

No, the most striking stuff in here is surely courtesy of Kim Deitch alone. The shorter of the two, The Cop on the Beat, the Man in the Moon and Me, is Deitchian to the point of feeling like a yarn is being spun right in front of you with little concern for pace, perfectly willing to toss in an extended digression into big band and jazz musicians while recounting a typically beyond-plausible story of the artist's love of old cartoons and how it bumped into some of his experiences while working on comics in NYC in the '60s.

The Sunshine Girl is longer -- actually the longest story in the book -- and most perfectly Kim Deitch. It's a takeoff of Deitch's work as a cartoonist-journalist for Details (it was odd seeing an execution covered in his distinct style), in which he relays the story of a young woman who's intimately connected to the world of bottle cap collecting. Being a Deitch tale, just enough oddball truth is present to set the stage for a century-spanning opus centered around a counterculture entrepreneur's swingin' '60s plan to license Deitch's (actual) Sunshine Girl character from the East Village Other for a line of LSD-infused soft drinks inspired by the (actual) presence of cocaine in Coca-Cola for the first 15+ years of its existence, a calamity that has great repercussions on Our Narrator, who came of age amidst the crown cap scene of the early '90s, something about to explode into a commercial boom (hmmm, what's that like?) that belies the profound spiritual revelations that both ruined the girl's family and might yet provide for a lasting solace.

Collectors, madmen, marginal histories, forgotten distractions, profundity-through-jest: that's Kim Deitch, ace bullshit reporter no matter how he's filing his stories. I don't know how it'll look in coming years, but I'm glad it's still coming.

<< Home