And now, for your hangover edification... the first good bookshelf comic of 2009!

Why I Killed Peter

That's right - what 2009 needs is a good stare down, and there's no better time than now.

This'll be out on Friday; it's a 112-page, $18.95 hardcover from NBM, bringing to English a 2006 work by writer Olivier Ka -- a prose specialist with various comics works to his credit -- and artist 'Alfred' (Lionel Papagelli), of various diverse comics projects (joined by Henri Meunier on colors). The two had previously collaborated on the 2003-04 humor series Monsieur Rouge, although I don't believe either have been published in North America before; this has proven to be their most acclaimed work, having enjoyed an Essentials designation (basically an 'honorable mention' prize) at the 2007 Angoulême International Comics Festival, along with Charles Burns' Black Hole and the final volume of the Emmanuel Guibert/Didier Lefèvre/Frédéric Lemercier comics & photography autobio-in-'80s-Afghanistan project The Photographer (forthcoming from First Second in an all-in-one edition).

Why I Killed Peter is also an autobiographical comic, and focused on subject matter that some readers will find upsetting - at the age of 12, Ka was sexually assaulted by an adult friend of his family, a priest who ran a summer camp the boy attended for several years before and after the incident. It was an isolated occurrence, and thus forms a core from which Ka urges foreshadowings and contexts and consequences to radiate, although this is not a particularly stream-of-consciousness work; its short chapters, direct past-present emotional correlations and recurring visual motifs suggest intense composure, even as Ka's story adopts so freewheeling a pose as to incorporate elements of its own creation into its later chapters.

No matter - the effect is consistantly that of a tightly-wound short story, to occasionally curt effect.

Ka begins his story at age 7, as he accompanies his grandparents to daily Mass; organized religion proves an ultimately boring experience, with the vivid side-effects of terror over Hell and anxiety over sex. It all stands in stark contrast to young Ka's life with his parents, a pair of free-loving suburban bohemians who think little of taking in strange folks in need, or letting the boy frolic ecstatically in a communal nude swim. And then there's Peter, the liberal priest who laughs broadly, wields a guitar and makes only endearingly sneaky attempts to foist religion on the kids.

Nothing remains the same for long, though - each new chapter begins with an image of Ka at an older age, and each year brings crucial changes, from liberated parents growing less fond of a 12-year old sharing a bathroom with naked women to the boy's own familiar mix of desire for girls and acute discomfort with his body. By the time Peter begins asking for a belly rub, there's no doubt as to how Ka's distaste for religion has gotten tangled with the priest as a 'good' authority figure, or how his genuine admiration for bodily freedom might affect his reception of Peter's demands, wrong as he knows they are, or how the isolated nature of the abuse could convince him that it's nothing to worry much about, just one of those awkward things - until the heavy psychological burden begins to buckle him, years later. The above jacket art ably illustrates how Peter (in red & white) becomes melded with the mental self (in telling, contorted black).

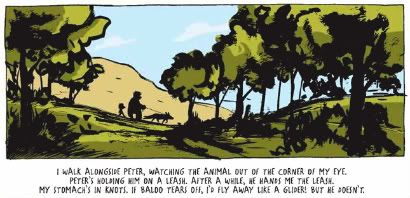

But Ka is perhaps too eager to provide such illustrations, to leave nothing in his recollection to chance. It's not enough to present the relative flaws of parents and grandparents - they must be discussed, in captions, atop an image of young Ka rending himself in two. The hazard of Peter's growing interest in the boy is bluntly foreshadowed by the presence of a scary dog that Peter lets Ka walk, as a special honor just for him, and while I certainly have no reason to doubt the presence of that dog at that time in this true story, its deployment in the book has only the character of a unsubtle literary device.

Moreover, these hammering clarifications are wed to a furious momentum. Nearly all of Ka's background provides some direct correlation of motive or understanding to something that occurs later, and while I understand the value of keying this entire life's story around a crucial focusing event -- not to mention the limited space with which Ka has to work -- the story's whole sometimes seems airless, and its telling thrust from one inevitability to another, which I think detracts from the writer's eventual confrontation of his pain as an adult, to 'kill' Peter.

It is fortunate, then, that Alfred is so versatile a collaborator. It's not just that he can switch from his 'default' style -- a bright, thick-outlined cartoon look prone to instances of emotional literalization, like a heart beating red in a chest or a happy man towering over a bus before an exciting trip -- to scratched, ink-smudged illness with ease, when the story's mood demands, but that he's so keen with navigating those deeper layers the visual component can add to a comic.

Sometimes it's a simple as drawing a panel of funny old folks as witnessed by Ka, age 7, and then drawing a scene-appropriate panel of similar composition to introduce us to a wedding reception attended by Ka, age 34, to suggest his arrival in the adulthood that once seemed so strange and gross. Or, with colorist Meunier, as seen just above, a character might suddenly spring to full, bursting hues as a means of popping out from faded, ossified look of Ka's grandparents, instantly identified as a departure from the religion of old, fearsome folks.

Yet Alfred's skill moves beyond even that, into the realm of bravura suggestion. He has a way of rendering natural scenes in thick gobs of brushed ink, lovely yet sinister at once. Nowhere is there more nature than at Peter's camp, of course. And when the awful night arrives -- to be fair, following some detailed, queasy dialogue setup by Ka -- the bodies of the boy and man are covered with similar splotches of ink, the blackness becoming more and more dominant as Ka offers short, frank bursts of words on what exactly is happening, until the whole scene is a deathly, abstract swirl, captions swarming and retreating as thoughts fly, punctuated by Meunier's most sickly colors as specific emotional jolts. It's absolutely harrowing material.

And then, after that, you really start to notice how Alfred's trees carry the same menace, and even quiet visions become soaked in latent threat, even if unacknowledged by Ka-on-page. One of Ka-the-writer's few moments untethered to some causation sees him at 15, still at Peter's camp, petting heavily with his first girlfriend. Peter sees them, and demands the girl return to her tent. But then he smiles at Ka and looks away, like a proud father, while the ashamed boy gets dressed before the black and hideous grass and trees, which are nevertheless also pretty and faded in calm colors. It is a truly haunting, powerful vignette, and a testament to all aspects of the form working in concert for meaningful conflict.

That's why this is a good comic -- some, I expect, will call it great -- in spite of my qualms. Even in as sensational a sequence as the adult Ka sprawled on a beach, shouting at inky images of characters (or versions of himself) from earlier in the book as they reiterate stances already made exceedingly clear, the visuals provide some added punch, tilting themselves slowly to one side so as to give the impression of the whole viewpoint slowly collapsing into a heap.

And do be aware that yes, the whole thing starts clicking together again as Ka turns 35, begins writing a book about his experience, recruits an artist he knows named Alfred, and heads off with his cohort to collect visual reference at the actual campground. Panels become digital photos of real scenery, until the pair arrive at the place, and discover what's still waiting. Conversing characters are then kept off-panel, as Alfred's nature scenes become what looks like digitally tinted photographs, two to a page, the caption-based narration sometimes dropping out altogether, as details begin to fade.

The ink vanishes; the trees become doodles. The colors are dabs of paint. Something is accomplished. Ka's story, so ferociously arranged to address its center event, can only stop; a final image freezes Ka's age, his many selves gathered together. The book is done. It's all out of him. It's something else. He killed it.

That's right - what 2009 needs is a good stare down, and there's no better time than now.

This'll be out on Friday; it's a 112-page, $18.95 hardcover from NBM, bringing to English a 2006 work by writer Olivier Ka -- a prose specialist with various comics works to his credit -- and artist 'Alfred' (Lionel Papagelli), of various diverse comics projects (joined by Henri Meunier on colors). The two had previously collaborated on the 2003-04 humor series Monsieur Rouge, although I don't believe either have been published in North America before; this has proven to be their most acclaimed work, having enjoyed an Essentials designation (basically an 'honorable mention' prize) at the 2007 Angoulême International Comics Festival, along with Charles Burns' Black Hole and the final volume of the Emmanuel Guibert/Didier Lefèvre/Frédéric Lemercier comics & photography autobio-in-'80s-Afghanistan project The Photographer (forthcoming from First Second in an all-in-one edition).

Why I Killed Peter is also an autobiographical comic, and focused on subject matter that some readers will find upsetting - at the age of 12, Ka was sexually assaulted by an adult friend of his family, a priest who ran a summer camp the boy attended for several years before and after the incident. It was an isolated occurrence, and thus forms a core from which Ka urges foreshadowings and contexts and consequences to radiate, although this is not a particularly stream-of-consciousness work; its short chapters, direct past-present emotional correlations and recurring visual motifs suggest intense composure, even as Ka's story adopts so freewheeling a pose as to incorporate elements of its own creation into its later chapters.

No matter - the effect is consistantly that of a tightly-wound short story, to occasionally curt effect.

Ka begins his story at age 7, as he accompanies his grandparents to daily Mass; organized religion proves an ultimately boring experience, with the vivid side-effects of terror over Hell and anxiety over sex. It all stands in stark contrast to young Ka's life with his parents, a pair of free-loving suburban bohemians who think little of taking in strange folks in need, or letting the boy frolic ecstatically in a communal nude swim. And then there's Peter, the liberal priest who laughs broadly, wields a guitar and makes only endearingly sneaky attempts to foist religion on the kids.

Nothing remains the same for long, though - each new chapter begins with an image of Ka at an older age, and each year brings crucial changes, from liberated parents growing less fond of a 12-year old sharing a bathroom with naked women to the boy's own familiar mix of desire for girls and acute discomfort with his body. By the time Peter begins asking for a belly rub, there's no doubt as to how Ka's distaste for religion has gotten tangled with the priest as a 'good' authority figure, or how his genuine admiration for bodily freedom might affect his reception of Peter's demands, wrong as he knows they are, or how the isolated nature of the abuse could convince him that it's nothing to worry much about, just one of those awkward things - until the heavy psychological burden begins to buckle him, years later. The above jacket art ably illustrates how Peter (in red & white) becomes melded with the mental self (in telling, contorted black).

But Ka is perhaps too eager to provide such illustrations, to leave nothing in his recollection to chance. It's not enough to present the relative flaws of parents and grandparents - they must be discussed, in captions, atop an image of young Ka rending himself in two. The hazard of Peter's growing interest in the boy is bluntly foreshadowed by the presence of a scary dog that Peter lets Ka walk, as a special honor just for him, and while I certainly have no reason to doubt the presence of that dog at that time in this true story, its deployment in the book has only the character of a unsubtle literary device.

Moreover, these hammering clarifications are wed to a furious momentum. Nearly all of Ka's background provides some direct correlation of motive or understanding to something that occurs later, and while I understand the value of keying this entire life's story around a crucial focusing event -- not to mention the limited space with which Ka has to work -- the story's whole sometimes seems airless, and its telling thrust from one inevitability to another, which I think detracts from the writer's eventual confrontation of his pain as an adult, to 'kill' Peter.

It is fortunate, then, that Alfred is so versatile a collaborator. It's not just that he can switch from his 'default' style -- a bright, thick-outlined cartoon look prone to instances of emotional literalization, like a heart beating red in a chest or a happy man towering over a bus before an exciting trip -- to scratched, ink-smudged illness with ease, when the story's mood demands, but that he's so keen with navigating those deeper layers the visual component can add to a comic.

Sometimes it's a simple as drawing a panel of funny old folks as witnessed by Ka, age 7, and then drawing a scene-appropriate panel of similar composition to introduce us to a wedding reception attended by Ka, age 34, to suggest his arrival in the adulthood that once seemed so strange and gross. Or, with colorist Meunier, as seen just above, a character might suddenly spring to full, bursting hues as a means of popping out from faded, ossified look of Ka's grandparents, instantly identified as a departure from the religion of old, fearsome folks.

Yet Alfred's skill moves beyond even that, into the realm of bravura suggestion. He has a way of rendering natural scenes in thick gobs of brushed ink, lovely yet sinister at once. Nowhere is there more nature than at Peter's camp, of course. And when the awful night arrives -- to be fair, following some detailed, queasy dialogue setup by Ka -- the bodies of the boy and man are covered with similar splotches of ink, the blackness becoming more and more dominant as Ka offers short, frank bursts of words on what exactly is happening, until the whole scene is a deathly, abstract swirl, captions swarming and retreating as thoughts fly, punctuated by Meunier's most sickly colors as specific emotional jolts. It's absolutely harrowing material.

And then, after that, you really start to notice how Alfred's trees carry the same menace, and even quiet visions become soaked in latent threat, even if unacknowledged by Ka-on-page. One of Ka-the-writer's few moments untethered to some causation sees him at 15, still at Peter's camp, petting heavily with his first girlfriend. Peter sees them, and demands the girl return to her tent. But then he smiles at Ka and looks away, like a proud father, while the ashamed boy gets dressed before the black and hideous grass and trees, which are nevertheless also pretty and faded in calm colors. It is a truly haunting, powerful vignette, and a testament to all aspects of the form working in concert for meaningful conflict.

That's why this is a good comic -- some, I expect, will call it great -- in spite of my qualms. Even in as sensational a sequence as the adult Ka sprawled on a beach, shouting at inky images of characters (or versions of himself) from earlier in the book as they reiterate stances already made exceedingly clear, the visuals provide some added punch, tilting themselves slowly to one side so as to give the impression of the whole viewpoint slowly collapsing into a heap.

And do be aware that yes, the whole thing starts clicking together again as Ka turns 35, begins writing a book about his experience, recruits an artist he knows named Alfred, and heads off with his cohort to collect visual reference at the actual campground. Panels become digital photos of real scenery, until the pair arrive at the place, and discover what's still waiting. Conversing characters are then kept off-panel, as Alfred's nature scenes become what looks like digitally tinted photographs, two to a page, the caption-based narration sometimes dropping out altogether, as details begin to fade.

The ink vanishes; the trees become doodles. The colors are dabs of paint. Something is accomplished. Ka's story, so ferociously arranged to address its center event, can only stop; a final image freezes Ka's age, his many selves gathered together. The book is done. It's all out of him. It's something else. He killed it.

<< Home