And so, the weekend of manga concluded with a visit to the Doctor.

Dororo Vol. 1 (of 3)

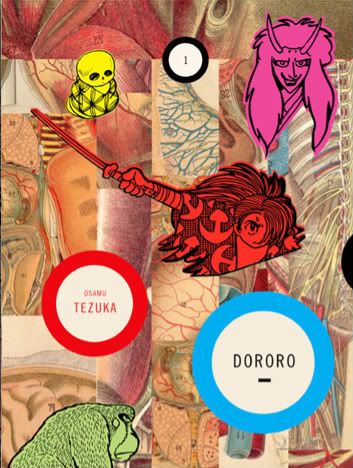

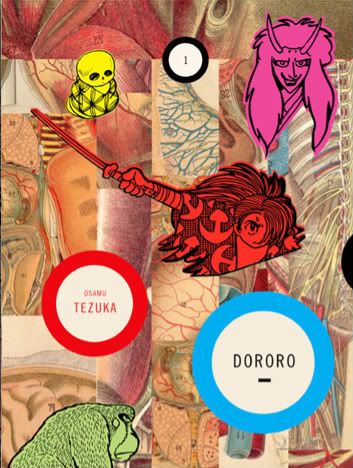

This should be out pretty soon. It's the new Osamu Tezuka release from Vertical, Inc., a right-to-left oriented softcover, 312 b&w pages for $13.95. It's doubtful you'll overlook Peter Mendelsund's cover design, which carries a certain charge beyond being merely striking - it's a new look for a new kind of Tezuka book, at least compared to what we've seen in English so far.

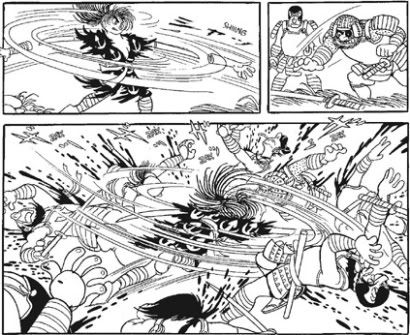

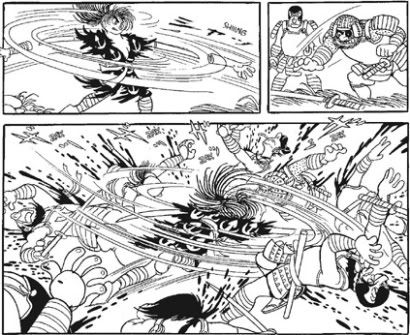

Simply put, Dororo is a straight-up action comic, stuffed from cover to cover with big fights, strange monsters, badass heroes, terrible villains, brooding atmosphere, swinging swords, gushing blood, black magic and bizarre phenomena. And that's not something Tezuka is typically known for in the West - Astro Boy might have its fights, but they're usually presented in a gentle-hearted, educational manner (oh when will humans and robots ever love?!), while the likes of Phoenix or Adolph are primarily concerned with philosophy or politics, or fine-tuned suspense mechanisms.

Not here. This is Tezuka's Hellboy, mixing occult politics, reimagined fables and two-fisted monster mashing into its saga of a monster/monster hunter hero, born into this world against his will and looking for somewhere to belong. It was a popular enough project during its initial 1967-68 run, although Tezuka never quite got around to giving it a firm ending. It was adapted to anime in 1969, and more recently spawned a 2004 Playstation 2 game (Blood Will Tell, featuring revised character designs by Hiroaki Samura of Blade of the Immortal) and a 2007 live-action film that's now going to be a trilogy - one might suspect this multimedia push did much to prod the manga's current release.

The story follows the adventures of teenage wanderer Hyakkimaru and his boy sidekick Dororo, as they make their way around a fantasy Japan in the midst of its extended Sengoku period of warring states. Poor Hyakkimaru has it hard from the start. His father, an ambitious Lord, cuts a deal with a horde of 48 demons: each will get one body part from the soon-to-be-born child in exchange for the diabolical power necessary to rule the land. The infant boy is thus born as little more than a human-like lump of flesh, and left to float in a basket, as a bastard, down a nearby river.

But as luck would have it, the bundle is found by The Most Magnificent Doctor in Japan, who discovers that the boy possesses mighty psychic powers and builds him an amazing prosthetic body so as to pass for normal. Seasoned Tezuka readers will note that this concept was recycled in the artist's later Black Jack series (the next Tezuka project Vertical will release!) as the origin story for the title character's own kid sidekick Pinoko, although she didn't have to deal with the shape-shifting spirits of the dead hounding her every step due to her haunted nature. Nor did Black Jack think to install hidden swords in her hollow arms or a "caustic water" hose in one leg - eat your heart out, Ogami Ittō!

Anyway, Hyakkimaru learns that by slaying the 48 demons he can get his lost body parts back, one by one, and he becomes a great fighter of legend who can use his innate superpowers to 'see' and 'hear' enough to hand out credible ass kickings. He also hooks up with Dororo, a child thief who'll fight anyone, tooth and fingernail, and their exploits are duly presented as they grow attached to one another while ending the lives of various entities.

A good deal of space in this volume is spent on both characters' origins -- according to Tezuka in English, Dororo was supposed to be a reader identification figure for the young audience, hence his name as the title, although everyone wound up liking the badass swordsman more -- but there's still time for clashes with a nasty frog monster that's won a village's trust, and a white-haired man who's possessed by the bloodlust of his cursed sword. And if Hyakkimaru seems more a 16th century Daredevil than Zatoichi the Blind Swordsman, rest assured that his luck is just as bad as your favorite Marvel characters of the late '60s - every adventure ends with him and Dororo getting unceremoniously booted out of town by an ungrateful populace.

All of this is accomplished via Tezuka's berserk entertainment aesthetic, which sees broad cartoon slapstick mingle with gory mayhem, comedy transforming into melodrama. Characters sometimes speak in modern slang, read manga, namedrop yōkai artist Shigeru Mizuki, and make reference to space aliens and cyborgs. Tezuka himself pops up on the page a few times, at one point getting his head cut off in the midst of an otherwise serious massacre sequence. Don't ask how Hyakkimaru's body is supposed to work, or how he can process visual information once he gets one of his real eyes back - a powerful trust is required between you and the characters! One delightful bit has Dororo receiving a psychic message, causing him to stare directly into the fourth wall and ask, "Was it you, reader?"

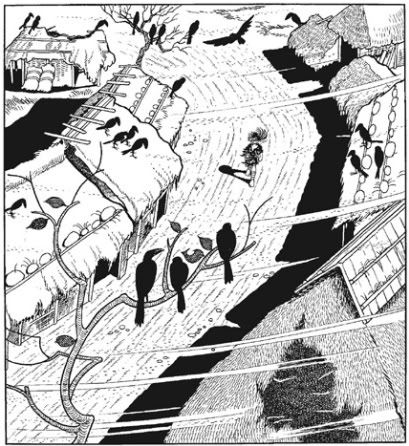

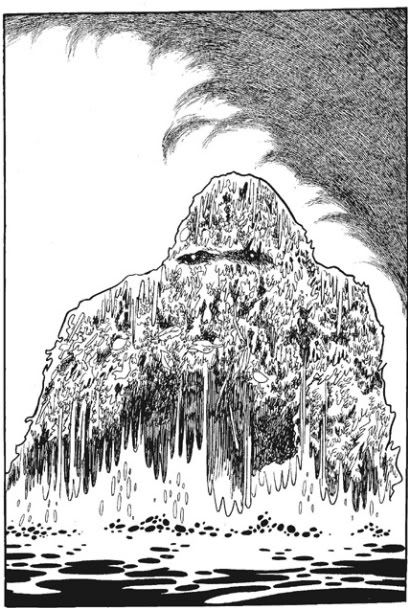

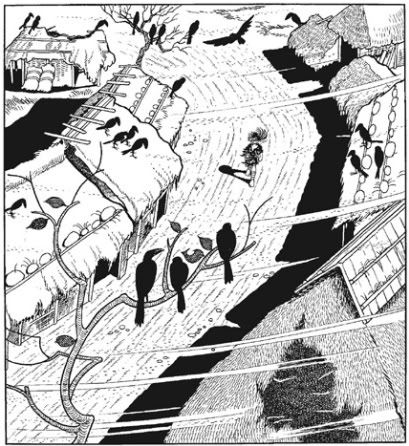

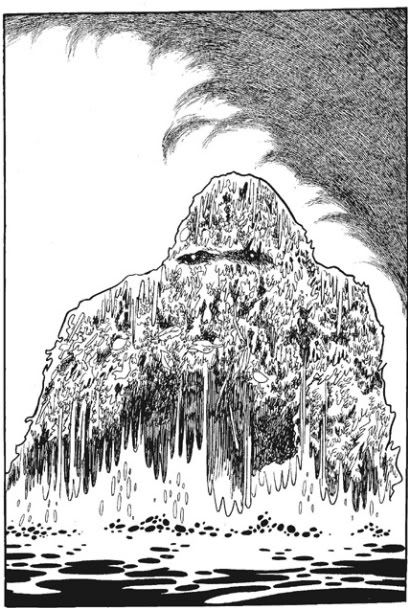

Perhaps because this approach plays out in the form of a horror-tinged action comic, Dororo ultimately feels like the most surreal thing we've seen of Tezuka's. The visual particulars are just as graceful as you'd expect from the Tezuka of the late '60s, sleek in design and swift in pacing, if not nearly as ambitious as they'd get in the older-skewing works of roughly the same time and thereafter (COM had just been founded in '67, for example), but the story's blend of mayhem and laffs and depression creates a uniquely chaotic world, one where Hyakkimaru can pop out his fake eyes as a joke, and duel with a pair of ghost sandals that spew geysers of blood when slashed. The monster designs are excellent, ranging from detailed etchings to gargantuan masses of doomy scribbles.

But in the end, for all its high/low spirits, Dororo is a dark work, one that suggests the effect of gekiga on even Tezuka's most youth-ready concepts. The cloud of war hangs over absolutely everything in these stories, from the circumstances that see both heroes left to wander the land as outcasts, to the demon that positions itself as rainmaker for a town ruined by battle. The cursed sword became addicted to blood after gorging itself on executions, and brings out the latent anger in all who hold it, because all are filled with hate at this world. People starve, resorting to cannibalism. When asked if this is what hell is like, a character replies "Hell's a lot better than this!"

Is it any wonder devils and monsters are roaming around? Tezuka may be patterning some of his stories after old tales, but his setting seems more the result of a man who came of age during a time of destructive militarism, and his struggles between samurai and peasants (do note that Hyakkimaru and Dororo come from opposite ends of the social order!) speak of the upheaval of '60s Japan. Sanpei Shirato's Marx-tinged ninja extravaganza The Legend of Kamui was still ongoing while Dororo was serialized, and though Tezuka's own sword-swinger isn't quite as political, his visions of ancient beasts and creatures from Hell find a most accommodating Japan to slither through.

But they can be killed.

Fitting for an action comic of this sort, the old Tezuka idealism creeps through in the realization that a man can be made whole by rolling up his sleeves, taking off his arms, and cutting through the cruelty of the world. His magic healing may undo the ambitions of the cold and powerful. We won't know, since the work is incomplete, but at least Tezuka's fables can offer some strange consolation, organ by organ through the nation's body populace.

This should be out pretty soon. It's the new Osamu Tezuka release from Vertical, Inc., a right-to-left oriented softcover, 312 b&w pages for $13.95. It's doubtful you'll overlook Peter Mendelsund's cover design, which carries a certain charge beyond being merely striking - it's a new look for a new kind of Tezuka book, at least compared to what we've seen in English so far.

Simply put, Dororo is a straight-up action comic, stuffed from cover to cover with big fights, strange monsters, badass heroes, terrible villains, brooding atmosphere, swinging swords, gushing blood, black magic and bizarre phenomena. And that's not something Tezuka is typically known for in the West - Astro Boy might have its fights, but they're usually presented in a gentle-hearted, educational manner (oh when will humans and robots ever love?!), while the likes of Phoenix or Adolph are primarily concerned with philosophy or politics, or fine-tuned suspense mechanisms.

Not here. This is Tezuka's Hellboy, mixing occult politics, reimagined fables and two-fisted monster mashing into its saga of a monster/monster hunter hero, born into this world against his will and looking for somewhere to belong. It was a popular enough project during its initial 1967-68 run, although Tezuka never quite got around to giving it a firm ending. It was adapted to anime in 1969, and more recently spawned a 2004 Playstation 2 game (Blood Will Tell, featuring revised character designs by Hiroaki Samura of Blade of the Immortal) and a 2007 live-action film that's now going to be a trilogy - one might suspect this multimedia push did much to prod the manga's current release.

The story follows the adventures of teenage wanderer Hyakkimaru and his boy sidekick Dororo, as they make their way around a fantasy Japan in the midst of its extended Sengoku period of warring states. Poor Hyakkimaru has it hard from the start. His father, an ambitious Lord, cuts a deal with a horde of 48 demons: each will get one body part from the soon-to-be-born child in exchange for the diabolical power necessary to rule the land. The infant boy is thus born as little more than a human-like lump of flesh, and left to float in a basket, as a bastard, down a nearby river.

But as luck would have it, the bundle is found by The Most Magnificent Doctor in Japan, who discovers that the boy possesses mighty psychic powers and builds him an amazing prosthetic body so as to pass for normal. Seasoned Tezuka readers will note that this concept was recycled in the artist's later Black Jack series (the next Tezuka project Vertical will release!) as the origin story for the title character's own kid sidekick Pinoko, although she didn't have to deal with the shape-shifting spirits of the dead hounding her every step due to her haunted nature. Nor did Black Jack think to install hidden swords in her hollow arms or a "caustic water" hose in one leg - eat your heart out, Ogami Ittō!

Anyway, Hyakkimaru learns that by slaying the 48 demons he can get his lost body parts back, one by one, and he becomes a great fighter of legend who can use his innate superpowers to 'see' and 'hear' enough to hand out credible ass kickings. He also hooks up with Dororo, a child thief who'll fight anyone, tooth and fingernail, and their exploits are duly presented as they grow attached to one another while ending the lives of various entities.

A good deal of space in this volume is spent on both characters' origins -- according to Tezuka in English, Dororo was supposed to be a reader identification figure for the young audience, hence his name as the title, although everyone wound up liking the badass swordsman more -- but there's still time for clashes with a nasty frog monster that's won a village's trust, and a white-haired man who's possessed by the bloodlust of his cursed sword. And if Hyakkimaru seems more a 16th century Daredevil than Zatoichi the Blind Swordsman, rest assured that his luck is just as bad as your favorite Marvel characters of the late '60s - every adventure ends with him and Dororo getting unceremoniously booted out of town by an ungrateful populace.

All of this is accomplished via Tezuka's berserk entertainment aesthetic, which sees broad cartoon slapstick mingle with gory mayhem, comedy transforming into melodrama. Characters sometimes speak in modern slang, read manga, namedrop yōkai artist Shigeru Mizuki, and make reference to space aliens and cyborgs. Tezuka himself pops up on the page a few times, at one point getting his head cut off in the midst of an otherwise serious massacre sequence. Don't ask how Hyakkimaru's body is supposed to work, or how he can process visual information once he gets one of his real eyes back - a powerful trust is required between you and the characters! One delightful bit has Dororo receiving a psychic message, causing him to stare directly into the fourth wall and ask, "Was it you, reader?"

Perhaps because this approach plays out in the form of a horror-tinged action comic, Dororo ultimately feels like the most surreal thing we've seen of Tezuka's. The visual particulars are just as graceful as you'd expect from the Tezuka of the late '60s, sleek in design and swift in pacing, if not nearly as ambitious as they'd get in the older-skewing works of roughly the same time and thereafter (COM had just been founded in '67, for example), but the story's blend of mayhem and laffs and depression creates a uniquely chaotic world, one where Hyakkimaru can pop out his fake eyes as a joke, and duel with a pair of ghost sandals that spew geysers of blood when slashed. The monster designs are excellent, ranging from detailed etchings to gargantuan masses of doomy scribbles.

But in the end, for all its high/low spirits, Dororo is a dark work, one that suggests the effect of gekiga on even Tezuka's most youth-ready concepts. The cloud of war hangs over absolutely everything in these stories, from the circumstances that see both heroes left to wander the land as outcasts, to the demon that positions itself as rainmaker for a town ruined by battle. The cursed sword became addicted to blood after gorging itself on executions, and brings out the latent anger in all who hold it, because all are filled with hate at this world. People starve, resorting to cannibalism. When asked if this is what hell is like, a character replies "Hell's a lot better than this!"

Is it any wonder devils and monsters are roaming around? Tezuka may be patterning some of his stories after old tales, but his setting seems more the result of a man who came of age during a time of destructive militarism, and his struggles between samurai and peasants (do note that Hyakkimaru and Dororo come from opposite ends of the social order!) speak of the upheaval of '60s Japan. Sanpei Shirato's Marx-tinged ninja extravaganza The Legend of Kamui was still ongoing while Dororo was serialized, and though Tezuka's own sword-swinger isn't quite as political, his visions of ancient beasts and creatures from Hell find a most accommodating Japan to slither through.

But they can be killed.

Fitting for an action comic of this sort, the old Tezuka idealism creeps through in the realization that a man can be made whole by rolling up his sleeves, taking off his arms, and cutting through the cruelty of the world. His magic healing may undo the ambitions of the cold and powerful. We won't know, since the work is incomplete, but at least Tezuka's fables can offer some strange consolation, organ by organ through the nation's body populace.

<< Home