Ay, there's the rub.

The complete Dream of the Rarebit Fiend by Winsor McCay

Of Winsor McCay's many comic strip creations, I know of only one that had a proper 'ending.'

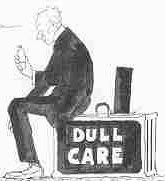

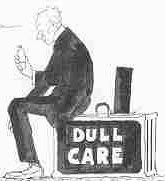

A Pilgrim's Progress, which began running in The New York Evening Telegram on June 26, 1905, concerned the misadventures of one Mr. Bunion, a fretful man in a top hat who's doomed to forever carry around a black valise labeled "DULL CARE," in evident (and likely Masonic) recognition of his worried internal state. Each episode saw him cook up another method for disposing of his hated burden - maybe burning it, or sinking it, or giving it away. But dull care ruled his life inside and out, and no allegorical confrontation or literary slapstick could save him.

It all came to a head on December 18, 1910, at which time Mr. Bunion adopted his most direct tactic: confronting his very creator, 'Silas' (the pen name used by McCay for his Telegram work of the time), and coercing him into not drawing the comic anymore. Nobody's dead cat came up in the ensuing conversation; indeed, most of the talking was done by Bunion, the character, flattering his author with praise for his hit-making ability while confiding that the strip's "laughter through tears" approach was flying over the heads of too many readers.

Silas eventually relented, although it was clear that Bunion could never actually lose the valise; he could only carry away from the eyes of the public. Bunion said his goodbye, urging Silas not to give in to "crude comedy" - the final panel saw him plodding off into inky blackness of cancellation, as Silas watched from the lighted portal to his office.

It's a bracing, funny and melancholic ending, wholly unpretentious yet disarmingly sophisticated, and deeply, almost dizzyingly self-aggrandizing. Reading it is revealing - about McCay himself, about his perception of his readership, about the editorial feedback he was probably getting, and about his affection for his creations as troubled souls. In a 1905 essay that ran in the Telegram, McCay denied being a funny man or a 'humorist' - he just couldn't keep comedic aspects out of his drawings of serious things, and thus his reportage became 'humor.'

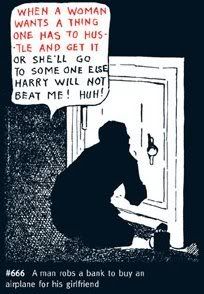

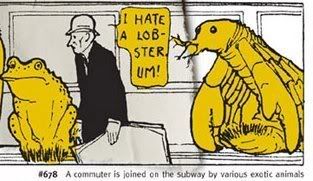

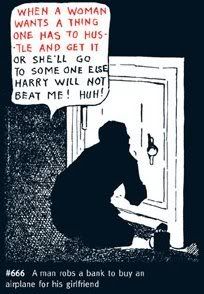

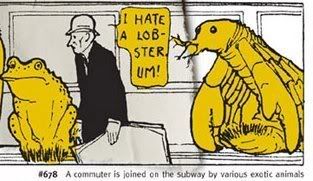

The essay, by the way, was all about the creation of McCay's longest-running strip, Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, which ran from 1904-13 in various papers in various forms, and even under various titles, with different foodstuffs called out as the potion of nightmares. Rarebit (as I'll now call it) is the one where each episode sees the world go mad on someone, only to have them wake up from their dream in the final panel and vow not to eat before bed again. It's also the subject of the book I'm reviewing today, and you might be wondering why I haven't mentioned much about it yet.

That's because my fascination with the book runs beyond the Rarebit strip itself, an inclination readily promoted by the tome.

Being the six-year labor of writer/editor/publisher Ulrich Merkl, a medieval illustration expert and art historian, The complete Dream of the Rarebit Fiend by Winsor McCay is a sprawling thing indeed. Hell, its very title goes through three variations before you're even into the text. It's 464 pages (144 in color), 17" x 12" in hardcover landscape format, and limited to 1000 copies only. It costs $133.00, after US shipping, and your best bet is to order it direct.

As the title indicates, it does collect all 821 Rarebit episodes known to exist, although be aware that the actual complete collection is on a dvd that comes included. This effectively shifts the burden of comprehensiveness away from the book itself, leaving it free to act as an idiosyncratic critical compilation of McCay themes and motifs, albeit one that happens to feature hundreds of full Rarebit episodes at their original publication size, in good (if somewhat variable) quality reproductions.

Indeed, its first 137 pages -- nearly 30% of the total -- are devoted wholly to analytic and explanatory material, much of it the result of Merkl's own study. He's very much inclined toward getting down the facts; unlike many other McCay compilations, this one presents a clean guide to exactly when and where the strips ran, and why they were running there. He also strives to detail McCay's career, highlighting all of his major creations (including the Bunion strip detailed up top; the final episode is included in its entirety), along with many of the bedeviling minor ones, all of them dressed in years of production, episode counts included. There's writings by McCay himself (including the essay I mentioned above), peeks at the inspirations behind the strip, comparisons to other works, and many large illustrations.

Even moving into the strips themselves, the mania for information continues. Everything is numbered, cross-referenced, and double-checked against prior strips. Constantly, images from other sources (comics, prose, film, etc.) are provided to compare with the Rarebit episodes, especially Little Nemo in Slumberland, which Merkl frequently posits as a design-heavy recipient of Rarebit ideas, devoid of the encyclopedic social concern of McCay's forays into adult dreams.

But Merkl doesn't just pay homage to an encyclopedia - he very nearly creates a complimentary one. Long stretches of those opening 137 pages are spent laying out McCay's favorite recurring motifs, and explicating on how they might relate to his life and his times. The book's design and production, by Andrea & Khaled Taha (collectively: Beduinzelt), blows countless panels and details up to giant size and garishly highlights important bits in yellow or red as Merkl's text cooly catalogs instances of, say, small men contrasting against large women, and wonders aloud as to the possible origins of such in McCay's marriage.

The approach as a whole can be exhausting, and may even prove distracting as to one's reading of the comics themselves. Certainly I felt a bit relieved when the spot color work stopped with the main presentation of the strips. Merkl's insistence on bringing up seemingly every possible thing McCay's work might have inspired across the whole of 20th century culture does get mildly silly, although some of it can be oddly persuasive. I do wish someone had cooked up a way to free the dvd from its case without ripping the back endpaper.

And yet, I do appreciate the character of the book, its one-man-show mania for achievement. Merkl does use other contributers -- Dr. Jeremy Taylor offers a long, fitfully interesting piece on the 'archetypal symbolic aspects' of the work, while Alfredo Castelli presents both a short critical essay on McCay's approach and a fascinating visual tour of prior and subsequent dream-focused comics from around the world -- but the work mainly beams with his own enthusiasm, however odd as it might get at times. Granted, many large books of comics come from small sources, like the Sunday Press Books line of deluxe reprints, but this one forgoes presentational distance for a paradoxically eccentric accounting that zips over, above, around, and sometimes through the work of its devotion.

I might have felt differently without that dvd - some might yet consider Merkl's work intrusive, and wish they'd just gotten all the cartoons in printed form. I enjoyed the book very much for what it truly behaves as: not a simple collection (that's the disc, although there's a big ol' Word document on there too), but a massively detailed person-to-person tour of one man's collection, with all the comments and asides one might expect from such an immersed host while showing off so many works in such fine form. And mark my words, with the cartoons themselves, Merkl does get the presentational basics down just right.

It's not just a major contribution to the availability of McCay's output to interested (if spendy) readers, but a work of gleeful, damn-the-torpedoes-this-is-my-book scholarship. Not all of it's compelling, but its many details have a way of sticking in your head, and you may find its side roads as intriguing as the main path. I can't just say 'give it a shot' at its price, but I do think McCay die-hards will find much to like.

Of Winsor McCay's many comic strip creations, I know of only one that had a proper 'ending.'

A Pilgrim's Progress, which began running in The New York Evening Telegram on June 26, 1905, concerned the misadventures of one Mr. Bunion, a fretful man in a top hat who's doomed to forever carry around a black valise labeled "DULL CARE," in evident (and likely Masonic) recognition of his worried internal state. Each episode saw him cook up another method for disposing of his hated burden - maybe burning it, or sinking it, or giving it away. But dull care ruled his life inside and out, and no allegorical confrontation or literary slapstick could save him.

It all came to a head on December 18, 1910, at which time Mr. Bunion adopted his most direct tactic: confronting his very creator, 'Silas' (the pen name used by McCay for his Telegram work of the time), and coercing him into not drawing the comic anymore. Nobody's dead cat came up in the ensuing conversation; indeed, most of the talking was done by Bunion, the character, flattering his author with praise for his hit-making ability while confiding that the strip's "laughter through tears" approach was flying over the heads of too many readers.

Silas eventually relented, although it was clear that Bunion could never actually lose the valise; he could only carry away from the eyes of the public. Bunion said his goodbye, urging Silas not to give in to "crude comedy" - the final panel saw him plodding off into inky blackness of cancellation, as Silas watched from the lighted portal to his office.

It's a bracing, funny and melancholic ending, wholly unpretentious yet disarmingly sophisticated, and deeply, almost dizzyingly self-aggrandizing. Reading it is revealing - about McCay himself, about his perception of his readership, about the editorial feedback he was probably getting, and about his affection for his creations as troubled souls. In a 1905 essay that ran in the Telegram, McCay denied being a funny man or a 'humorist' - he just couldn't keep comedic aspects out of his drawings of serious things, and thus his reportage became 'humor.'

The essay, by the way, was all about the creation of McCay's longest-running strip, Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, which ran from 1904-13 in various papers in various forms, and even under various titles, with different foodstuffs called out as the potion of nightmares. Rarebit (as I'll now call it) is the one where each episode sees the world go mad on someone, only to have them wake up from their dream in the final panel and vow not to eat before bed again. It's also the subject of the book I'm reviewing today, and you might be wondering why I haven't mentioned much about it yet.

That's because my fascination with the book runs beyond the Rarebit strip itself, an inclination readily promoted by the tome.

Being the six-year labor of writer/editor/publisher Ulrich Merkl, a medieval illustration expert and art historian, The complete Dream of the Rarebit Fiend by Winsor McCay is a sprawling thing indeed. Hell, its very title goes through three variations before you're even into the text. It's 464 pages (144 in color), 17" x 12" in hardcover landscape format, and limited to 1000 copies only. It costs $133.00, after US shipping, and your best bet is to order it direct.

As the title indicates, it does collect all 821 Rarebit episodes known to exist, although be aware that the actual complete collection is on a dvd that comes included. This effectively shifts the burden of comprehensiveness away from the book itself, leaving it free to act as an idiosyncratic critical compilation of McCay themes and motifs, albeit one that happens to feature hundreds of full Rarebit episodes at their original publication size, in good (if somewhat variable) quality reproductions.

Indeed, its first 137 pages -- nearly 30% of the total -- are devoted wholly to analytic and explanatory material, much of it the result of Merkl's own study. He's very much inclined toward getting down the facts; unlike many other McCay compilations, this one presents a clean guide to exactly when and where the strips ran, and why they were running there. He also strives to detail McCay's career, highlighting all of his major creations (including the Bunion strip detailed up top; the final episode is included in its entirety), along with many of the bedeviling minor ones, all of them dressed in years of production, episode counts included. There's writings by McCay himself (including the essay I mentioned above), peeks at the inspirations behind the strip, comparisons to other works, and many large illustrations.

Even moving into the strips themselves, the mania for information continues. Everything is numbered, cross-referenced, and double-checked against prior strips. Constantly, images from other sources (comics, prose, film, etc.) are provided to compare with the Rarebit episodes, especially Little Nemo in Slumberland, which Merkl frequently posits as a design-heavy recipient of Rarebit ideas, devoid of the encyclopedic social concern of McCay's forays into adult dreams.

But Merkl doesn't just pay homage to an encyclopedia - he very nearly creates a complimentary one. Long stretches of those opening 137 pages are spent laying out McCay's favorite recurring motifs, and explicating on how they might relate to his life and his times. The book's design and production, by Andrea & Khaled Taha (collectively: Beduinzelt), blows countless panels and details up to giant size and garishly highlights important bits in yellow or red as Merkl's text cooly catalogs instances of, say, small men contrasting against large women, and wonders aloud as to the possible origins of such in McCay's marriage.

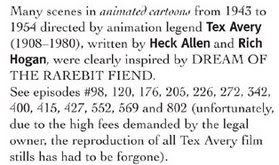

The approach as a whole can be exhausting, and may even prove distracting as to one's reading of the comics themselves. Certainly I felt a bit relieved when the spot color work stopped with the main presentation of the strips. Merkl's insistence on bringing up seemingly every possible thing McCay's work might have inspired across the whole of 20th century culture does get mildly silly, although some of it can be oddly persuasive. I do wish someone had cooked up a way to free the dvd from its case without ripping the back endpaper.

And yet, I do appreciate the character of the book, its one-man-show mania for achievement. Merkl does use other contributers -- Dr. Jeremy Taylor offers a long, fitfully interesting piece on the 'archetypal symbolic aspects' of the work, while Alfredo Castelli presents both a short critical essay on McCay's approach and a fascinating visual tour of prior and subsequent dream-focused comics from around the world -- but the work mainly beams with his own enthusiasm, however odd as it might get at times. Granted, many large books of comics come from small sources, like the Sunday Press Books line of deluxe reprints, but this one forgoes presentational distance for a paradoxically eccentric accounting that zips over, above, around, and sometimes through the work of its devotion.

I might have felt differently without that dvd - some might yet consider Merkl's work intrusive, and wish they'd just gotten all the cartoons in printed form. I enjoyed the book very much for what it truly behaves as: not a simple collection (that's the disc, although there's a big ol' Word document on there too), but a massively detailed person-to-person tour of one man's collection, with all the comments and asides one might expect from such an immersed host while showing off so many works in such fine form. And mark my words, with the cartoons themselves, Merkl does get the presentational basics down just right.

It's not just a major contribution to the availability of McCay's output to interested (if spendy) readers, but a work of gleeful, damn-the-torpedoes-this-is-my-book scholarship. Not all of it's compelling, but its many details have a way of sticking in your head, and you may find its side roads as intriguing as the main path. I can't just say 'give it a shot' at its price, but I do think McCay die-hards will find much to like.

<< Home